Ten years ago, my father died. I still miss him so very much. I wanted him to see my sons become men; I wanted him to help my sons become men. I wanted my mother and him to continue to travel the world. I have wanted his counsel on so many things. What would he have thought of the trajectory of AI, of crypto currency, of Donald Trump? What insights could he have brought to bear on the meltdown at Evergreen, and in institutions of higher ed throughout the land? What would he have thought of absolutely everything these past three years?

I have many stories to tell about my father, but here, this week, I am only going to reprint what I wrote in the days after his death. As part of the immediate mourning process, I put together a website in his honor (inviting stories from others, plus photos and old documents, including a broadsheet announcing the sale of the family farm , a scholarship letter, a commencement address from Eisenhower, and party invites). On that site, I wrote the following tribute to him.

In Memoriam

Douglas William Heying: May 30, 1938 – April 10, 2013

My father.

My father taught me how to throw, how to bat, how to shoot pool (but not hoops), how to drive fast. He told me explicitly that I was not going to be one of those girls who threw like a girl. He taught me, through modeling the behavior over and over again, how to look both physical and intellectual risk in the eye and say: bring it on.

He craved nature. Many times he took my brother and me on camping trips to the southern end of the eastern Sierra, lovely spots on rivers in forests. Rivers that could be dammed with the consistent effort of one or two children over a couple of days. Sitting around a campfire one morning, my brother dropped a piece of apple in the dirt, and hesitated, not sure what to do next. My father picked it up and ate it, without so much as wiping off the pebbles stuck to it. We don’t waste food, was part of the message, but also: we are not afraid of a little dirt. In that same scene, in my memory, he ate an orange, whole. Peel and all. To demonstrate that you can. My brother and I were not convinced: yes, you can, but does that make it a good idea?

Many Springs we would drive, out far East of L.A., to see the wildflowers. His abbreviated color sense must have rendered that a different landscape from the one rich with oranges and yellows others saw, but he loved it. One Spring we also took a hot-air-balloon ride—my father and brother and me—over those same expanses. The wind came up, though, the landing constituted a minor crash, and he landed on me when the basket tipped. I remember a glider ride a few years later, maybe 1980, just him and me and the pilot. We’d been towed up to some thousands of feet by a plane, the line was released, and we glided down and rode thermals up over that same Southern California landscape. He taught me math and physics not only on paper and in conversation and game but also by moving us around three-dimensional landscapes together.

My father wanted to and to a large extent did see the world. He loved maps, and thinking about relationships in space. With all four of us, my father, mother, brother and me, I remember a helicopter ride in Kauai, landing in an impossibly small, narrow, dripping green valley, and taking off again over the Na’Pali coast. And another helicopter ride in Alaska, low over the glaciers, crevasses blue and terrible, to a lake where they pulled trout out as we watched, split and gutted them, fried them over an open fire. Best fish I ever had.

My father was strong, brilliant. He kept his thoughts to himself. Until he didn’t. Saw no need to interject always. Others would take care of the routine points and objections. He would contribute something brief but critical, once the rest was taken care of. Something no one else saw.

He did not suffer fools, period. Either successfully ignored them or somehow—circumstances depending—got rid of them.

He had, in the words of his son-in-law, an extremely under-developed sense of self-preservation. Which worked out—this odd failure to do the stats in an otherwise explicitly and consistently mathematical mind—because he appeared to be immortal. My children, his grandsons, adored him and assumed, too, that he was immortal. He did nothing to allay this suspicion by being dead for twenty minutes in April of 2012 before being brought back to life.

His long history of near-misses and catastrophes-that-were-not-quite-tragedies is legend. And with legend comes exaggeration and reconstruction, plus long after the fact interpretation of motives. How did the tractor end up in the ditch, back on the family farm? And going in to the Pacific Ocean fully clothed—mere amusing and drunken antics, pushing my mother’s buttons, or something else yet? And as for the white stallion in Tahoe in 1972, well. In retrospect, I love that he put me on that horse first. Of course, that’s the same refusal to engage statistics that he was so good at. How remarkable and exhilarating to pull off some impossible feat, unscathed. Scratches and bruises and the occasional broken bones are to be expected, after all. An unscathed life is not worth living—that’s what Socrates said, right?

