Five years ago today, on May 23, 2017, The Evergreen State College melted down in a fury of outrage, confusion and ignorance.

Here is a brief précis of what happened1:

A pedagogically innovative, public liberal arts college, in which students of myriad backgrounds were able to do rigorous, creative, analytical work, was undone by the collaboration of a new president with a cabal of faculty and staff who insisted on their vision of “social justice.” Videos of protests2 that engulfed the campus in May of 2017, taken by the protesters themselves, were but one tiny piece of the madness that took over a once remarkable institution.

In the months leading up to the protests, President Bridges pandered to the protestors; privately blamed lack of action on his provost (while his provost was equally certain that it was the president who needed to act); and tried to silence dissent within the college by offering goodies to those who were speaking out in exchange for their silence. Furthermore, he empowered “social justice” faculty by allowing them to push through policy changes, silence dissent from their colleagues, and make slanderous claims against other faculty, with no correction or follow-up. For months social justice faculty wrote nasty and often epithet filled emails directed at Bret Weinstein because he questioned the way the college was being run, after which several dozen faculty demanded an investigation of him for the mortal sin of accepting an invitation to appear on FOX News. They had become faculty trolls hiding under Bridges.

Once the protests broke out, the president hired a public relations firm to spread false narratives, and ordered the police to stand down while protestors hunted car-to-car for “particular individuals” on campus, barricaded buildings, and held people hostage. In a private meeting with upper administration and protesters (which was filmed and uploaded to the web by protesters), Bridges said of those not supporting the college’s equity agenda that “They’re going to say some things that we don’t like, and our job is to bring them on, or get ‘em out . . . bring ‘em in, train ‘em, and if they don’t get it, sanction them.”

In that same meeting between activists and administrators, the activists asserted that science faculty are the worst offenders. But what is the offense? The claim is that the offense is racism. The claim is absurd. Racism has, of course, been a scourge on humanity from time immemorial. But at the societal level, we were moving in the right direction. People were becoming more tolerant of, and less bigoted against, those who looked or sounded different from themselves, or who had different histories and cultures. Evergreen was perhaps the most progressive college in the country; tolerance and compassion were cherished ideals. Thirty years earlier, Bret had stood up against truly racist practices adjacent to his own undergraduate institution. In 2017, he was standing up against divisive and racist practices at Evergreen, and for this he was himself called a racist. No actually racist events were ever described or discovered at Evergreen3. But that didn’t stop the mob.

Factors contributing to the extravagant, fantastical, and wholly unnecessary events at Evergreen in the Spring of 2017 are many and diverse. Some factors appear to have been central—such as the long history of racist policies and actions at American institutions—but were actually strawmen, weaponized by those who prefer division over solution-making.

Other factors were in fact key, but are largely invisible to most observers: Science has come to be funded largely by federal grants; because colleges and universities get a substantial percentage cut of all such grants, institutions of higher ed are increasingly dependent on researchers who bring in large grants; this in turn privileges Big Science—long-term projects that require expensive equipment and massive teams, in which both accountability for most individuals is lower, and there is less emphasis put on individuals being able to actually do complete science, from beginning to end. The way that science is now funded has thus created a tremendous number of highly trained, highly credentialed, cogs, who know one piece of a puzzle, or one methodology, very well, but are not good at hypothetico-deduction, or indeed, much of the logic inherent to the scientific method. Such scientists are more likely to expect to be treated as authorities simply because they have credentials, because if you ask them to explain complex ideas simply, or to consider the evidence for the claims they are making, they often cannot. This, in turn, leaves a populace that is simultaneously smitten with the idea of science—look at all it has done for us!; intimidated by the complex jargon and technology that seems to be necessary to do it, so often inclined to just trust the authorities; and also justifiably suspicious of yet another privileged class who receive goodies (like reductions in administrative tasks at their professor jobs) that other professors can only dream of, while acting arrogant and entitled with those who don’t share their credentials.

