I wrote this in 2018, and posted it on my Patreon. It seems, in some ways, to come from a different era. I have made a few minor edits for Natural Selections, but otherwise it remains as I wrote it then. It includes a suggestion that I would not make today; long-time readers will likely have no difficulty finding what I’m referring to. Paying subscribers can, as always, tell me what they see in the comments.

Travel is mind-expanding. It stretches perception, shifts the horizon, opens doors that you didn’t know existed, and allows for reflection of the value and wonders of home that perhaps you had become blind to. Some of the most unforgettable travel moments are only so in retrospect. At the time, peak experiences can be brutal. But not all of them are.

Disclaimer: This is not medical advice, nor should it be taken as such. What is written here is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

You are responsible for your own choices. In a litigious culture such as that of the United States, you can safely assume that rebar at eye-level and chasms in the asphalt will be marked and fixed as soon as possible, and that playground equipment and balconies will not break free and send children or partygoers crashing down. You are less likely to get hurt wandering around in the U.S. (or any WEIRD countries), than if you were to do so in Madagascar, say, or Ecuador, two countries in which I have spent significant time.

It is safer, therefore, in WEIRD countries. People can wander around foolishly and have a low chance of getting hurt. By “foolishly” I mean such things as being incapacitated from alcohol, or being so socially focused that you do not pay attention to your surroundings.

This safety that we have in the WEIRD countries, it comes at a cost. Being able to wander around foolishly is part of what has created generations of people who are a little bit scared, and somewhat confused, and quite lacking in experience. Travel is experience. But only if you dive in and let the tides take you, knowing that sometimes, rip tides happen, or rogue waves, or worse, and danger can be a learning experience and provide an ecstatic high, or it can be deadly. And it’s not always possible to know which ride you’re on.

Now I’ll make a few more enemies, and explain what I don’t mean by “travel.”

Going to Disneyland is not travel. That one’s easy. Disneyland is a fantasy and may well be a necessary tonic and a joy for many people, but it is not travel as I mean it. Any escape into a constructed universe that could be anywhere on the planet—also on this list: Las Vegas—is, by my rubric, not travel.

Going to Club Med is also not travel. (Full disclosure: When I was 18, my family and I went to one; my memory is hazy. It was the first and last time that any of us did so.) On a map it appears that you have traveled, but inside the compound of a Club Med, all is scripted and conforming to the cultural and social norms of the place you left. This is also not travel, in the sense that I mean it.

One step further: Going to Cancun or its immediate environs does not appear to be travel, either. I could tell many stories about Bret Weinstein’s and my adventures traveling through the Yucatan (and on South, all the way through Costa Rica) one Summer when we were young, and our shock at how the eastern Yucatan had changed when we went back with our children at the end of 2016. We were able to escape the gringo tourist hordes by going inland and south towards Belize, but the local culture had all but disappeared. American dollars (including ours), and the promise of more, has wiped out most of what made the Caribbean side of the Yucatan extraordinary, except for the climate and some straggling aspects of nature.

If travel is about new experience, the discomfort of travel should be expected. You don’t need to relish the discomfort. But “getting outside your comfort zone” will be…uncomfortable. If everything that you see, hear, smell, taste, touch, think and do while traveling is something that you were able to fully prepare for with advance research back home, then really, what is the point? If you are traveling in order to document the fact that you traveled and to post that documentation on-line and thus create and curate a representation of your life that others may look at and swoon over, there is a good chance that you do not have memories of the travel itself, but only memories of the documentation. (This is a topic for another time, but I also feel strongly that even the most creative and technically skilled photographers should put their cameras down sometimes and have experiences without consideration of how they will look through a lens.)

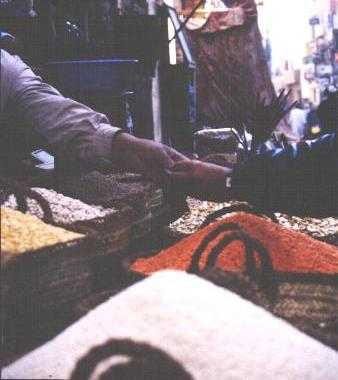

Now that I have probably struck a nerve, or three, with most readers, I will address the topic at hand: Why you should eat street food when you travel. (But first, one more time: I am not a medical doctor, and I am not dispensing medical advice.)

As I see it, there are two broad reasons to eat street food when you travel, the first cultural, the second biological:

1. Eating food that is cooked and eaten by local people offers a portal into their culture. Be appreciative, kind, and generous, and demonstrate that you are not just respectful of but actually enthusiastic about the food and history (architecture, myth, science, art, religion, sport, language…) of whatever place you are in, and you will find local people who will interact with you, if that is what you want. Once you end up in conversation with people, whole worlds open up. (To that point: I was once invited to a turning-of-the-bones ceremony in Madagascar, in which the ancestors are disinterred so that the village elders may tell them of the goings-on since last they spoke.) And this can happen almost no matter how little you know the local language. You do need to demonstrate that you are making an effort, however—that goes a very long way. Show up as the ugly American who repeats themselves loudly in English when people don’t understand you, and neither your food, nor your trip, will be very interesting.