Road trips, my father always at the wheel, my mother riding shotgun, of course, map in her lap. Every Summer. He drove and drove and drove. In Yellowstone, at the beautiful but odorous sulfur pools, the keys get locked in the car. A BMW, but I do not remember which one. And the passive voice there is a feint—he locked the keys in the car. An honest mistake. So he went in through the trunk, took out a back seat, and retrieved the keys that way. Years earlier, on the stretch of 395 between Mammoth and Lee Vining, at night in a snow storm, the car runs out of gas. He let the car run out of gas. My mother was furious, and he hoofed it into the blinding-white-darkness and somehow came back soon, with gas. Summer road trips from then on, for the most part.

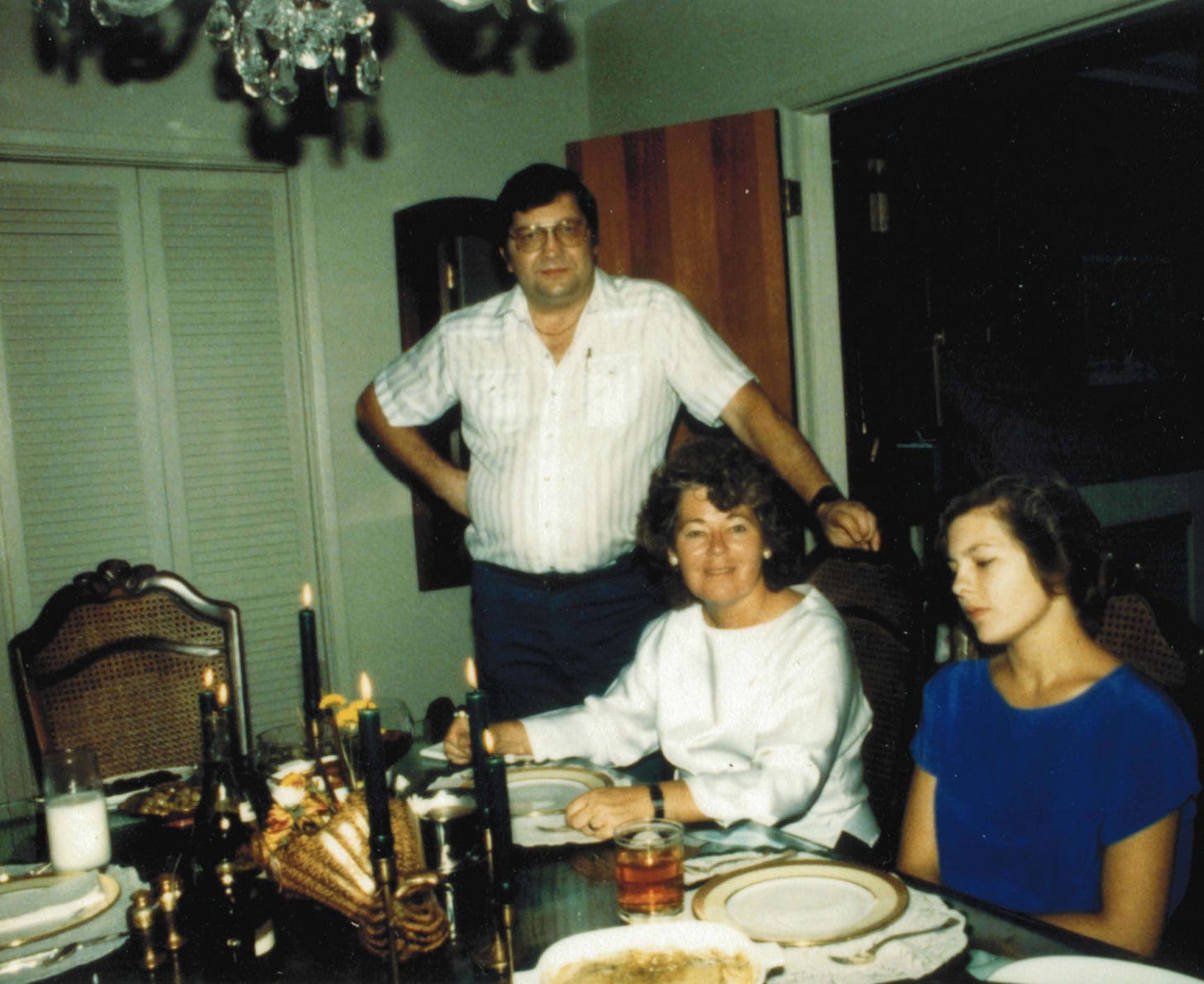

My father was stubborn, and quietly charismatic. He had a soft spot for many things that he did not admit—among them cats, and being watched out for by those who loved him. His photographs—the many that he took, some of which he developed himself in the dark room behind our house—reveal some of his preferences: for his wife and children, and later his grandchildren; for natural and architectural beauty, for pattern anywhere. Macros of snow clinging to cedar branches, cloud formations, water reflecting, deer fighting.

