Phil Illy is an autogynephile. That is, he is a straight man who is attracted to the idea of himself as a woman. He attended the recent Genspect conference1 in a blue velvet dress and long blue gloves. The outfit, including its blueness, was striking. It was difficult to ignore. Sure enough, it was not ignored. There has been fury on-line and off about his presence at the conference.

The rad fems (and many others) say: Absolutely no. No way. A man—and clearly a creep, at that!—being celebrated in a space that already holds people with deep trauma from exactly this sort of cosplay? Reprehensible. This is damaging to those who are most at risk. Why are we encouraging this public display of fetish?

People in the other camp argue: Phil Illy knows that he is a man, and is in no way confused about this. He is honest and open, and not a creep at all. He has written a whole book about autogynephilia (AGP). We should be a big tent, welcoming of all, or at least, welcoming of those who are self-reflective, and who see the same reality that we do.

Which is it? Who is right?

The night before the conference began, many of us were in the vicinity of the hotel bar, and I saw a man walking around in a dress. I would later learn that this was Phil. I did a double-take. I asked the woman sitting next to me—am I seeing this correctly? She looked, nodded. Yep. I was unnerved. What did I not know? Did this person believe himself to be a woman, or not? Why did the answer to that question matter to me?

The next night Phil approached my table, offered me a copy of his book, which I accepted, and we talked for a bit. I came away with some answers and intuitions: No, he does not think that he is actually a woman. And no, he does not seem like a creep. None of my hackles were raised. I detected no malice, no glint in the eye, no smirk, outer or inner, that he was having one over on all of us. Of course I could be wrong about these things, as anyone’s intuition can mislead them. One of the despicable truths about gender ideology is that women are being told to stop trusting the very intuitions that we have always relied on, when walking alone, when entering a bathroom or a locker room or a parking garage, when approached by a person we do not know. It is not bigoted to cross the street if you feel a tingle at the base of your skull as you see a man approaching you. It is smart. I have traveled far and wide, often exploring places alone that women are expected not to explore alone, and I have honed my intuition, although I am well aware that I can and do make mistakes. Nothing about Phil alarmed me.

Assuming that I am correct about Phil—that he is not a creep, and that his intention is not to force himself into women’s spaces—is that sufficient to land me in the camp of the big tenters?

It is not.

Public Service Announcement:

