We live in a state that was hard hit by Covid-19: New Jersey. We also had heavy-handed measures mandated by our governor, Phil Murphy, who entered into a regional agreement—they called it a “collective state policy”—with governors Cuomo in New York, and Lamont in Connecticut. Governor Murphy called us knuckleheads, and told Tucker Carlson that knowledge of the Bill of Rights was above his pay grade. The logic behind the “collective state policy” seems to have been the bigger the stick, the more fear we would have in disobeying them. King Solomon teaches that “A cord of three strands is not easily broken.” That wisdom was borrowed in 2020 by the governors of my state and others, repurposed to keep the citizens of their triad in line.

We are a multi-generational household. When the pandemic began in 2020, four of our five grown children—three daughters and a son—plus a teenaged granddaughter, lived with my husband and me. Our fourth daughter lived 18 miles west with her husband, in their own house in a small village. She still does. There’s no need for me to explain how we got to where we are. We didn’t expect that our grown children and teen grandchild would be living with us, or that we would live during a pandemic ‘lock down’, but life often goes in directions unforeseen. We’re fortunate we have good, decent, and helpful children, and a home large enough to accommodate all of us comfortably.

Decades earlier, we had had four daughters in five years. Then there was an eight year gap before our son David was born. The girls were thrilled to have a brother, and we were equally happy to have girls and a boy to love, and experience their differences. Those years rushed by.