Urged by his own father to get a college education, he went to Notre Dame and fell for engineering. Played the field, academically—civil engineering, which was apparently too mundane to keep his interest—followed by aeronautics, then electrical engineering, and then a new major, one with a non-descript name—“engineering science,” all the physics and math he could get, but still in the applied context of engineering. Fell into the computer business almost before there was such a thing. June of 1960 he graduates, takes a job with Westinghouse in Pittsburgh—having also been offered a job by Sandia, in Albuquerque—and does a sort of technical rotation. Later, he doesn’t even remember what was behind door number one. Door number two was computers, and he was hooked.

He told me that much of what he did, in his work, was at the interface between software and hardware and—more to the point—in the interface between the programmers and the hardware developers. He, who understood the science on both ends, helped the humans communicate with one another, so that the product didn’t blow up on either end for lack of understanding between the organisms. Bits and bytes, yes, but genes and memes, more so. Solving analytical problems—and figuring out how to get the people involved to understand each other. Quietly insistent on rigorous, careful, honest work and human understanding.

He took me into his work, sometimes, in the ‘70s, and I remember the room that held the mainframe, vast and important and vaguely loud but not in an insistent way. No human beings. This was not a room for people to work in, to live in, but it was certainly a room for people to visit, to see proof of what we can do. He wanted me to see it.

I remember going to games with him, too: Dodgers and Lakers and Rams and Raiders, plus the occasional Harlem Globetrotters game, and a couple of Notre Dame – USC games, too. I remember enjoying the athletics, and the time with him, but not understanding, except for college ball, why I was supposed to feel investment in one or the other team. For the most part, these guys weren’t even from LA. I got the college rivalry, though, enough to rib him later, when I went to the University of Michigan for grad school, and the Wolverines beat the Irish, although secretly I was rooting for ND. When one year an ultimate frisbee team I was on played at Regionals, which happened to be in South Bend, I got to play competitive sports near Notre Dame, and boy did I care who won then.

There was a different kind of game we played, he and I, that involved set theory—I can see the orange ‘70s plastic of the box, and the dice with union (È) and intersection (Ç) symbols on them instead of numbers, but I remember little else about it. He had briefly taught calculus while a grad student at Carnegie Tech, and I remember how dismayed, even disgusted, he was by the elementary school homework I brought home which was called math. He quickly dismissed anything smacking of mnemonics absent first principles—he taught me that memorization without understanding was pointless, and in fact, counter-productive. And he replaced it with better stuff. One such fix, for some time—a week, a month, maybe a year—involved me doing the work in decimal, and also in binary. I loved it. In 7th grade, I turned in a math test before anyone else had finished, and the teacher responded by accusing me publicly of cheating. To this day I do not know the details, but my parents were sufficiently outraged that that man, that teacher, was soon gone from the school. Later that year my father encouraged me in my math fair project on the geometry of billiards, and soon thereafter started taking me to math competitions at UCLA. He never talked about why math was necessary, or valuable—he just modeled that truth, and kept alive in me the enthusiasm that was already there.

My father was emphatic that I should not and would never be helpless. When it was time to build a fence in our backyard, and I had my nose, again, in a book, he insisted that I be actively involved in the project. He was angry with me rarely, but my resistance to helping build that fence prompted one of those times. When I became a teenager, he gave me hand tools. When I got my first car—a then 10-year-old ’76 Toyota Corolla—he would not let me drive it until I had changed both a tire and the oil, myself. When I started heading to tropical rainforests to study animals, he wanted to know the specs—how many rolls of what ASA film was I taking; what kind and size of battery did I need for the solar electricity system I was putting together to power a laptop for data entry; what was the draw on those greedy pre-LED headlamps. I always knew if I had screwed up, because he would stop asking questions.