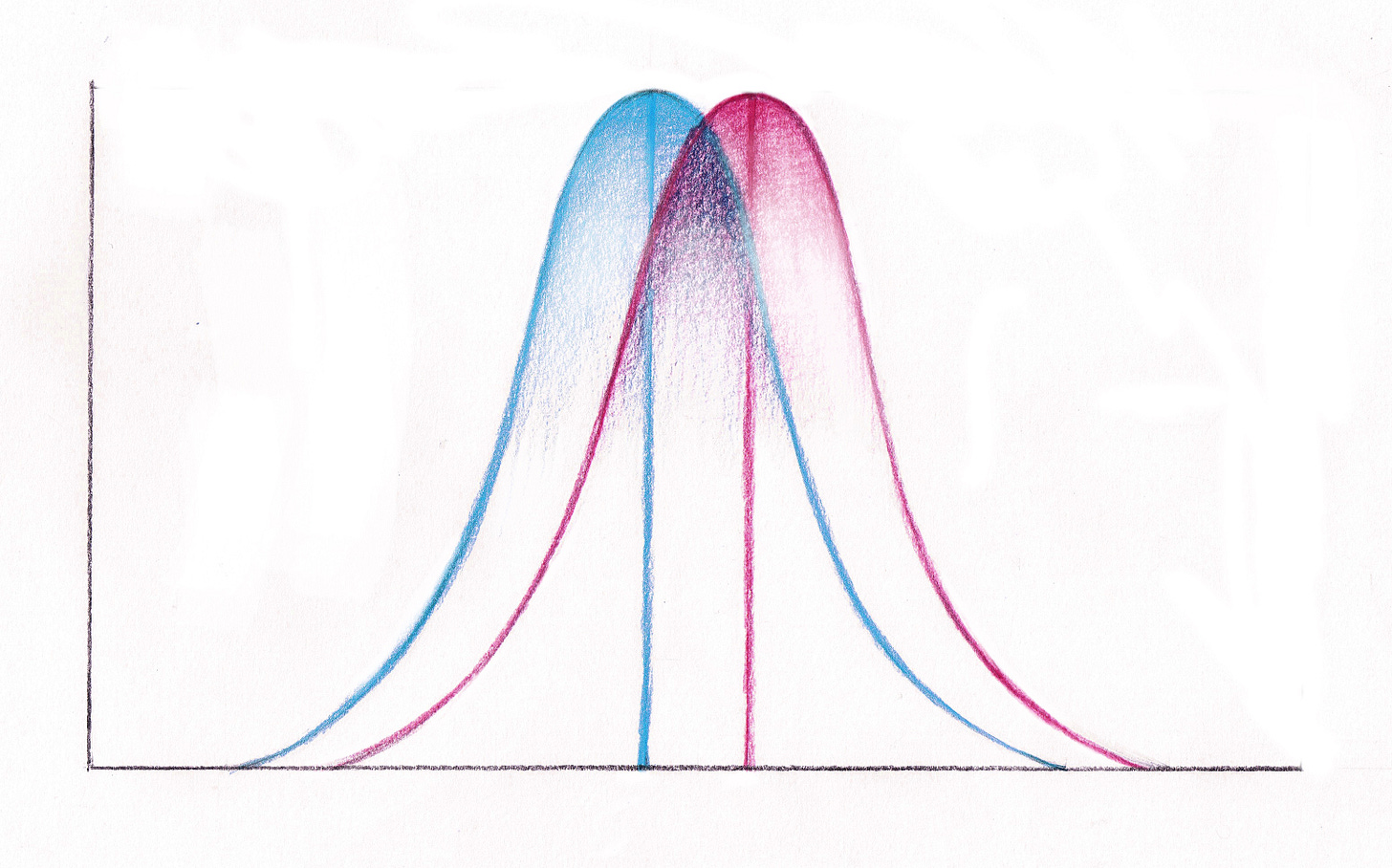

Sex is binary. Male and female exist not as points on a continuum, but as discrete states. Males produce small, motile gametes (sperm, or pollen if you’re a plant which, if you are reading this, you are not). Females produce large, sessile gametes (eggs)2.

Gender, which in other organisms we call “sex role,” is not binary. Gender is downstream of sex, and does manifest on a continuum. Gender is the software of sex3. In humans, because we are more software than any other organism on the planet, gender is particularly flexible, both across and within individuals.

We are fated to be the sex that we are born as. We cannot change that.

We can change how we behave, though. Our gender, aka our sex role—that is something that we have considerable dominion over.

Illy’s book is long—nearly 600 pages, plus another nearly 100 pages of end matter—glossary and references, mostly. I have merely skimmed it.

In his book, Illy attempts a careful, scholarly investigation of the condition that he understands himself to have—again, autogynephilia (AGP). I respect him for this. And his hypothesis—that AGP is the underlying cause for a large percentage of the people we now see transitioning—seems plausible, at least for young men. He has taken heat from the trans community for holding this position. But an unstated premise of the book is that what goes on in people’s heads is inherently something that the external world must pay heed to. This I do not accept.

Illy discusses not just AGP, but what he sees as its match in the opposite sex, autoandrophilia (AAP). AAP is the state of being a straight woman who has turned the object of her attraction inwards, and so is attracted to the idea of being a man. This, I believe, is a false symmetry. Just as male and female homosexuality are not identical, and typically neither emerge from nor manifest in similar ways, so too should we not expect confusion about gender identity to manifest similarly between the sexes. We are, after all, different.

I am a straight woman who has never thought nor wished that I was a man, but who has been gender non-conforming in many ways throughout my life. Opening Illy’s book to his section on autoandrophilia, therefore, may have been setting myself up for disappointment.

On p127 of Auto-Heterosexual: Attracted to Being the Other Sex, Illy writes:

“Autoandrophilia enables people to experience mental shifts into a masculine headspace in response to stimuli that reinforce their sense of masculinity or manhood….Initially, autoandrophilic mental shifts tend to be short-lived. They often first arise through crossdressing, being “one of the guys,” or imagining being a boy—all of which may lead to feeling confident, strong, or self-assured.”

The first part of this sounds like psycho-babble to me. The latter part sounds regressive and misogynistic.

I feel confident, strong, and self-assured. In fact, I am confident, strong, and self-assured. Hearing that feeling that way means that I may be thinking of myself as a man is neither helpful nor empowering. It is the opposite.

Earlier in the book, we are told that men who “behave like women” (“behavioral autogynephilia”) can benefit women who share spaces with these men. One man who calls himself a transfem says: “I treat my wife very well, because I take care of almost all the housework.” He does the housework because he sees himself as behaving like a woman. We are further told that “as a child another transfem delighted in caring for her baby sister, which eased the burden on her mother” (p96). Again, childcare was enjoyable for this boy because by engaging in it he felt that he was behaving like a female.