Most people who have participated in protests, riots, or mobs on campuses or in the streets these last few years are unlikely to be aware of the changes described in the last paragraph. But some things are obvious to nearly everyone. We have increasing disparities in wealth and opportunity between those at the top and those at the bottom, with increasingly little space in the middle. Young people feel acutely the lack of opportunities they are facing. How can they pay for college, much less ever buy a house, and what meaningful work will be available to them in their lives, in this 21st century world?

Into that landscape, enter demagogues who offer simple sounding solutions. Demagogues like Robin DiAngelo (author of White Fragility) and Ibram X Kendi (author of How to be an Antiracist), who preach division and encourage suspicion and hatred between people who look different from one another. And solutions like the BlackLivesMatter (BLM) movement, and Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) offices and officers. These “solutions” use so many glorious words, you would have to be crazy or evil to disagree with anything they propose—or so they would have us believe. Inside these movements and organizations we find, however, the policing of speech and behavior, encouraging spying on one’s peers and reporting unacceptable behavior, and discouraging the open discussion of ideas and solutions that don’t sound like the currently fashionable thing. This “equity agenda,” to use the language of Evergreen’s president, is a fast-tracked orthodoxy about which you are not allowed to disagree.

The weaponizing of the anger and angst of young people for personal or political gain became all the more polarizing when one of the country’s two major political parties took up the mantle of BLM and DEI. Those who have no interest in addressing economic disparities can divide and conquer by focusing on immutable characteristics—race and sex—and insist that those are the primary characteristics that predict outcomes today. Furthermore, the election of Donald Trump, which did not mark the beginning of the divisive political rhetoric, but certainly marked an accelerating point, further polarized nearly everyone. For a while, it seemed that even the usually clearest headed among us were adamantly, vociferously, rabidly, even, either anti- or pro-. The hatred that accompanies such tribalism is delicious, and deadly.

At a more local level—at Evergreen as elsewhere—opportunistic activists who were LARPing as scholars and academics indoctrinated students rather than educating them, whipping them into a frenzy of misplaced anger. Young people everywhere and throughout time can be enticed to such frenzies: passion, self-righteousness and groupthink are intoxicating in the moment. It was but a handful of faculty and staff at Evergreen who created the frenzy, but their reach was far indeed.

And the success of the Evergreen LARPers was secured by a few more factors: a college president who worked hand-in-hand with the activists to foment dissent among the faculty, and the fact that the vast majority of the rest of the faculty and staff abdicated all responsibility for what was happening. The adults left the room, or revealed that they had never been adults at all.

There are several details of what happened—both in late May and early June of 2017, when Evergreen was at fever pitch and violence always seemed imminent, and also in the early Fall of the same year, when Bret and I were in mediation with the college—that we have not discussed publicly.

One is that one of the men who marched with Martin Luther King Jr. in the 1960s, a civil rights activist, community development leader, and a black man himself, whom I am not mentioning by name only because I did not have time to ask him if I might, contacted us to say: Please allow me to come march with you, and to bring with me some of my civil rights activist friends, on the Evergreen campus. He said: these people who have taken over your campus, they are destroying King’s dream.

We were considering his offer, when a new round of violence on campus made it too dangerous to proceed.

After classes ended for the year, we were in a holding pattern. The college ignored our legal requests to sit down and discuss what had happened for the entire Summer—we were ultimately told by one person inside the administration that president Bridges, apparently exhausted from his grueling experiences being a hapless fool who encouraged his own abduction, had taken vacation for the entire month of July. We were in purgatory—were we still tenured professors, or weren’t we? Our hometown had become unpleasant at best. The college did find time, that Summer, to hire some of the most egregious student actors, the ones who had helped incite the protests, into paying positions at the college. Up was down, black was white, and through the looking glass we went.

In the middle of that endlessly surreal Summer, a Public Records request that I had made many weeks earlier came through. Just as then-Police Chief Stacy Brown had suggested they would, the files I had requested revealed some of the actual violence that student activists were being allowed to enact on other students. But the most interesting thing about the request was that it arrived in our mailbox with a hand-written note from Evergreen’s Public Records Officer, whom neither Bret nor I had ever met. Her note was kind and human, striking a tone that had been lacking from nearly anyone at Evergreen since May 23 of that year. In it, she told us that she was thinking of us, and that she appreciated what we were doing, and hoped that we were staying strong. This stranger took the time—and the risk—to reach out to us and connect. It meant a tremendous amount to us. It should not matter, but the author of the note was also a black woman4.

