I survey all that is mine: the lovely homes that I keep, in which my children are tended by their mothers; the landscape full of food and opportunities. Always vigilant, I keep a sharp eye out for intruders. There’s one now, creeping in along a back alley. I know him—that’s Frank. Sneaky little bastard. He looks like he’s on the make. I waste no time in launching my attack. I rush him, yelling and ready to fight. Frank turns tail and runs away. He always does. Now down off my perfect perch, I, Duncan, look around, satisfied at what I see.

But wait—what’s that noise? I hear another contender to the throne from nearby, singing. Singing. It’s Elliot. Of course it’s Elliot. The audacity. I go to the very edge of my property and strike up a song of my own. That should shut him up. But no. Elliot keeps right on singing, even swings into view with swagger and unearned confidence. I glare at him, look around my domain, as if to say: Have you seen all that is mine? Do you know who I am? How dare he.

Elliot keeps singing. Now he looks at me, and widens his stance a bit. What a dick. Dude does not honor the rules. Then he steps onto my property. So I attack him. Obviously. We go at it belly to belly for a while before I twist him and climb on to his back. I ride him around while he tries to dislodge me, and finally he throws me. Enraged, I chase him up a tree. He’s fast and strong, but this isn’t his tree, he doesn’t know it very well, and besides, I’m the boss around here. I chase him out on a branch and he loses his footing, hanging on by one arm for a second before plummeting to the ground. He begins to run away but I’m not done with him so I leap off the branch myself.

As I give chase on the ground, I notice Wanda, one of my children’s mothers, is watching from the sidelines. I just know she’s impressed. I pursue Elliot over hill and dale. We wrestle some more, and this goes on and on and on and on. I yell at him, but he yells right back. Until finally he doesn’t. He is cowed. He slinks back into the territory that is his, so near to and yet so very distinct from mine. I sit back, pleased with myself. Showed him.

Unbeknownst to me, while I was fighting with Elliot, Frank slunk back in, muttered some sweet words to Wanda, and got her into bed with him. What the actual hell. A top male has to be so vigilant around these parts.