So: if you are confident, strong, and self-assured, you are manifesting manhood. And if you engage in care-taking and domestic work, you are manifesting womanhood. Manly men don’t clean. Womanly women aren’t confident. Manly men don’t parent. Womanly women are weak.

This is bollocks. I rather thought that we were over such insipid and restrictive tropes. Clearly, I was wrong.

Earlier yet in the book, Illy describes more ways that autogynephilia manifests, quoting a Hungarian physician from 130 years ago (pp 71-73). The physician—a man—“feel[s] like a woman in a man’s form…feel[s] the penis as clitoris…the scrotum as labia majora.” Beyond the delusions that his body is not what it is, the physician had “a sensory shift which made her feel as though she had the senses and perceptions of a woman.” Already, I admit, I am on alert. Men and women are likely, on average, to have differences in sensory and perceptive capacities. But having perceptions that are more typical of one sex or the other does not make you that sex. Those perceptions just make you a bit—or a lot—outside of the norm for the sex that you are. “Outside of the norm” and “belonging to a different category” are not the same thing.

Again: sex is binary. But everything that we might attribute to gender, to sex role—how we think and behave, how we remember things and what we like to do, our abilities and our interests—none of this is binary. Men are, on average, taller than women, but short men aren’t women. Men are, on average, more interested in math than women, but female mathematicians aren’t men.

Listening in on the thoughts of this male doctor from the late 19th century reveals how much of his delusion is based on cultural norms:

“Her stomach rebelled against every deviation from a ‘female diet.’…Her skin felt feminine; it had become sensitive to both hot and cold temperatures, as well as direct sunlight. She resented social norms that kept her from using sun parasols to protect her sensitive face skin and took to wearing gloves as much as possible, even while sleeping.”

I don’t have any reason to doubt that the physician felt the way that is being described, even if I don’t understand what some of it means. What I disagree with is the stereotyping of men and women, the normalization of mental confusion, and the religious conclusions thinly veiled as scientific ones. At Genspect and elsewhere, I have discussed some of the scientific findings that male and female brains are, in some regards, on average, different. This is true. It is replicable using modern scientific tools. And it is irritating to some people. Too bad, though: reality is not always what you want it to be.

However. Having autogynephilia, we are told on p69, “can feel like having a female soul.” This, in contrast to a scientific hypothesis, is an unfalsifiable claim. It is untestable, and reveals the religious nature of the belief. I am not opposed to religion. But I insist that your religious beliefs not infringe on my (secular) freedoms.

Name a thing, and it becomes real—this is the postmodernist thinking behind many modern arguments. Once the thing is made real by its name, it comes to seem ever more true. And voila, the slippery naturalistic fallacy is manifest: name X, point to the reality of X on the basis of its name, conflate X’s reality with its inexorability and its goodness, and in turn, force the acceptance of X.

There is plenty that is real that we need not accept, indeed, that we must not accept. Consider rape. Rape is an evolutionary strategy. Understanding its evolutionary origins will help us decrease its prevalence. We want to decrease its prevalence because it is deplorable. Similarly: slavery, genocide, and all of the rest of the totalitarian tendencies that spread through populations. These are evolved strategies that we can, in part, understand with an evolutionary toolkit. And as nobody but those inflicting such barbaric acts on others benefit from them, we should try to eradicate them. Understanding is not accepting. Sometimes, understanding is in service of the exact opposite.

Understanding fetishes like autogynephilia is, I would argue, just such a thing. By rejecting the fetish, we are not rejecting the human being who has it, but we are rejecting its public display. Again: understanding is not the same as accepting.

I will no doubt be accused of thinking that anything non-heterosexual or reproductive is a fetish. Will be accused of being “vanilla,” even. Here’s the thing: No. Humans have long since evolved into beings who have sex and engage in sexual behavior for non-reproductive purposes. Many of our closest relatives do as well (see bonobos). Just as food for us is about more than nutrition, so too is sex about more than reproduction. We are so social, so tightly bound to one another, that we have elaborate feasts that go on hours—days even—when we could have gotten the benefit of the calories and nutrients in a few minutes. So, too, do we have sex that extends far past the boundaries of what is necessary to make a baby. We play games, create fictional scenarios, engage in fantasy. This is not just evolutionary (which again, does not mean that it is good). In the case of our expansive sexual appetites and repertoires, though, they are not just evolutionary, but also, often, good for individual humans. But not always.