We finally sat down to mediation with the college after our contracts for Fall of 2017 had already begun. We were due to begin teaching full-time programs within two weeks, in programs that were overfull, which was always true of our programs.

Mediation did not go well. We sat in two separate rooms—us in one room with our lawyers, and the representatives of the college in another with theirs—separated by a wall from people whom we had known for years, one of whom had been at our home just weeks before. Through the mediator, we were asked to apologize to the college. We gaped. We were still fighting for our lives at Evergreen at that point, a college whose mission we loved and whose experimental curricular structure is extraordinary, when it works. We offered to organize a conference at Evergreen, one with a truly diverse and inclusive roster of speakers—from that same 1960s civil rights activist, to modern day heroes and scholars of free speech and education. The college responded that they saw no need for such a conference, and they offered us panic buttons to have in class.

There was no hope for reconciliation. The college wasn’t interested in reconciliation. The college was, in fact, proud of its insanity. They continued to double down.

The mediation resulted in a monetary settlement and a promise to never seek employment at Evergreen again. The college also hoped that we would agree not to talk about any of this, but of course we would not. Totalitarianism rarely makes spectacular leaps and bounds, although such events are best remembered and most likely to be recorded in our histories. Rather, totalitarianism generally creeps. Self-censorship is one of the primary methods by which totalitarianism creeps in and flourishes. We would not agree to silence ourselves.

