Today’s heartbreaking essay is by Tara C, the mother of Mila Neufeld. As you will soon learn, Mila (pronounced Mee-la) was an extraordinary young woman. Mila was strong and smart, gentle and compassionate, kind and protective and wise, especially for one so young. Despite all of that, Mila did not make it through.

As the Truckers Convoy made its way to Ottawa in the end of January, Mila’s parents went out to greet them, as did so many others, untold thousands across the vast highways of Canada. Tara passed out flyers to the truckers, single pages that provided hints about Mila’s short life, and which concluded thusly:

I sent letters to the Prime Minister, the Ontario Premier, to the federal and provincial Health Ministers, to the Ministers of Education. Nobody even wrote us back. Nobody cares.

This is not just about our child, it is about Canada's children. Thank you for what you are doing. It matters.

Our children need their world back. We have stolen some things that we can never return.

Mila was a singular, amazing young woman. She was deeply loved, and will be forever missed by the many who knew her. The truckers and their supporters and friends are doing this for all of us. We thank them. We thank you.

For Mila, and for all of us, please

Hold the Line.

Mila’s Story, by Tara C

In her grade 12 year, our daughter, Mila was given an assignment to write her biography. Who was she? Who did she want to be? Her essay was unlike any one would expect. Instead of writing about her accomplishments, of which there were many, she told the story of a little deer. It was a doe, in fact, that her father and her came upon while driving back to our farm from the city, late one evening. It’s not unusual to see dead deer here, but what made this deer different from most is that she was still alive, her back legs severed at the knee. She tried to get up, repeatedly, using her exposed bone where a delicate hoof should be to propel her, but she just collapsed over and over.

Why would our daughter tell this story as her biography? Because while other cars drove past, swerving around the suffering animal, she and my husband, pulled over, brought the animal to the side of the road, and soothed it before swiftly slitting its neck. “Swiftly”, that word is important. Her teacher, moved to tears by the story, suggested the word “gently” to smooth out the edges. No, Mila wouldn’t have it. Kindness isn’t always gentle, she explained. Swiftly and assuredly, that was right. She wrote this story as her biography because, as she wrote, “that is the person I want to be”. The person who did the hard thing because it was right. And that is the person she truly was. Morally driven. Deeply connected to the natural world. A young woman who had a profound sense of meeting what was hard and painful, over the ease offered up by our culture.

Mila grew up on our farm in a rather idyllic life. She raised goats and meat rabbits and helped in the garden. When she wanted cream for the bucket of blackberries she picked, she wandered into the field, got her favourite cow, Ursula, and milked her. “Spare a little cream, Ursula?” And of course, Ursula, who had seemingly great affection for Mila, just as every animal on our farm did, was happy to oblige.

Mila played on the boy’s hockey team since she was three years old. She started being the little tyke on the ice, turning to help her opponents up every time they fell, to growing into the nickname “Bulldozer” as she took on every 6 foot 2 inch powerhouse that dared to slam into her. She was a fan favourite in the stands, the parents yelling, “Yeah that’s right, make her mad! See what happens!” We called her our ballerina warrior on the ice.