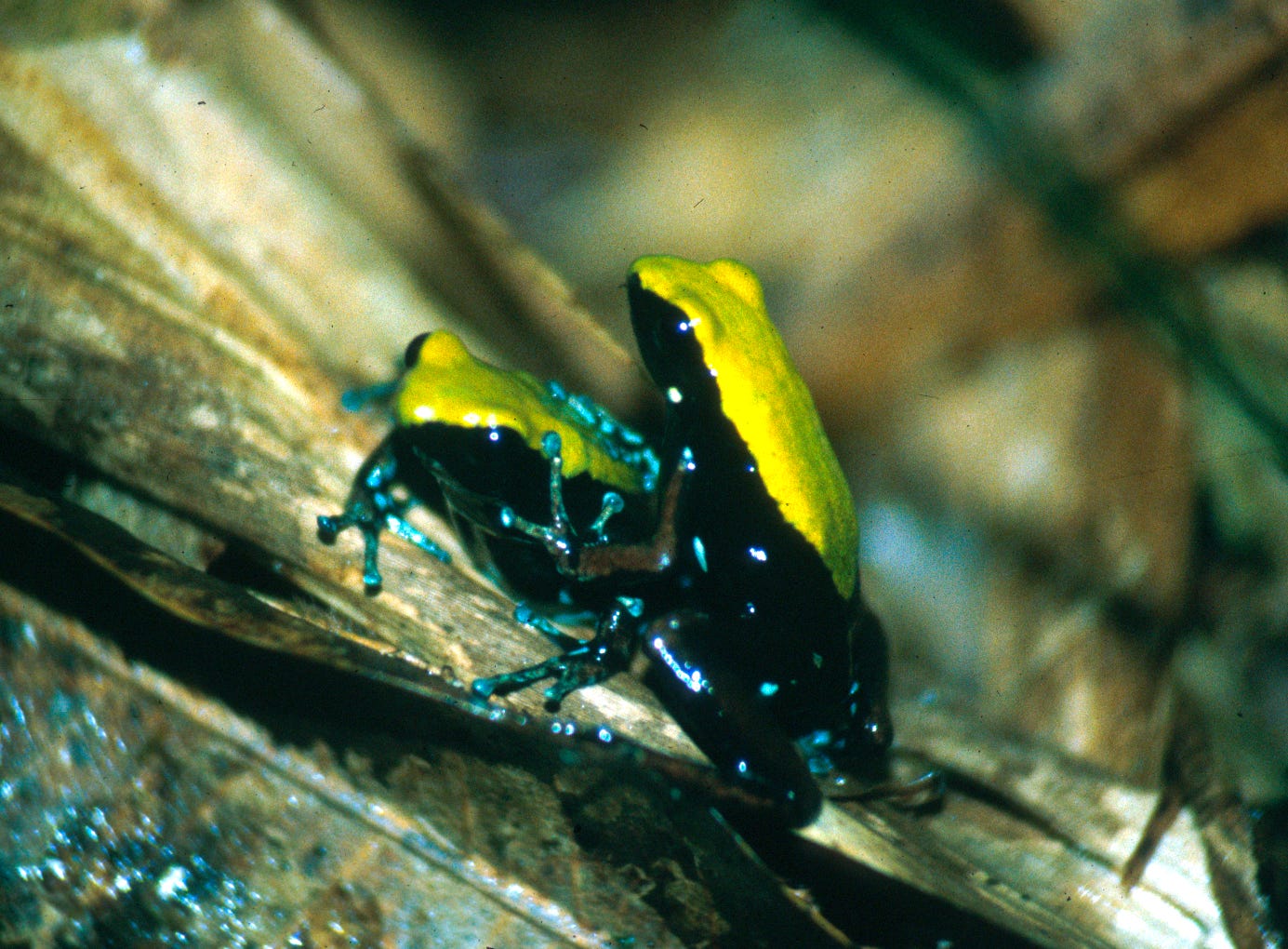

Nosy Mangabe lies in the northern reaches of the Bay of Antongil, off of northeastern Madagascar, in the Indian Ocean. Nosy Mangabe is a small green island, although in Malagasy, Nosy Mangabe means big blue island. I lived there over the course of two long field seasons in the mid to late ‘90s, studying the poison frogs there. I also spent time with lemurs and chameleons and leaf-tailed geckos, slept in a tent, showered in a waterfall, and ate mostly rice. The story above is an anthropomorphized account of one piece of what I learned there1. Here is just a little more:

Many of the frogs—Mantella laevigata2—are highly territorial, with males defending the limited resource that is water-filled bamboo wells. The wells are valuable because they act as defensible nurseries: during a successful courtship3, a female deposits an egg into a well, and the male with whom she is in courtship fertilizes it. The male, if he is the territorial owner of that well, attempts to defend it and the baby inside against intruders for the foreseeable future. Intruders include gigantic frogs of other species that like to use the wells for their own purposes, as well as craneflies whose larvae prove to be far more dangerous to the littleMantellas. And the female will return to the well after her egg hatches into being a tadpole—if her egg makes it that far—to feed her own unfertilized eggs to her child, for him to eat.

Because these wells are the key to the frogs’ reproductive success, and therefore to evolutionary success, any male who can successfully defend a good well4 is a successful male. Some males can pull this off, and more. They become like Duncan in the story above: holders of territories that include at least one, and sometimes several, good wells. The more wells in a territory, the vaster it is. Vast is a matter of scale, though, as these frogs are tiny, so even the largest territories comprise little more than a few square meters of forest floor. The Duncans of Mantella world are always vigilant, combative when pushed, and—I am told by both the Duncans and the females in their sway—extremely sexy.

A male who can defend a piece of real estate, but only one lacking the prize possession—a good well—is like our Elliot: a bit more sure of himself than is perhaps warranted, always testing boundaries, and often picking fights, most of which he will lose. And yet Elliot-strategy males do successfully defend territories, and they do it with care and tenacity. An Elliot’s territory tends to be adjacent to the territory of a Duncan, and along those borders there are frequent skirmishes. And the children of Elliots—which do exist, albeit in lower numbers than do the children of Duncans—tend to grow into successful young frogs. That is, if they can avoid the trials and tribulations of life in the jungle, like being eaten by a terrifyingly voracious insect larva, or—rather less of a risk—being squashed to death by the giant ass of another species of frog. Elliot-strategy males are also always looking for opportunity, roaming outside their territory frequently, but usually returning home no richer than when they left.