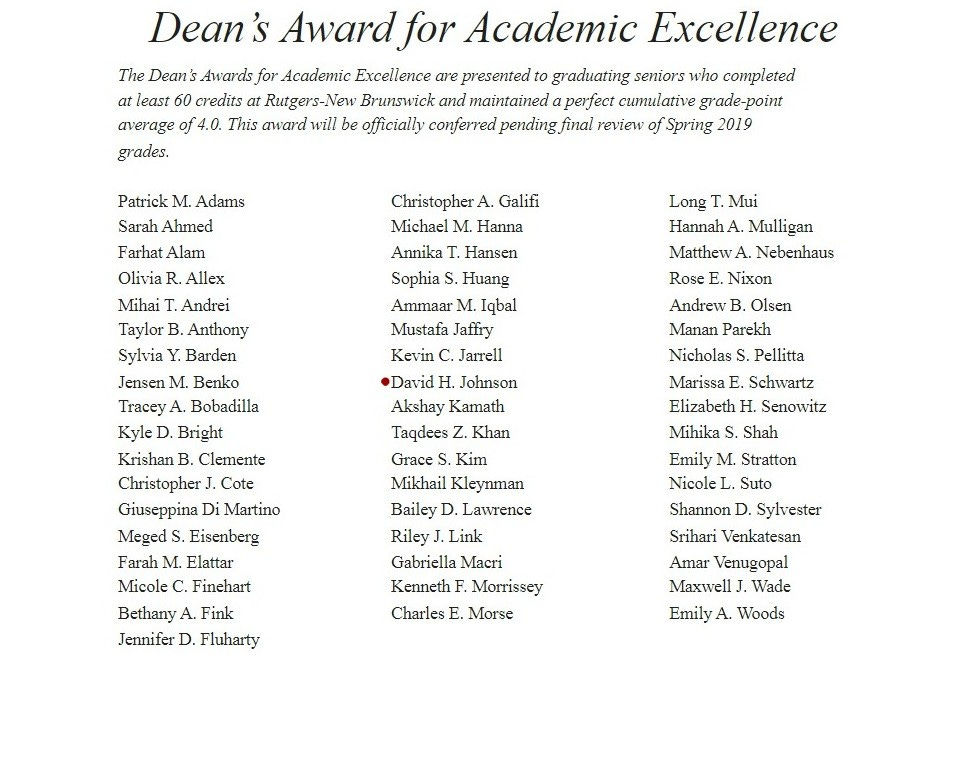

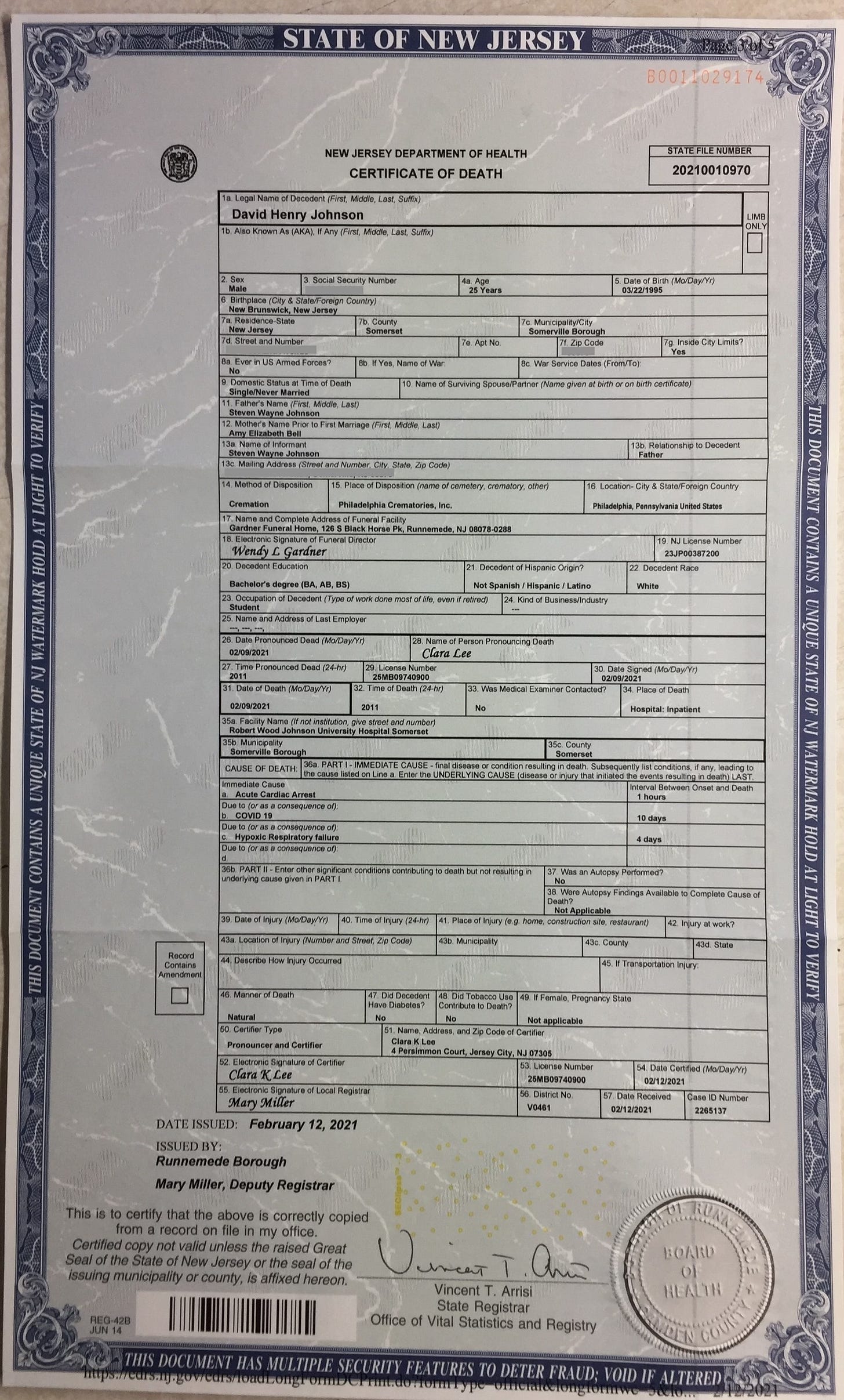

By Spring of 2020, when the pandemic began, David had graduated from Rutgers with his B.A. in History. He lived at home while in college, commuting to Rutgers New Brunswick after earning his A.A. at community college. He was a focused student, and received the Dean’s Award from Rutgers for maintaining a 4.0 GPA. He worked at a local country club while in school, as a line chef in the kitchen. In the summers he also worked at the local Jewish Community Center—managing the snack bar, assisting the CEO, doing stats for the basketball leagues, preparing the weekly senior luncheon, whatever needed to be done.