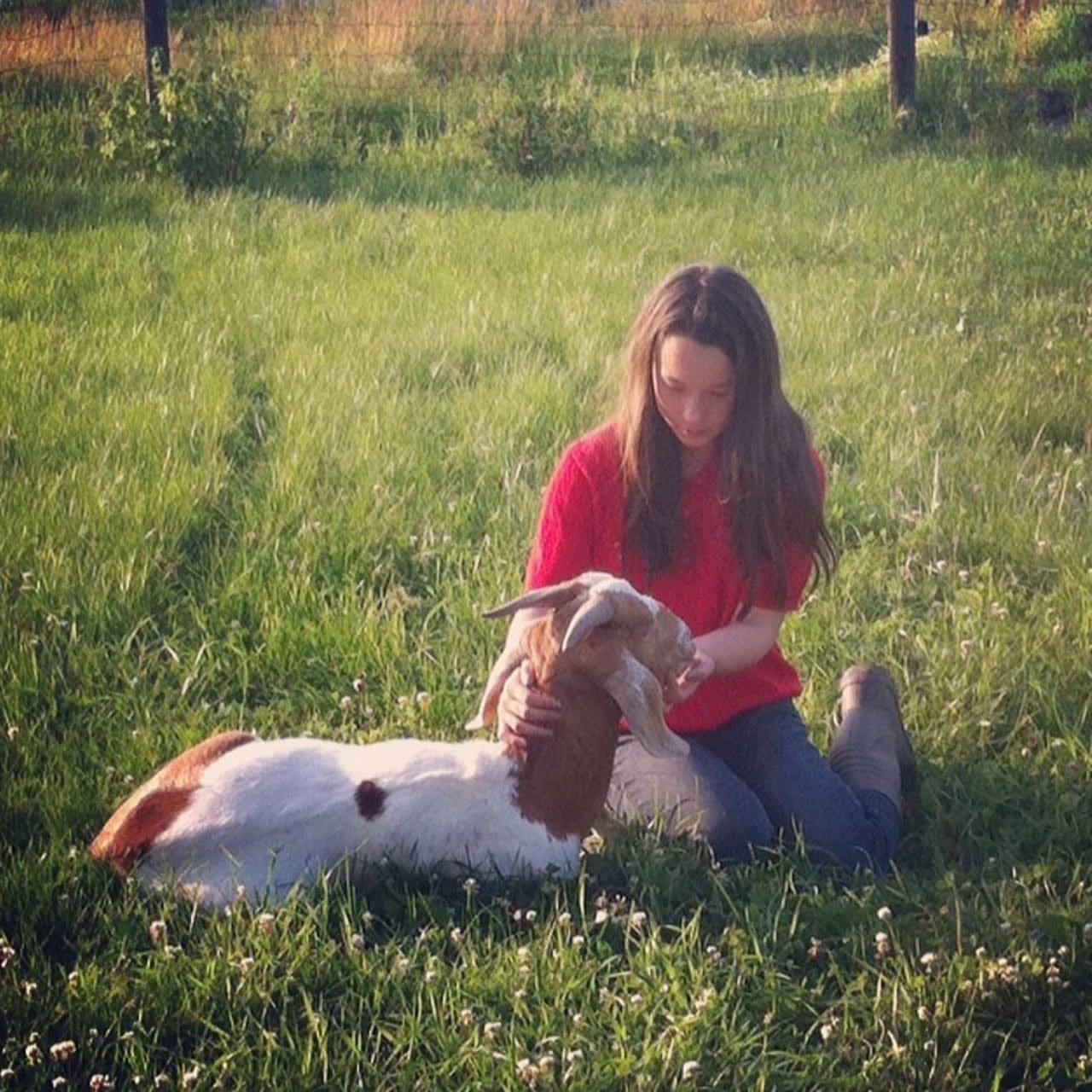

We harvest our own animals here. With livestock, as they say, comes dead stock. There were so many lessons Mila learned in her condensed years. When her beloved goat broke her back, she asked her papa to carry it onto her lap and there she sat, on the grass, under the sun, petting her goat and talking to her privately for over an hour. What she said, I do not know. I watched from the kitchen window. All I could see was a little girl, still round and soft in her nine years of age, weeping and the calm goat, accepting her touch. When she was done, she called her dad over and said, “Okay, she can go. She knows I love her.”

My inclination is to spend all of my time sharing stories of our beloved Mila with you. I’d like to tell you about her homeschooling years, when we would wake up at 0600hrs in the morning to notes from her telling us she was in the forest with her bow, looking for adventures. Or about the novels she wrote about wolves and barn cats when she was only nine years old. I would love to share a coffee or two and tell you about the 98% average she maintained throughout high school and the peer tutoring she offered to those who struggled. Maybe I could play you a recording of her jazzy saxophone number or show you the video of her playing her ukulele in a hammock, with two barn cats snoozing on her lap. Her barn cats would sit outside our door, waiting for her to leave the house so they could follow her wherever she went, moving in great calico tumbleweeds behind her.

As much as I want to stay there, in those memories of my beloved, I need to crawl out and do this part now. The part where I tell you the story of Mila’s death and the events that precipitated it. The part where, in the rubble of my life, I muster what I can to share with you our pain in hopes that there is something here that might make a crumb of difference.

Mila, illuminated and mysterious, was a creature beyond this time. She wanted to be a midwife and she would have been a glorious one. When COVID hit, our part of the world, Ontario, Canada, imposed some of the most draconian and aggressive measures of anywhere in the world. A couple of weeks to flatten the curve, right? Initially, like almost everywhere and everyone, we obliged.

Schools were closed. It was near the end of Mila’s grade 11 year then. There were no classes online at that time. A mad scramble ensued to get these kids some sort of education. Eventually, schools tentatively opened for some. We had the option of keeping her home or sending her in. She insisted on going. For the next few months, and into the fall of her graduating year, schools opened. Then schools closed. Then schools opened. Her friend group shrunk considerably. Most parents abided by the “no socialising” rule. There was really nowhere for them to go anyway. Theatres, live music, restaurants, and even places like bowling and the roller rink were closed. Instead, the dwindling friend group that Mila was a part of had random, clandestine meet-ups—in a friend’s frigid barn, or someone’s basement.

