Welcome to the Age of Censorship.

Fact-checking organizations are hanging out shingles at every on-line corner, celebrating their own awesomeness with fact-checking festivals, while fact-checking into oblivion true things that are awkward for the powers-that-be1. Universities are making up lists of Very Bad Words—words and phrases like blacklisted and insane and walk-in office hours—which should not be used anymore. Big tech is shutting down and demonetizing people and platforms that speak inconvenient truths, from Twitter to YouTube.

Even governments have gotten in on the act. In the U.K., the “Prevent” program has helpfully identified possible right-wing threats. Those nasty purveyors of wrongthink include but are by no means restricted to Douglas Murray, George Orwell, and the long-running BBC documentary series Great British Railway Journeys. In the U.S, things seem comparatively sane. The Department of Homeland Security has merely issued endless National Terrorism Advisory Bulletins, citing mis-, dis- and mal- information as central to their concerns, and created an admittedly short-lived “Disinformation Governance Board,” with an accomplished purveyor of disinformation heading it up.

And then there are the sensitivity readers. Surely this is a category that Orwell would have been proud to include in Newspeak. Given that war is peace, and ignorance is strength, perhaps censorship is inclusion. Or maybe censorship is enlightenment.

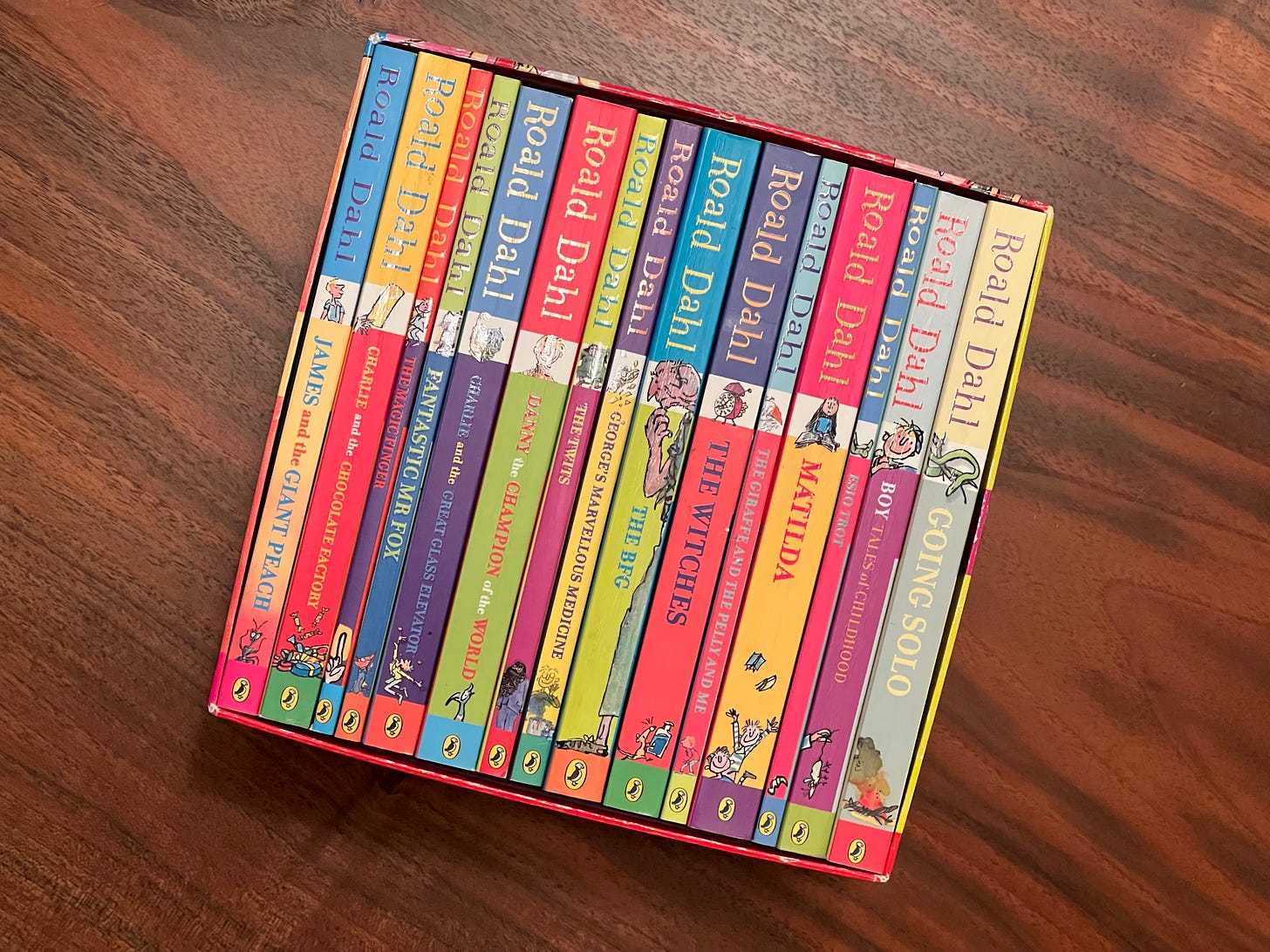

Censorious sensitivity readers have been invited to destroy all manner of good things, including most recently the works of Roald Dahl. Dahl (1916 – 1990) was a prolific and immensely popular 20th century author whose most famous works were written for children: Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, James and the Giant Peach, Fantastic Mr. Fox, among so many more. In a remarkable and exhaustive article, journalists at The Telegraph have revealed a staggering array of changes made to Dahl’s work by sensitivity readers.

Many of the changes are of a type. For instance, more than a dozen instances of the word “white” were changed. White was changed to pale, frail, agog or sweaty, or else removed entirely. Because, you know, a color can be racist.

In one book alone—The Witches—The Telegraph counted 59 new changes. These run from the banal—”chambermaid” is replaced with “cleaner”—to cleansings that appeal more directly to modern pseudo-liberal sensitivities. The suggestion that a character go on a diet, for instance, is simply disappeared. And this passage:

“Even if she is working as a cashier in a supermarket or typing letters for a businessman.”

Has been changed to:

“Even if she is working as a top scientist or running a business.”