David decided he wanted to go back to school for his Masters, and was accepted at both Drew University, and Rutgers. He chose Rutgers. In the meantime, he had taken a job at the local community college in the tutoring department. His first day was scheduled to be the very day New Jersey closed down the schools and universities. Covid-19 had arrived, and with it, any chance David had of doing paid work had disappeared. Unemployment checks became his ‘pay’.

Our days throughout the rest of 2020 were not unlike most people’s. We tried to understand all the chaotic rules, tried to stay healthy even though no one seemed to know exactly how to do that, and vacillated between caution and bravado. The girls, my daughters, were all back to working in-office by year’s end after a brief span of working remotely from home. My husband, an engineer, was deemed “essential” from the get-go as his job was designing hospitals, so he went into the office every day in 2020, and beyond. David decided to postpone grad school until in-person classes resumed. When that would happen, no one knew. Life was turned upside down and nothing seemed to make much sense. He was drifting, but there was no place to land during this time. We all just wanted to get to the end of what was happening to us.

By Christmas, the whole country was obsessed with whether or not to “gather.” We had all managed to stay Covid-19-free all year, so decided to have Christmas as usual. Daughter #4 and her husband came to our home to join us.

In mid-January of 2021, daughter #2 came down with Covid. A co-worker and his spouse had gotten ill, and the spouse had died. Daughter #2 was very ill and I remember wondering which variant of the virus we were on at that point. She was suffering badly, with severe vomiting and diarrhea along with other symptoms, and ended up in the ER for seven hours while the clinicians there got her hydrated, and her GI issues under control.

By the end of January, all of us, except for the teenager, had had Covid. Daughters #1 and #3 had very mild cases. In fact, the only reason we knew that #1 had even had Covid was because we had antibody testing later in March and her quantitative result was at the upper limit—she’d had a robust response to the spike protein without really knowing she’d been ill. My husband and I had miserable cases, but not nearly as awful as #2 had suffered earlier. David was very ill at this time, with the same horrific GI symptoms as his sister had had. His sister, #2, was recovered by now, but not yet back at the office, since her company hadn’t cleared her to return to in-person quite yet.

David, so sick, was barely coming out of his room, and we were grateful that his sisters were around to help out, since my husband and I weren’t much good in our state of Covidness. David had a telehealth visit with our GP. The standard of care hadn’t changed: stay home, and if you get into trouble, go to the ER. So he stayed home.

On the 5th of February I was sitting on the couch in my Covid daze when I realized I hadn’t seen David for a day. I asked #2 to go up to his room and check on him—and to take his temperature, and get his O2 saturation—sat for short. O2 saturation is a measure of oxygen in the blood—your blood can hold a certain amount of oxygen, and your O2 saturation is the percentage of that capacity that it is currently holding. It should be close to 100. Healthy people are normally above 95.

Daughter #2 came back with a worried look, and told me David’s sat was 68. I was stunned and told her to go back and redo it. She did. It was the same. I told her she needed to take him to the hospital, a mile and a half from our home. She got him up, and helped him get proper clothing on—it was early February in New Jersey. It took him a bit of time because he was weak, and groggy, and not in any hurry to do anything but breathe. I knew that, because my husband and I were ill, we weren’t the right ones to take David over, and #2, having recovered and, as I firmly believed then, being immune, was the best choice for this.

David was admitted straight away. When they arrived and he was triaged, his oxygen was still in the 60s. The nurse called for oxygen immediately and said “I need a physician here.” Daughter #2 was only allowed to stay with him for five minutes. For inpatient admissions, no visitors would be allowed.

Over the course of the next five days, we got updates by phone, and here and there David would text a bit. The oddness of Covid hypoxia is this: people with horrendously low oxygen levels were still walking and talking. On the 8th of February, he seemed to have turned a corner. Things looked to be improving, including his labs and vitals, which had been so worrisome prior. He was even feeling better. He texted asking for seltzer water and a fan; #3 dropped them off at the front desk to be delivered to his room. The No Visitors rule was firmly enforced.