(A note on terms: Duncan-strategy and Elliot-strategy males have both territories and home ranges. Every mobile animal on the planet is said to have a home range, which includes all of the places they ever go. You have a home range, as does your dog, as does every baboon, cuttlefish, and dragonfly on the planet. A territory, in contrast, is that fraction of an individual’s home range that is actively defended against others of one’s kind (and sometimes, against others of other kinds). Not everyone defends some part of their space, however, so not everyone with a home range has a territory.)

So we have Duncan-strategy males, who defend resource rich territories. And we have Elliot-strategy males, who defend territories that do not contain limiting resources. And then there are the Frank-strategy males. For reasons that presumably vary, they don’t hold down territories at all. I suspect that they can’t hold down territories, but there is no way to know that for sure. What I know is that they don’t. But that doesn’t mean that they have given up on the reproductive game.

While the Duncans of Mantella world are yelling all the time (and the Elliots are doing so occasionally) about how great they are—singing, if you will; calling, more accurately; vocalizing, most technical of all—the Franks don’t make much noise. They skirt around the edges, waiting for opportunity. They wait for the Duncans to be defending their territories against someone else, their backs to be turned, or the Elliots to be off scouting new lands, leaving their territory undefended—and then the Franks come in and court any female who will have them. Sometimes—rarely, but sometimes—the Franks are successful in this endeavor, and a fertilized egg ends up laid in someone else’s well. And if the territory owner doesn’t recognize what has happened, he will end up raising a Frank’s child. It’s a win for Frank, even if the life he lives can look tenuous and unpleasant by comparison to that of his more successful compatriots.

There is no exact analogy between the strategies of these male frogs and that of men. That’s not the point. The point is this: There are three distinct male strategies in male Mantella laevigata. I wasn’t expecting that when I first began observing them, trying to untangle their natural history and mating system from a blur of activity that no human had previously tried to untangle5. I wasn’t expecting it, but it’s what I found. Three distinct male strategies. Not three distinct sexes (or rather four, once we include females).

Many species have multiple morphs—that is, distinct forms that individuals within a sex might have. White-throated sparrows are one such example, in which both males and females can be either “tan” or “white,” which refers to the color of stripe on the crown of their heads. The color descriptions obscure the fact that the different morphs also differ in behavior. White males are more promiscuous and aggressive than their more monogamous tan counterparts. White females are, similarly, less nurturing than their tan counterparts. In these particular birds, the genetics behind their morphs renders matings between same-morphed pairs largely futile—there are almost no offspring from white-white or tan-tan couplings. Thus, white males prefer tan females, and vice versa; and tan males prefer white females, and vice versa6. (Although white males, being particularly promiscuous, might try to mate with an old shoe if it showed up. They are really not choosy.)

This remarkable (and remarkably well-studied) system in white-throated sparrows thus produces the unusual situation in which any given male can successfully mate with only a fraction of the available females. The same is true for females looking to mate—a sizeable fraction of males are just not going to work out. This is fascinating, and unusual, and remarkable, and lots of other adjectives I have not yet used, but what it is not is evidence that these birds have four sexes.

Might we say that they have four morphs, then? I suppose. But what is really going on is that there are two morphs, each of which manifests differently—although not entirely differently—in each of the two sexes. I prefer this admittedly less pithy description, because it highlights the relationship between two variables: sex and morph. Much of what has been written in the popular press about these birds has, instead, conflated morph (and strategy) with sex, and some people have thus come to the erroneous conclusion that these birds have four sexes7.

They do not.

Morph is itself a somewhat complicated term in these sparrows, as it refers not just to the distinct plumage that is caused by genetic differences, but also the distinctions in personality and behavior that are downstream of the same genetics.