It’s hard to know what even is believed by the censors who made these changes. Do they mean to suggest that nobody should go on a diet, or that no woman has ever worked as a cashier or a typist? And what, pray tell, is a “top scientist.” I’m guessing that none of the censors could provide a working definition of science, but that when asked to conjure a scientist up, they imagine someone with super science-y accoutrements, like a white lab coat and machines that whirr in the background. Sorry, that would be a pale lab coat.

The censors seem to believe that we moderns have perfect insight into what is good and right, and that we now live on a pure spiritual plane. Only people of the past made errors, had secrets, and believed things that weren’t true.

What the censors are revealing is how very many errors it is possible to make at a single moment in time. We are, it seems, a confused and arrogant people.

Allow me a diversion into my own educational history, and what I learned from my students, many of whom, by the time I met them in college, had had a wildly different experience than mine in school.

I was one of the lucky ones: I loved school, I was good at it, and I learned from it. One or more of those conditions is missing for most people, sometimes causally so: If you can’t learn from school, you’re probably not good it, and you definitely don’t love it. And being “good at school” may mean that you love it, because you’re getting rewarded there, but that doesn’t inherently mean that you’re learning.

It is one of the great failures of modern education that most educators are either people like me in this regard, or people who were good at school without being good at learning in school. Both look like “A-students” from the outside, but we’re not really the same. It is a failure of modern education that the adults who choose to make a life there mostly come from the ranks of A-students, because many A-students can’t grasp that people who don’t get good grades are not inherently stupid or lazy.

If you’re a human of any age, and have not compelled yourself into a fury of denial stemming from ideological certainty, you will know this: kindness can show up in the most unexpected places. So too insight. And wisdom.

The fact is that some of us are better analysts than others, while others are better at creating social environments that facilitate connection. Some of us may not want to look you in the eye, but still want to interact; others of us can’t do math, but know that it’s necessary, and would rather not be lied to with it. Some of us are always moving our bodies (or want to be); others are quite happy to sit still, calmly and quietly, while others speak for hours on end.

Given the great variety of ways that we experience the world, and given that school is inherently less diverse in its manifestation than are the students who populate it, it should be obvious that many people will not be a good fit for school. This does not mean that they are stupid. And it does not mean that they are lazy. There are surely both stupid and lazy people among those who are not good at school. As, I know for a fact, are there stupid and lazy people among those who are good at school.