Not everything that has evolved is good. Nor does it follow that anything that people currently believe, no matter how much of a community they have found on-line, or how many university professors have written scholarly articles about the phenomenon, is either evolutionarily robust, or good. We live in an era of hyper-novelty. The rate of change that we ourselves have created has out-stripped even our capacious ability to keep up with it. And so, when assessing any bit of 21st century behavior—or indeed, much of what emerged in the 20th century—it is necessary to keep an eye on that truth: just because many people are doing it, does not mean that it is the right thing to be doing.

We are under no obligation to normalize such feelings. Indeed, we are obligated to do the opposite. We do not cheer for the self-mutilation of a sad girl, or for her attempts to starve herself. We do not celebrate confusion.

Normalizing fetishes and other rare mental states is bad for society, because it provides a template for the confused. The internet, we are told, has been a boon for people who did not know that anyone else in the world felt like they do. The internet helped gay children in fundamentalist communities, neurodiverse kids in small towns, artistic types born to families that favor money over creativity, to find their people. The flip side of this, which affects far more people, is that once niche identities become named and organized on-line, anyone can find them. And then, young people searching for meaning—or more often now, searching for identity, a weaker tea by far—come across something they did not know existed, and if any of it fits, they think: ah yes, this has been me all along.

It is our job as adults—as parents, as teachers, as health professionals, and just as responsible members of society—to protect the children. Providing them a menu of fetishes to choose from, to identify as, is not protecting them.

In Me, She, He, They: Reality vs Identity in the 21st Century, I wrote:

We are dealing with the interface between long standing products of evolution, subtle matters of humanity which have blurry borders, and a brave new world of technological modifications that has yet to stand any test of time. That leaves all of us, even those who are thoroughly versed in the facts and logic of sex and sexuality grappling with new and genuinely difficult questions. No one has yet worked out the solutions that best resolve all of the tensions.

Genspect is doing necessary work, navigating perilous waters and welcoming diverse people and views. They expect adults to come to their own conclusions. Running a conference on non-fraught topics isn’t easy; literal gate-keeping on a topic so explosive has to be nearly impossible. I was honored to be a speaker at their conference, and see them, unflinchingly, as a force for good.

What of Phil Illy4, though? He was an attendee of the conference, is a man who understands what he is, is exploring it both in a scholarly fashion and a human one, and is also displaying the fetish for all.

Even if it is true that any particular man will not behave in a predatory way to women, the public display of fetish opens up doors to predators who would. We had a social contract that did a good job of keeping women safe. Public display of fetish begins to dismantle that contract.

The fact that Phil is not himself a creep thus does not render his behavior harmless. He is breaching a social contract by walking around in hyper-feminine garb, causing people’s brains to throw errors and—for women—to become hyper-vigilant about what it means and how to react. The indirect effects of a man—even a good man—walking around in stereotypically female dress, in an era when other men who do this expect to be allowed in to female only spaces, to be treated as if they are women—are negative. I suppose that this is too bad for Illy, and others like him, that they should be expected to curtail their behavior because of other bad actors. But it is far worse if he does not curtail his behavior in public, far worse for the 50% of the population who are now on high alert at all times, protecting ourselves and our children against the compulsions of a few.

Genspect envisions a world in which “people are free to present and express themselves in a manner that is healthy, safe and not constrained by gender stereotypes.” The Genspect conference was excellent, as is the organization in general. I wrote about the conference some in last week’s post, here. Genspect took a metaphorical beating after, in the wake of the conference, they tweeted positively about Illy and his new book; they have since deleted the tweet and offered up this post. The on-line dust-up was ugly, angry, and raw, as too many are. Ultimately, what happened was mostly friendly fire; the casualties, such as they were, were largely unnecessary.

More precisely, although the precision is only really necessary when engaging sophists, females are individuals who do or did or will or would, but for developmental or genetic anomalies, produce eggs. Here is where I have written about what a woman is the most concisely.

Bret Weinstein and I discuss this in the “Sex and Gender” chapter of A Hunter-Gatherer’s Guide to the 21st Century.

Illy has been on Benjamin Boyce’s podcast twice. The conversations are interesting.

"They should be expected to curtail their [public] behavior" is a large part of what is missing from society today. Once upon a time, we knew that there are behaviors that belong only to the private, not the public sphere -- not only fringe behaviors, but also those that are natural and essential (e.g. defecation), and those that are good and honorable (e.g. those that, in the right circumstances, lead to the creation of children and families). This loss of a sense of privacy -- call it by the old-fashioned term, modesty -- is destructive of both individuals and society. That those to whom we have traditionally entrusted our children (e.g. teachers, librarians) are now on the forefront of the movement to expose even the youngest to everything they once protected them from, is unspeakably tragic.

Why does a private fetish need to be public? Do you need that much attention.