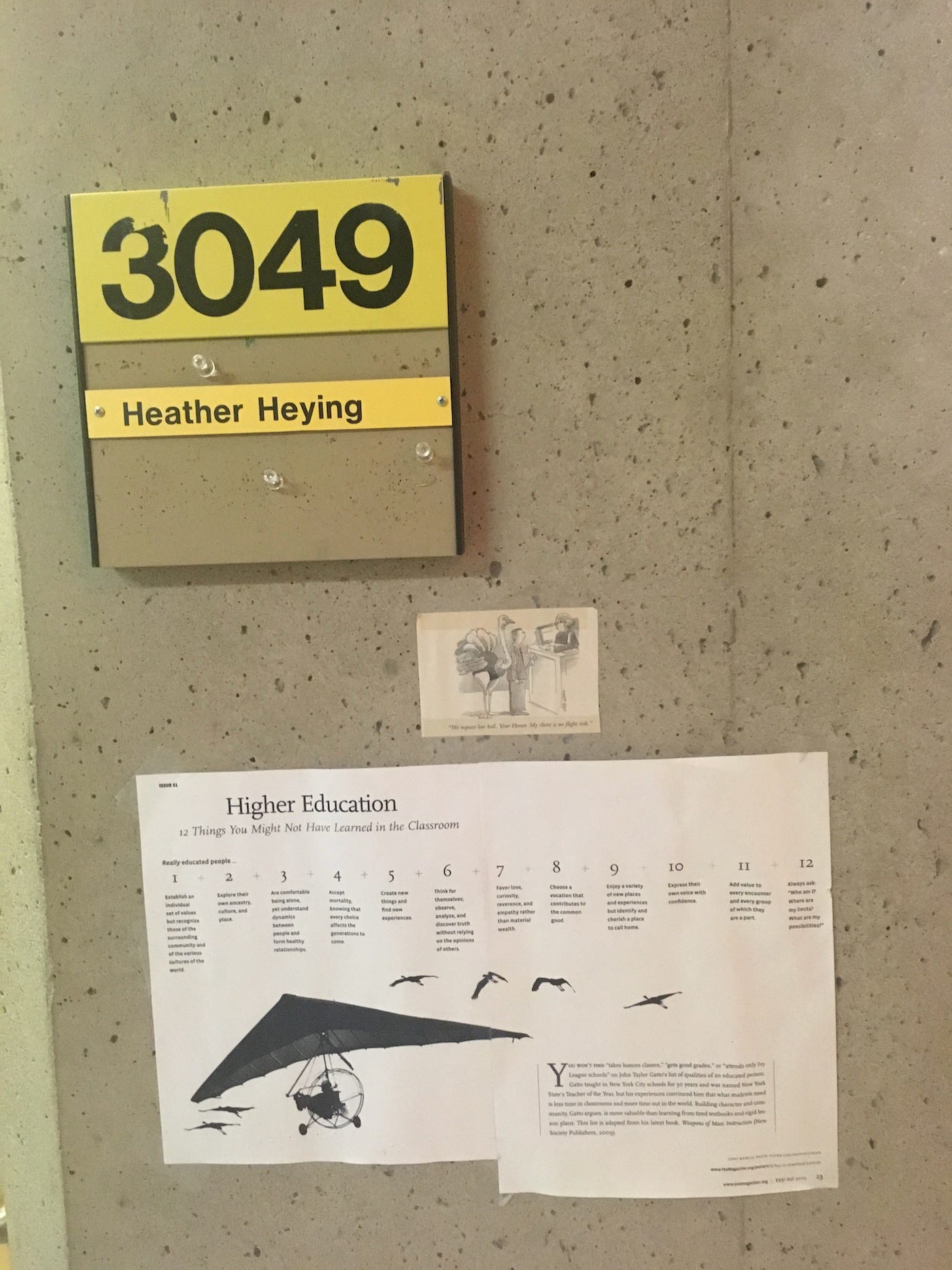

It was after midnight following a grueling day of mediation that we signed the settlement papers. For no discernable reason other than to twist the knife further, we were given just 48 hours to clear out of our offices. At the college where we had spent 15 years of our lives, where we were two of the most successful and popular professors, where our programs were often highlighted on the college’s website, and where none of our own students ever turned on us, we were given two days to clear out and turn in our keys, or have the locks changed on us, losing access to whatever we might have left behind.

I spent the next two days packing up my things, finding so much memorabilia along the way—notes and gifts from students, itineraries for domestic field trips and for study abroad, drafts of curricula for upcoming programs that now would never happen. I was filled with outrage, to be sure, but mostly what I felt was empty and shocked. I was in despair. How could an institution that I had loved and trusted so much behave this way? And how could it stand to betray its own students? Knowing that, within hours of handing in my office keys at the end of the week, I would also lose access to everything electronic at Evergreen, I wrote an email and sent it to the students in all of my past programs. Mostly, probably, the emails disappeared into the abyss—they went to Evergreen student email addresses that had largely ceased to exist. But a lot of them reached their mark. I know because I heard back from many students whom I had not heard from in years.

Here is the email that I sent:

September 13, 2017

Dear former students of mine at Evergreen,

Please excuse the mass email. I am writing to past students—many of whom I have heard from individually already in these past few months—to let you know a few things. Reaching out across space and time, in that tentacled way that modernity allows, and tapping you all on the shoulder. Remember when?

I am about to lose access to my Evergreen email, indeed, access to all that Evergreen is. When that happens, I will lose contact information for most of you. So I’m writing now, quickly, in boilerplate, to whole classes that haven’t been living, learning communities for many years.

Our learning communities were flawed, weren’t they, but they were rich. We had real disagreement, and discussion, and we learned, all of us. We also, usually, built trust. I am devastated to find your alma mater, the college that I have loved and called home for so many years, acting in bad faith, dismantling trust, shutting down dissent. I am, by turns, heart-broken and livid, and feel deeply betrayed by the college. But I have not regretted the work that I did there. It was worth it. You were worth it.

I loved being an Evergreen professor, in part, because it allowed for deep, personal connections with so many amazing, unique people. Perhaps you are skeptical—for one thing, you and 25-75 other people are reading these identical words, and that’s not counting all the other programs I’m writing to with the same words…but it’s true.

I have long held that the low bar that should be set for Evergreen faculty is that they a) fundamentally respect students as real human beings and b) have something real to offer, know something true about the universe. Apparently, it’s harder than it seems. It takes real time to have actual compassion for the differences that make us human, and the differences that reveal us as individuals—our varied developmental histories, our wounds and scars, our triumphs and confidences. And it takes some of the same compassion to not descend into tribalism, in which we judge each other on the basis of demographics.