“What?!” you may cry, outraged at the insult from another A-student such as yourself. “We are nothing if not smart!” Many of us are, yes. I will even go so far as to say that there will be a higher proportion of smart people among the A-students than there are among the C-students. But there are many brilliant people among the C-students, and many who are not brilliant among those who earn better grades. It is quite possible to be “good at school” without being good at just about anything else: learning to game the system, while no doubt useful, is not a strong mark of intelligence.

I hazard to guess that modern day censors—the sensitivity readers of Roald Dahl, the university Newspeakers, the fact checkers of PolitiFact—were mostly A-students. What comes next is based on that assumption.

Maybe those A-students got there the honorable way, happening to be well-suited to school-style learning, loving the process, and learning voraciously along their entire academic path. Or maybe they got there by learning how to game the system, memorize some stuff, and regurgitate back to teacher what teacher most liked to hear2. I’m thinking there is a mix of these types among the censors. But if the censors are mostly or entirely made up of A-students, there is a good chance that few if any among them actually have empathy for those who weren’t or aren’t good in school. The censors are bullying others in mental space, just as schoolyard bullies do so in the physical3.

What about the children who don’t do well in school, but are full of wonder? There are millions of these right now, and many more to come. What about the children who won’t sit still, can’t stand quiet time in class, spend more time looking out the window than at the board? What if many of them, when back home, freed from the strictures of school, find something to adore in the words of Roald Dahl? Or Laura Ingalls Wilder. Or C. S. Lewis. Or J. K. Rowling. And what if, in their adoration of the words of Roald Dahl, they have a chance of becoming educated?

Children who do fine in school may find other ways to learn about fiction and story, history and reality. Although frankly, that’s becoming ever more difficult too, given that some other large fraction of the “good students” are now populating the schools as teachers, applying their ideological wickedness directly to children. The luckiest among us, the most privileged, have houses already full of books, with the original text intact, and family and friends eager to read to children, to engage the ideas therein with both wonder and criticism. Fiction percolates.

But children who learn little if anything in school, and who do not have houses full of books to return home to, particularly need these books. They need the books as they were written, warts and all. The very people whom the censors claim to be working on behalf of—the under-served, the under-privileged, the historically oppressed—are precisely the ones whom censors are guaranteed to harm the most.

There are many things troubling about the creative work of an author being changed after his death. It interferes with our understanding of our own history. We live downstream of our actual history, which did not change just because censors got ahold of our documents. Having the recorded version of history scrubbed interferes with our ability to make sense of our world.

Post-mortem revisions are also bad for art. These edits raise questions of creative autonomy. Of voice. Of what fiction is for. Fiction is not mere entertainment. Fiction educates and uplifts, informing readers about ourselves and our world, and also about the moment in time that the work was created.

The Telegraph reports that Dahl wrote in Esio Trot (his final book, published in 1990, the year of his death) that tortoises were being brought into England, “mostly from North Africa.” The censors removed the original specificity, such that now the tortoises “came from lots of different countries.”

Putting aside the outrage that may boil up—what on earth did they change that for?—consider the effect. In the original, there was somewhere new that your brain could take you: oh, are tortoises mostly from North Africa? Or was it just these particular tortoises, and if so, is there something uniquely transportable about these particular tortoises? Or did the English have an historical relationship with pet traders in North Africa? Was it illegal at the time—the importing or the exporting? Legal but frowned upon? What kinds of lives did North African pet traders have?

Curious if there was any more detail in the original, I unearthed the boxed set of Roald Dahl’s books that I bought for my own children many years ago, and had long since carefully packed away to save for their children. In Esio Trot, I was amazed to find that this section struck by the censors wasn’t in the book itself: it’s in the Author’s Note. Dahl is providing a literal description of a reality that existed, which provided one of the germinating ideas for his book. The censors have even gone after and altered the Author’s Note to his readers.