Sex is a less complicated term, however. Sex refers to the type of gametes you produce8. In animals, the choices are two: eggs or sperm. If eggs, then female. If sperm, then male.

There is a lot downstream of the sex that you are—how you look, how you behave, what foods you like, what kinds of things interest you. You cannot change your sex, but you can change a lot of things that were impacted by your sex during development. And some of them change without your willing it. As you age, your tastes and desires will change. As you learn new things, or meet new people (or frogs, or birds, depending), you may find yourself drawn in new directions. Those new directions do not change your sex, though, even if those new directions have you interested in and doing things that are more usually associated with the opposite sex.

Ben Appel has written beautifully about his experiences growing up gay before he understood quite what it meant, in a piece titled Homophobia in Drag. After falling in love as an adult, and crusading for marriage equality, Appel came to understand what he was working towards9: “I wanted to help create a world in which feminine boys and butch girls could exist peacefully in society. A world in which gender-nonconforming people were accepted as natural variations of their own sex.”

I want that world, too. Indeed, I expected it. The world that I came of age into, in the 1980s, was becoming that world. I had all sorts of “boyish” interests and tendencies back then (still do), with my fast driving and rough-and-tumble play, my love of math and sport and adventure. But nobody ever told me that I must therefore be a boy. We were beyond such prejudices. Just as the distinct morphs in white-throated sparrows, and the distinct strategies in male Mantella laevigata, don’t make them unmale or unfemale, or some new sex entirely, so too do the less common behaviors of boys and girls, men and women, not magically turn them into the sex that they are not. We are a sexually reproducing species, with two and only two sexes. There are as many ways to be a man as there are men, and as many ways to be a woman as there are women. Be you, be awesome, and embrace reality.

PostScript: With regard to the frogs, some readers may be wondering, what about the females? Surely they’re not all in lockstep, behaving exactly the same way? I agree—surely they’re not. But while males, even Frank-strategy males, have relatively small home ranges, females roam widely. I marked as many frogs as I could10, and I would then reliably see the males, day after day, usually within feet of where I had marked them. But the females would disappear for weeks. Then they’d show up again, sometimes two kilometers away in a different well-rich part of the forest, and hang out for a few days there, before disappearing again. Because females are roamers in this species, I know much less about the differences between individuals than I do about the males.

If you want to learn more, here are three ways in, from least technical to most: 1. Antipode: Seasons with the Extraordinary Wildlife and Culture of Madagascar. Published in 2002, this is my book for a wide audience about my life and research in Madagascar. Out-of-print, but at the link you can find some excerpts (but not about the frogs), and there are some copies still floating around out there. 2. Social and reproductive behaviour in the Madagascan poison frog, Mantella laevigata, with comparisons to the dendrobatids. 2001 Animal Behaviour journal article detailing the natural history observations that I made during my dissertation research. 3. My PhD dissertation.

I know that most non-biologists find scientific names cumbersome and a bit ridiculous. Often, I defer to those considerations, and use common names, at least when they are clear and unambiguous. But this frog is so little known outside of the pet trade and my research (and increasingly, zoos) that I never became accustomed to its common name—the climbing Mantella—so think of it, always, as Mantella laevigata.

Many Mantella courtships are not successful, and the primary reason that a female will call off a courtship is that the well that a male has taken her to doesn’t meet her standards of being a good well.

What makes a well a good well? I’m so glad you asked. Among other parameters, good wells contain abundant, clear water that is surprisingly acidic, they don’t leak, and they don’t have prior inhabitants, especially if those inhabitants are other Mantella eggs or tadpoles, or larval craneflies, which adore the taste of Mantella eggs. There are longer answers here and here (chapter 4).

Before anyone gets their panties in a knot about my Western science bias, so obvious due to my claim that nobody has tried to understand the natural history of these frogs before me, I will say this: The small group of naturalist guides who lived in Maroantsetra, the town on the “mainland” of Madagascar that is closest to Nosy Mangabe, were intrigued and excited to learn what I was learning about these frogs. They knew that the frogs existed—they are brightly colored and beautiful, if tiny—but the Malagasy guides did not know anything about them. Indeed, they knew nobody who did, and had no ancestral stories of such knowledge either. The Betsimisaraka—the particular tribe of Malagasy who live in this part of Madagascar—are, like most Malagasy, animists who actively worship their ancestors, disinterring some of the elders’ bones every year to inform the elders of what has been happening, so the lack of stories from those ancestors suggests to me that the knowledge had never existed.