At that time, Mila wrote in her diary, “everyone is always crossed (high) and it’s pissing me off”. It was October of 2020. Their school board opted for “mono classes” to keep everyone safe. This meant that cohorts of kids went to school and entered one and only one classroom, six foot spacing between them, their masks on all day long. They sat there until the end of the day. They ate their lunches there too (masks off and on quickly, if you please). They were not allowed to use their lockers or gather for any sort of social interaction. Their book bags had to stay with them. When we learned that the school bus driver was mandated to keep all of the windows open on her hour long bus drive into school every day, despite the temperatures hovering around -20c, we handed her the keys to the old farm truck. She started driving herself.

Worried about the effects that this type of bizarre environment would have on her psyche, we begged Mila to just do online courses, but she refused. She would take what she could get of seeing and being around other people. With hockey and rugby, school band, peer tutoring, and entertainment venues closed, the few meagre moments she had seeing her friends—or their eyes, at least—was better than nothing. It was at this time that she started coming home from her part time job pumping gas at our little country, full serve gas station (yes, they still exist!) and writing about the interactions she had with customers. She wrote stories about the Jehovah’s Witness that people were openly making fun of. She felt bad for him so she asked him for one of his pamphlets. She liked how it seemed to make him happy. She wrote another story about complimenting a middle aged woman on her beautiful hair. The woman broke down into tears and asked Mila if she was teasing her. “No!” Mila assured her, “Your hair is truly beautiful!” The woman replied, “I have cancer, this is a wig. I thought everyone could tell. Thank you, thank you for your kindness.”

In November, just over a month after writing in her journal that she was frustrated with her often “crossed” friends who, like many teenagers in our rural areas had started using blackmarket, high THC vaping pens as their drug of choice, Mila wrote in her diary, “I tried the pen, I like it”. Within two months, Mila wrote that she was using these pens every day and that she was in trouble. Her unique biochemistry, always exquisitely sensitive, had met its match. The great Russian roulette in life.

Mila went to the school drug counsellor a few weeks later, once he came around again. The school board here contracts out a private company to employ roving counsellors who make their way though dozens of schools, sometimes appearing for a few hours every week or two at any given school. The counsellor, not knowing Mila and not talking to any of her teachers, teachers who would certainly have been shocked at the swiftness of her self-identified problem, did what he was trained to do for everyone walking in his door - he told Mila to moderate her usage, “maybe just smoking in the evenings or once her homework was done” and that it was “probably a good way to cope during COVID”. Mila told her friends that he had given her permission to carry on.

Schools closed again. Classes moved online. Mila couldn’t get the classes she wanted because she was vying for limited space against a whole province of kids. Word came back from the universities ‘Yes, you’ve been accepted, but you must be vaccinated’. She was worried, but she was also Mila - pragmatic and a gifted, critical thinker. “I’m not convinced, convince me” is how she rolled. She would wait for the convincing, but until then she would not accept the vaccine.

She spent weeks agonising over ways to get around the mandates to be vaccinated to attend the university program she wanted. She wrote emails. She spoke to admissions. She brainstormed. When it became evident that it wasn’t going to happen, she considered using some of her savings to travel around the world for a year, volunteering on farms as her older sisters had when they had graduated. No, it turned out, that was not going to happen either. Canadians were not allowed to leave their country unless they were vaccinated. “I’m in prison” she said.

Her use of the marijuana pens increased. As the new year of 2021 came, so too did the pressure to decide what to do next. She was itching to test her mettle, to head into the world and take on what it had to offer, but all roads pointed to… nowhere. The road had one big stop sign on it. Out of desperation she applied to a university that some of her friends would be attending that had a business/accounting program that didn’t require vaccination. She was unenthused about her future, but didn’t know what else to do.

In February, word came that while she was accepted into the school, the plan to stay in residency for the first year, as all of her friends were doing, wasn’t going to happen. She needed to be vaccinated for that. She started looking at apartments near the school. Who would she share an apartment with? She didn’t know anyone, but would find someone. She started looking through advertisements and saw that the need for vaccines pervaded even there.

In March, the seams of her life were unravelling. She wrote:

“I just miss being able to see faces, to be able to stand next to someone and not have to worry about being yelled at or told off, or being able to just walk down the streets of downtown Kingston with my friends, and just see everyone doing normal things. I miss being able to just ‘go out’ and do whatever you want, without having to worry about restrictions or masks or gathering sizes or anything like that. Everyone is saying how we’ll never have the ‘old normal’ again – that we’ll have a ‘new normal’. But to be frank, I don’t want any part of what is going on in our world to be normal, because this isn’t normal. Humans are social animals and we need that social aspect in our lives to be happy. I hope that our world will be back to the ‘old normal’ as soon as possible, because no matter how long things are like this; whether it be two years or eight, I will never view this as normal. I’m also very upset that this had to happen in my senior year. All of my friends and everyone I know will soon be moving away; and I didn’t even get to have that last year with them, or a prom or a graduation. It’s really disappointing and I’m very upset at how distant everyone is with each other now.”