In the mid-80s, as at many other moments, my Dad was full of life and intellect, but without much outlet for his sense of physical adventure due to ankles crushed and becoming ever worse from the massive accident in 1969, five days before my birth, which easily could have killed him. Sometimes full not only of life but also too full of alcohol, he thus totaled a car, and relatively soon thereafter another—nobody else was hurt in the process, and he himself walked away from both accidents, too. A few years later, I came home late one night, flying a little, and thought I could pass, tried talking with him. He was in the computer room, as always, some low-baud modem locking up the phone line, occasionally dropping the connection and then emitting its iconic song again. He knew something was up, though, and somehow, without words, made it clear that this was not okay, and that he would come get me anytime I needed a ride. A rare case of “do as I say, not as I do,” from him, although in the end, he was finally following his own advice on this point.

My father had big appetites, not just for speed and life and risk and drink but also for actual food. Not for mere calories, either, but for flavor and sustenance grown together in an organism and prepared he cared not how—simply or elaborately—so long as it was done well. Whenever I visited my parents in Berkeley, he and I would go to the Cheese Board—a cheese cooperative, every city should have one—and swoon. We came back, always, with soft mold-ripened cheeses, and some bleu, St. Agur if they had it, and a hard sheep cheese, and spread or sliced them on fresh sourdough. My mother was and is the gourmet chef, making fabulous dishes, often meat, often French. He ate heartily, of her food, of that in fine restaurants, of good food wherever he found it. Wherever he was, whenever it was, if the soil or sea produced it, he wanted to try it—terroir at its most fundamental. He loved food fresh and real: berries and rhubarb, oysters and mussels, leeks and potatoes, pork and lamb. His go-to recipe when we were growing up, on those rare occasions when my mother did not cook, was fettuccini alfredo, a classic that began, “soften one quarter pound of butter…”. Some cheese and cream later, he and I would make excuses to lick the bowl clean. In the Fall of 2011 his sister Shirley and I shopped the Farmer’s Market for his favorites, and cooked them, and we all ate together, and it was good. The last thing I made that he ate was Thai chicken soup, just a few weeks ago, and now that reminds me of him, too.

A few more memories…while building a shed in the Berkeley backyard in 2003, he was ripping a sheet of plywood, the blade of the table saw grabbed, and the ends of three of his fingers were now across the room. My mother was napping upstairs. Not wanting to bother her, he collected his fingers in a baggie, filled it with ice, wrapped a rag around his bloody hand, and drove himself to the hospital. A month or so later, grafted and healing nicely, it seemed to him like time to install a floor. He argued that you don’t cut boards with a table saw, and what could possibly go wrong when using a chop saw? My brother came over from Marin, and I came down from Olympia, and we did it with him, but kept him away from the saw. It just seemed too soon.

One year in the mid-70s, a giant blaze in the hills above our home in the Palisades threatened, more than any other before or subsequent. Fire was visible and huge not three blocks away, flames licking at houses that were disappearing, and all the dads in the neighborhood who hadn’t evacuated their families stood on their roofs with hoses, wetting down the tinder that was their homes. Over my mother’s objections, my father took me up with him, let me help, let me see—the only child on any roof around—and it worked out. I fell asleep that night on a pile of blankets on the floor of my brother’s room, where we and the pets were ready to be scooped up and evacuated by car should it come to that. We woke up the next morning, sinuses filled with smoke, fire out, that strange orange desert-after-a-fire light streaming in all the windows of the house, my parents sitting at the kitchen table drinking coffee, looking like they couldn’t quite believe the worst was over.

In the days after his death, I drive his car, a BMW 5-series. Appropriately enough, I almost get a ticket doing so. I’m “only” going 33% over the speed limit, as I explain to my children later (80 in a 60), which affords me the opportunity to provide a brief math lesson, much like the kinds of lessons my father often gave me. Their eagerness and joy at finding math everywhere reassures me that he lives on in me, and also in them, and that I internalized some of his ways sufficiently to spread his ways of thinking about the world.

Oh Heather, I wish I could give you a hug. Reading this it's so easy to understand why you miss your father so much.

Thank you, Heather. Like you and your family, I grew up in Los Angeles and spent many memorable days camping in the Sierras with my family, going to the Mojave desert to see the wildflowers, and even watching my heroic father on top of our roof during the Bel Air fires (no, he didn't bring his 4 year old up with him, but wished he had as I was scared to death). All of those memories come flooding back as I read your beautiful tribute to your father and the values he instilled in you. Lucky are your sons who do still get that part of your dad. And those ripples will probably continue for generations. Sadly, we never really think about the effects our ancestors have imparted upon us, as silent and powerful as they may be. And thank you for the work you and Brett do. Mere words will never be able to convey the appreciation we have for you both.