Tonight I found myself having to clear my office, quickly, before my keys are taken away, and I found so many amazing reminders of you. The hand-written notes; the Dr. Pirandello doll5; the watercolors and pen-and-ink and wood cuts and other amazing art that you made for me; the molas from Panama; the picture of six of you, whom I will not name here, doing animal behavior, beautifully, while rowing on a lake in the San Juans. I was moved to tears. Most of you know me well enough to know, or at least to imagine, that I am not easily moved to tears. I still believe in the Evergreen model, and I know that it has served so many people so very well. Many of us have been enriched by the opportunity to learn in unexpected ways in community, in the field, in the classroom, in the lab, late at night after everyone else has gone to bed and there are just two of us, five of us, eight of us, talking, over a wooden table, or a fire, or a game of cribbage, or a guitar, in the Amazon, in Bocas, on the Oregon coast, in Sun Lakes.

[I then spent two short paragraphs advising former students how they might get in touch with me.]

I have fifteen years of Evergreen students whom I look back on so fondly, with gratitude and respect. Truly. Thank you for being among them.

-Heather Heying

your former professor

now, believe it or not, on twitter @HeatherEHeying

When I reread this email now, I am once again brought to tears. I still cannot believe it. I know that, given how it was possible for people and an institution to behave, it is better that I know. I would rather know who people are, and what they are capable of, than not know. And the people whom Bret and I now know, in the wake of Evergreen, are so abundant, and fascinating, and truly diverse across all of the usual dividing lines, demographic and otherwise. Just as in our classrooms for 15 years, we enjoy talking with and learning from people who are not like us: conservatives, for instance; and those with little formal education; and those who have deep faith.

My 18-year-old son Zack and I recently found ourselves in Warrenton, Virginia on a muggy Saturday morning. On the main road into town, there were competing protests: BlackLivesMatter on one side of the street, AllLivesMatter on the other. The BlackLivesMatter people look more like us—they look more likely to be eating locally-grown organic food, and finding pleasure in outdoor pursuits—but the ideology they are promoting is one that we have seen in full destructive glory in our hometown of Portland, Oregon, and before that, at Evergreen. Still, we probably see the world through many of the same lenses, and agree on issues like reproductive rights, and the urgency of protecting the environment.

The AllLivesMatter people reminded us less of ourselves in some ways, but that is not supposed to be a barrier to conversation among modern people. The AllLivesMatter protestors were on the side of the street that we happened to later be walking on, so we talked to a couple of them. They framed their objection to BlackLivesMatter with a religious lens, and quoted scripture at us by way of argument. I’m not any more compelled by actual scripture than I am by pronouncements from politicians or public health authorities who bark at us to #FollowTheScience without ever referencing any science. In both cases, rather than reason or our shared humanity being invoked, we are asked to put faith in an authority. I choose not to do that, or at least, to be highly cognizant of it when I see no alternative to doing so.

We humans, I am confident, have the capacity be good to one another while we logic our way through problems. I say that I am confident of that, but I admit that my confidence is flagging. The extraordinary breakdowns of rationality and decency at, first, Evergreen, and then during the Covid pandemic, have revealed more tears in the fabric of society than I had previously noticed. Once you see them, though, you can’t unsee them. Nor should you want to, should you be given the choice. Never choose the life of the lie.

Some but hardly all of the vast coverage of these events are here:

Writings:

Bonfire of the academies (Bret’s and my most complete version of events that we have put to paper, published December 12, 2017, in the Washington Examiner. No longer available on that site, so this link goes to another site that has reprinted it.)

The campus mob came for me—and you, professor, could be next (Bret’s op-ed in the Wall Street Journal May 30, 2017)

First, they came for the biologists (Heather’s op-ed in the Wall Street Journal, October 2, 2017)

On college presidents (Heather’s article in Academic Questions, Spring 2019, which is excerpted at the beginning of this post)

The coddling of the American mind (Lukianoff and Haidt’s excellent 2018 book which does a fine job of summarizing and interpreting what happened at Evergreen, among many other things).