The Telegraph further reports that in the original book, Dahl mentions a “bedouin tribesman,” but in the 2022 edition this is cleansed to “local person.” I suspect, but do not know, that all mention of Africa has been eradicated from the new publication. I suspect this in part because when I found the relevant passage in the original, I was actually shocked by what I found there:

“Mrs. Silver,” he said. “I do actually happen to know how to make tortoises grow faster, if that’s really what you want.”

“You do?” she cried. “Oh please tell me! Am I feeding him the wrong things?”

“I worked in North Africa once,” Mr. Hoppy said. “That’s where all the tortoises in England come from, and a bedouin tribesman told me the secret.”

“Tell me!” cried Mrs. Silver. “I beg you to tell me, Mr. Hoppy! I’ll be your slave for life!”

When he heard the words slave for life, a little shiver of excitement swept through Mr. Hoppy. “Wait there,” he said. “I’ll have to go in and write something down for you.”

My sensibilities are prickled by this. I am discomfited. I don’t like the idea of anyone offering to be a “slave for life,” nor do I like that someone who is supposedly attracted to that person would be eager to receive such a gift. I really don’t like it at all.

If I were reading this book to a child, this would be a learning opportunity. We could discuss metaphor, and the fact that language changes over time, and that phrases that may have been common in the past can be jarring in the present. And we could discuss the broader implications—why is this jarring now? Why wasn’t it then? Does that suggest a complacency about actual slavery, or something else?

Far better that than disappear what is currently viewed as ugly. That which is driven underground often becomes stronger while out of public view. Rather than pretend that such things don’t exist and never did, we need to have them on full display. This, in part, is the value of freedom of speech and expression. Let those with actually nasty views speak, so that we may hear them, and know who they are, and remember, and learn. Similarly, let views from the past that some will find ugly today be in the public eye, so that we may remember, and learn.

In every one of these censorious cases, there is loss. Loss of detail. Loss of story. Loss of language. Loss of the past, including loss of evidence of the bigotry of the past. How are we to make sense of our trajectory, and best plan a future, if our history is smudged, altered, and erased?

As I wrote here, PolitiFact has a highly technical 6-tiered rating system for their—wait for it—truth-o-meter. “Pants on fire!” is the lowest of the low, assigned only to the most awfully untrue things out there. In September of 2020, PolitiFact assigned a “pants on fire!” rating to the lab leak hypothesis for the origin of SARS-CoV2. While nothing changed in terms of the scientific evidence between then and May 2021, the political winds had shifted some, so PolitiFact quietly removed this fact-check from their database, saying that the claim is now understood to be “more widely disputed.”

Regurgitating expectations back to teachers doesn’t work so well on the best teachers, but most teachers, ipso facto, aren’t the best teachers.

We have gotten good, at a societal level, of shutting down physical bullies, both shaming and punishing their behavior such that it has become less prevalent, while simultaneously paving the way for emotional and mental bullies, those who do not inflict physical marks, but stand to destroy things far greater than a single individual with their tactics. This tendency—to shut down the physical version of a bad thing, while leaving the emotional/mental version of it intact—can be found across domains, and is roughly akin to a static rule that says: the typically masculine form of this behavior is always bad, while the typically feminine form of this behavior can be condoned, or even celebrated.

Personally, I couldn't care less if these petulant re-writers/art vandals love or hate Kipling, or want Oompa Loompa's to be transgender, or think "black" tractors is somehow a racist descriptor (they actually nixed that adjective from Fantastic Mr. Fox, fearing it might send the "wrong message")...

...but let these do-gooders write their own damned novels, if indeed they can!

As someone who has dedicated a good portion of the past few years to realizing his life-long dream of becoming a failed novelist, I can heartily attest to Thomas Mann's wry observation: "A writer is someone for whom the act of writing is more difficult than it is for other people."

Real writing is hard, in other words. Censoring the dead, meanwhile, is as simple-minded as it is cowardly. Putting words in the mouths of those who can no longer speak, and sullying their reputation with this bilious nonsense, seems to me the height of pretension. A pox on all their houses!

This is one of my favorite articles from NS. Your argument about “A-students” is well articulated.

This information about the censoring of past works is all the poignant as I just read 1984 by Orwell last month. It’s a page right out of the book. This whole story creeps me out. It’s one thing to edit websites or stories published online, but it feels like we are in a new realm when people start editing past works of art. Work that they didn’t create and have no claim over.