In technical language, the preference for the morph that you are not is “near perfect disassortative mating among morphs.” – from Tuttle et al 2016. Divergence and functional degradation of a sex chromosome-like supergene. Current Biology, 26(3): 344-350.

The confusion resulting in the conflation of sex with morph was published in Audubon.org in 2017 (“almost as if the White-throated Sparrow has four sexes”), which was then further misunderstood by the Editor-in-Chief of Scientific American in a tweet in 2023 (“White-throated sparrows have four chromosomally distinct sexes….Sex is not binary.”).

To be more precise, females are individuals who do or did or will or would, but for developmental or genetic anomalies, produce eggs. For males (if you’re an animal), it’s sperm that you produce. But really and truly, the sophists can stop their dangerous intrusions into reality with “Oh-ho! So what you’re saying is post-menopausal women aren’t female! And six-year-old boys aren’t male!” Here is a longer discussion of what a woman is, which includes how we define that term’s three constituent parts, adult, human, and female.

Appel provides these as examples of what he would be working towards as a gay activist, but I disagree with the framing (it’s the only thing in his excellent piece that I disagree with). While it is true that many gender-nonconforming children will turn out to be gay, there are also many gender-nonconforming children who do not turn out to be gay. I was one such child, and I am hardly alone. Thus, I would argue that working towards “a world in which gender-nonconforming people [are] accepted as natural variations of their own sex,” strikes me as a humanitarian project, not a gay one (or a feminist one, for that matter, although when I was growing up, it felt like a feminist issue).

Marking small frogs for behavioral observations turns out to be an adventure unto itself. First, I tried giving them tiny, uniquely beaded waistbands, but the belts were either too loose, and fell off, or too tight, and impinged the movement of the frog. I thought about necklaces of the same construction, but frogs don’t really have necks. I did toe-clip the frogs—the somewhat barbaric practice of snipping the ends off a unique combination of fingers and toes—but you can’t see toe-clips at a distance, which makes it impractical for behavioral studies, and also? Their toes grew back! Ultimately, I landed on a solution that sounds more hard core than it was, although I will admit that sometimes, while I was sitting in the jungle on a folding stool with a small poison frog on one slightly blood-spattered knee, battery-operated tattoo gun in my dominant hand, ready to go, I did feel pretty cool. I never gave the frogs “Mom” tattoos. Instead, they got boring alphanumeric codes: A1, B2, etc. And by the end of the five-month field season in which I tattooed my frogs, the tats, too, were fading.

"While it is true that many gender-nonconforming children will turn out to be gay, there are also many gender-nonconforming children who do not turn out to be gay. I was one such child, and I am hardly alone."

Thank you Heather for taking a moment to include this bit. There is such a seemingly huge focus on the side of those pushing back against the "affirmative care" movement of children who claim to be trans, that if left alone, these kids will just grow up to be gay. But like you said, there are so many who aren't gay and simply just prefer hobbies more popular among the opposite sex.

I'm a millennial and was a tomboy growing up, and had loads of more male-dominated interests (hot wheels cars, classic rock and metal music, sports, hated dresses, action movies, most of my friends were guys, I took wood shop in HS). As a preteen and teenager I wore mostly sweatpants and hoodies to hide my body so I wouldn't get any attention from guys (didn't help that I started going through puberty on the younger side), and once overheard my dad asking my mom if I'd mentioned anything to her about maybe being a lesbian.

But fast forward and I'm married with 2 kids and the majority of my hobbies are still more masculine with the odd more feminine interest as well like cross stitching. I wish we could reclaim the tomboy label so that girls who aren't interested in stereotypically femnine things aren't automatically assumed to be either trans or lesbian.

Without ignoring the central message, the biology is fascinating.