Videos:

The devils of Evergreen State College (Mike Nayna’s three-part documentary on what happened at Evergreen, on YouTube, January 2019)

Let it all hang out: The Evergreen story (Benjamin Boyce’s 24-part documentary on what happened at Evergreen. Benjamin was a student at Evergreen when it blew up)

No safe spaces (feature-length documentary, by Dennis Prager and Adam Carolla, 2019)

Bret’s testimony before Congress, June 2018

My presentation at the Department of Justice, September 2018 (written transcript of published in Public Discourse, here).

Five years later, with Bret Weinstein (Benjamin Boyce and Bret talk about the five-year anniversary of the Evergreen blow up; I have not yet watched this.)

Excerpted from “On College Presidents,” my invited article for the journal Academic Questions, published Spring 2019. At the end of this post I have links to articles, books, videos, and films that explore the events in more detail.

Here’s one playlist, compiled by someone unknown to me or us, of some of the videos that emerged from Evergreen in May and June 2017:

In 2016, criticizing BlackLivesMatter was seen as clear evidence of racism at Evergreen, an event that I describe in my recent post, “If you don’t agree, you must be ignorant.”

I say “was” a black woman only because, far too young, she died soon thereafter.

About which, more next week.

Recently, I read “In Order to Live” by Yeonmi Park. The book is an autobiography by the young 22-year old, detailing her upbringing in North Korea, her escape, and her eventual refuge in America. She describes that when she was a child, her mother instructed her to censor what she whispers to anyone, anywhere, because the birds and mice would hear her and report what she says to North Korea’s benevolent leader, Kim Jong Il. My Canada and your America are no North Korea, that’s for certain, but when I read about Yeonmi’s childhood lesson, a conversation I had with a friend sprung to mind...

My friend and I were walking through a park, on our way home from our University campus in the fall of 2019. Our conversation ebbed and flowed, as usual. At one point, there was something secretive he wanted to share with me. There was no one in sight, but he glanced around to make sure that no birds or mice were listening. I glanced around too; what could be so secretive? In a hushed voice, he described a documentary he watched about a small American Liberal Arts College, somewhere far, far away, where rebelling students took control of the campus. They held the Administration hostage, and wouldn’t even allow the College President to go pee! They demanded the expulsion of a Racist Professor who dared to challenge the merit of an Equity agenda (Equity, eh?). I said to my friend, “that sounds ridiculous, that story cannot be true.” He insisted it was, and I knew my friend well enough to know that he is not the type of person to embellish a story for dramatic purposes.

BLM riots took centre stage in the spring of 2020. The claims of a Systemically Racist Society were the dominant theme, even here in Canada! Could this be true? Could my understanding of the decades-long march of Western Society towards increasing equality and tolerance be false? I was doubtful. The riots reminded of the unbelievable story my friend shared with me the year before. I asked him, “remind me, what was the name of that College where students held the Administration hostage?” It was the Evergreen College. Watching the Nayna and Boyce documentaries, I realized that the Everwoke meltdown was a harbinger of the BLM riots. More broadly, I began to recognize what social activism in the 21st Century had become: a collectivist mob assault on Western liberal values (Equity, eh?).

In the fall of 2020, I began studies in a graduate program. I became acutely aware of the DEI dogmatism deployed by my University’s Department of Spam E-mails; a constant stream of identitarian and victimhood pandering. Who dare criticize these undeniable subjective truths? Certainly not me. Over the past two years, in every exchange, I have been cognizant that the birds and mice might be listening.

However, through learning about Evergreen, I also discovered the DarkHorse Podcast and the Hunter-Gatherer’s Guide to the 21st Century. I am thankful, Heather, for the clarity and candour with which you and Bret tackle contemporary issues. Never stop!

Evergreen's loss is the world's gain. I am a conservative. I appreciate your Substack and the DarkHorse videos. Where I have disagreements with you and Bret I overlook it. You are entitled to your opinions as I am to mine. It is possible that all of us can be broadened by an appreciation of the other's viewpoint.

I do hope you two can get back to teaching at the new University of Austin.