She was a girl who was raised on the land. A girl who knew and found her touchstone of truth in the authentic and the wild. And there were our leaders, our authorities, saying “No more, this is what you have now - masks, isolation, distance, the war with our own bodies and our selves.” All of it unrecognisable.

She was using the marijuana pens daily. She was no longer sleeping, often taking “a rip” off the pens throughout the night. Her school was dealing with an explosion in kids using these pens at school. The principal, in desperation, ordered the doors be taken off the school washrooms. Our children, living like zoo humans in the synthetic construct of a life.

We could see she was struggling. We talked to her, sat on her bed with her. We offered to arrange counselling if she would rather speak to someone else. We could see her sadness, her disconnection, a smile that faded too fast from her face. She assured us she was okay. “Just stressed about all this stuff, trying to figure out what to do” she would say. Or that she was PMSing. Or that she was just overwhelmed with school and COVID and not knowing what to do after graduation. We did what we could to reach her. We played board games every night after our family dinners as we always had. We talked to her about options. We spoke as a family about how twisted the narrative is, but there was hope in it still. We had covert gatherings and interactions with family and friends. We tried to inject healthy socialisation.

We had no idea that she was using those pens to escape. We had no idea that she was in the throes of “marijuana induced psychosis”. She told her friends about terrifying hallucinations she started to have. After her death, her friends told us “we thought she could see ghosts”. They had never heard that somewhere around 15% of adolescents using marijuana, especially the high THC marijuana found in these pens, would experience some sort of psychosis or serious mental health issue. Ghosts, that’s what they thought the problem was.

In April, now floundering, Mila started making bizarre decisions, completely foreign to her make-up. She would not go to university at all. She would go work. No, she would go out west and plant trees. No, she would go out east and work and kayak the Atlantic. We were dazed and confused. What was happening? We sat with her for hours and tried to untangle her thinking. We all cried together. We offered help. We offered everything we thought of. She was desperate and we could see it but there was no reaching her reason. Of course now in retrospect, we see, she could not reach her reason either. She was trapped in a hijacked mind.

She went to see the drug counsellor again. She told him that sirens and ambulances were following her everywhere she went. She told him that there were voices, “like background voices, in a train station.” Again, he spoke to her about moderation. When we met with him and his supervisor, weeks after Mila’s death, my husband, an ER physician, asked what type of medical intake they do with these kids to identify medical emergencies. “None” they said. “We use the first four or five visits to build up a relationship.” “You have to understand,” they told us, “Mila was an anomaly. We don’t see honour roll kids come to us on their own. We see troubled kids being dragged in by teachers and parents. We don’t have ties to the school nurse and we are not here to identify medical needs. Our framework is one of relationship building and usage mitigation.”

Mila did not need a friend to tell her to mitigate. She needed immediate medical attention.

School was off again. She was taking one calculus class online. She went to work and did her job, charming the world with her thousand kilowatt smile while she crumbled inside. The world loved her.

And all around her, the lockdowns persisted while the authorities insisted: “The new normal. The new normal. The new normal.” The old world was gone, the new world had arrived. She could have navigated it, would have persevered as she always did, but her brain was no longer her domain. Her good reason and sound judgment were circumvented by a biochemical shit storm that she mistook as her own “fucked up mind”.

On the evening of May 10th, 2021, I had a dream that an angel stood before me. Her outstretched arms were empty and her water soaked wings dripped a puddle around her feet. Her head was bowed. “I failed.” That was her message.

We were awoken by the police knocking on our door. Our Mila, strong and true, had died of suicide.

Mila was far more than what is portrayed here. If you are interested in reading more from Tara about her daughter, and their lives, I highly recommend both of these newsletters:

Update, October 2022: Mila’s extraordinary mother has written about another factor that contributed mightily to Mila’s death. Read it here.

Everyone needs to read this story and mourn for Mila and all the lost children. "Our children need their world back". What our children will need to really heal is an extraordinary effort to "right the ship" that callously derailed their lives and psyches these past two years. Are we up to the task? I sure hope so. I'm sending this post to my Congressional Rep and Senators. This should be our priority as a nation. Sending love and healing to Mila's family. Thank you Heather.

I read your essays, Heather, because you bring some degree of reason and balance into my thinking. I have to; otherwise I would despair. I know I need to seek out wisdom in this upside-down world.

And, the comments here are compassionate and sympathetic, and I appreciate that. It's a balm. Maybe that will prevail if we ever get to a reckoning.

But, I'm am raging; this is but one of the beautiful lives we have sacrificed to safety-ism. I am furious, and I can not imagine these parents' agony. These are not tears of sorrow streaming from my eyes as I read this letter, they are tears of fury.

So many lies, so much evil. Their lust for power and their politics as religion have destroyed us. Science lies in its grave alongside its sister, theology, murdered by simple greed.