That time, when David was an inpatient, felt like an emptiness. We were cut off from him and him from us, as if we were in separate caves, and couldn’t be reached, or touched, or seen. But it seemed like he was doing better. This separation would be temporary.

The next day, on the morning of the 9th, #2 came into our room and woke me, saying David’s doctor had called and wanted to talk with me, and to expect her call. She said they were discussing venting him, that things had gone south.

When the doctor called, she said that David wouldn’t agree to being vented without his family—specifically me, his mother—being involved in the decision. I was floundering.

She said to me “He’s very ill. He has a dedicated respiratory team working with him and they’ll be with him all day, but if there’s no improvement by 4 pm or so, we need to make a decision.”

I was at a loss. I was extremely concerned about ventilation. I was also confused over the bad turn he had taken. The doctor kept telling me David was very ill. In hindsight, I now realize she was trying to tell me that he would probably die if he wasn’t put on a vent. I told her that it was ultimately David’s decision but I wouldn’t discourage nor encourage him either way. I knew now that he was scared, and he was asking me to help him to decide what to do.

The nursing staff called and said they were arranging a zoom call – he was going to be intubated around 5pm and we could all ‘meet’ by video beforehand. I got everyone together and at 5pm they connected with us: my husband, our daughters, our grandchild, and me. David was lying on a bed while clinicians worked around him. He was very short of breath, so didn’t say much. But we encouraged him as best we could, told him we loved him, and he said “I love you” too. I told him to take the rest offered, and when he woke up later, he would feel better for the sleep gained.

At 7 pm my cell rang. It was the attending doctor saying that David had coded, and that they had been able to resuscitate him, but he was critical. From this moment on, I felt as if I was drowning in an eddy. I asked her to keep me apprised of everything and asked what his prognosis was.

“I don’t know if he’ll live through the night,” she told me.

Not long after 8 pm my cell rang again.

“So,” the doctor began…I now feel as if I have PTSD when someone begins a sentence with ‘so’.

“So,” the doctor said, “David’s heart stopped again and we weren’t able to get him back this time.”

Everything went dark. Everything. I don’t remember much from the rest of that night. The doctor told me what to do to get my son’s body picked up, but it was two days before I even thought of that again. I just remember ending the call and collapsing into a primal grief that felt like ruination.

I felt ruined; a mother whose child has been plucked away. I said, “I can’t do this.”

My Covid story is this: my son died at age 25, after losing a year of not being able to work, to socialize, to attend classes, to be ‘normal’. He died because some psychopaths and sociopaths—as Richard Ebright at Rutgers labelled Fauci and his clan of monster makers—chose to play dangerous games with deadly pathogens, and then lied about it all.

David lost that year, and then he lost his life. Five years on, I still hope for justice. I don’t expect to see it in my lifetime, but I do hope it happens for David’s sisters to see.

It still feels impossible that this happened. Five years on.

Postscript: One year later, I had an interaction on twitter that has now somewhat vanished, but the other woman’s words have stayed with me. She said:

“People who live in fear of the virus are wrong and people who mock it are wrong.”

Yes.

The people who were THE most wrong were the ones advising to stay home unless you got "really sick." It was known very early that steroids and anti viral were being used effectively to treat covid. Ventilation turned out to be a very bad idea... I'm am so sorry for this family and all the others who are victims of the policies of restraining doctors "doctoring" and insisting only on "protocol" written by public health officials, bureaucrats. I'm also,still, very mad for them.

This is truly a nightmare, and as a parent my heart truly goes out to the author. I wonder how many different types of Covid there were. I worked in DoD, was mission essential, was among the very first to receive the jab. Ended up getting Covid four times, along with all of my workmates. None of us had the type of GI awfulness like the children of the author (thankfully) and only one of us ended up getting seriously ill. But, we ALL got sick multiple times. One of my SEAL friends developed myocarditis and has had two heart attacks since. What a mess, and with so many "unknowns" to this day.