Another way of putting this point is: Eating what the locals eat is actually experiencing their culture. That is travel. And the food is often extraordinary. Not always, but often. You won’t get molecular gastronomy at a street cart, but if that’s what you’re looking for, my advice isn’t for you, at least not on the topic of food. In the broad category of street food I’ve had while traveling, there have been perfectly grilled meats (on the bone, and in tacos, and as kebabs); vegetables whose names I don’t know and whose flavors reminded me of something I couldn’t quite put my finger on; fruits with mesmerizing colors and aromas; beignets and cheese, steamy soups and tomato salads, pancakes both sweet and savory, and a local rotgut that I think was taking the varnish off the table in real time. I’ve also had deep fried beetle larvae, and if that’s your thing, terrific, but it doesn’t turn out to be mine.

2. Your gut microbiome can change, and the sooner it mirrors that of the gut microbiota of the people around you, the more likely you are to be healthier, happier, and better able to enjoy not just the delicious local cuisine, but also everything else that you have traveled to experience.

Your gut microbiome responds to diet (easily digestible NYT version; and the original research: Collins et al 2018). The make-up of your gut microbiome has effects on sleep and hypertension (Durgan et al 2016), and obesity (Turnbaugh et al 2006), among other things.

Twenty or so years ago, we thought that we were singular, made up entirely of human cells. Maybe we granted that there were some mites living in our eyelashes. In stark contrast, current thinking suggests that, in a living adult human, there are more cells of foreign organisms—the microbiota, consisting of bacteria, viruses, and eukaryotes—many of which live in our guts and help us digest and process our food, than there are human cells. Clemente et al 2012 wrote an excellent review, and here is the beginning of an abstract of another terrific paper on the subject (Chow et al 2010):

So: When you travel, you can try to be a sterile being, ignoring the reality that you already contain multitudes of foreigners within you. Or you can embrace your new environment, cautiously approach new and interesting cuisine, expect to get some GI distress for 24 – 48 hours, and then find yourself, on the other side of that, able to enjoy everything about your new locale more fully, now that you are more of it.

If you are only going to be in a place for a day or two, and you know that you have a very sensitive GI tract, you might opt to take the sterile route, to keep yourself free and clear of the local microbes until you land somewhere for a longer time.

You should, if you are in the privileged position of being able to travel to places that are very different from the one you call home, and especially if those places are in the tropics:

Get fully vaccinated;

Take malaria prophylaxis if that is called for where you’ll be;

Modify your behavior to limit exposure to the vectors that cause many tropical diseases (I’m looking at you, Anopheles mosquitoes); and

Have a course or two of antibiotics on hand that you can treat yourself with if you absolutely need to, especially if you are in very remote places. Do not take antibiotics unless you are in real distress and far from medical help. If you do take them, make sure to take the entire course. And if you still have them at the end of your trip, donate them to a local medical clinic, where they can do some real good.

I do all of those things, and I eat street food with something like abandon. I do not require of the vendors whom I buy food from that they wash their produce in bottled water, or that they throw out meat that has been sitting in the sun with flies on it. That’s the kind of advice that you will get from others, and following it will mean that you have a lower chance of getting a very nasty intestinal bug. Eating street food has risks, and it’s not for everyone. You can’t predict what all will happen if you do so—in that lies some of the risk, and also opens the possibility for transcendent experience.

References Cited

Chow, J., Lee, S. M., Shen, Y., Khosravi, A., & Mazmanian, S. K. (2010). Host–bacterial symbiosis in health and disease. In Advances in immunology, 107, 243-274. Academic Press.

Clemente, J. C., Ursell, L. K., Parfrey, L. W., & Knight, R. (2012). The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: an integrative view. Cell, 148(6), 1258-1270.

Collins, J., et al. (2018). Dietary trehalose enhances virulence of epidemic Clostridium difficile. Nature, 553(7688), 291.

Durgan, D. J., et al. (2016). Role of the Gut Microbiome in Obstructive Sleep Apnea-Induced Hypertension. Hypertension, 67(2), 469–474.

Turnbaugh, P. J., et al (2006). An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature, 444(7122), 1027.

Velasquez-Manoff, M. (2018). Opinion: The Germs that Love Diet Soda. New York Times, April 6, 2018.

I tread lightly here because I greatly admire the author. Although I have always been a "fully vaccinated" traveler, I have re-assessed vaccines. Yet that is not why I comment.

On "Travelers' Diarrhea," even the CDC acknowledges that use of antibiotics shortens the course of sickness by 1-2 days. I'm pretty sure the CDC used to discourage antibiotic treatment for TD on the grounds that such use increases resistant strains. In any case, shortening TD by 1-2 days is quite a bit of time when one is traveling. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2024/preparing/antibiotics-in-travelers-diarrhea

Here's what I have long questioned: The admonition that we should always take the full course of antibiotics to avoid encouraging antibiotic resistance. I am not an evolutionary biologist. I am just a lawyer. Yet the "full course" dogma has never made any sense to me. In fact, I would think the opposite is true. It is taking antibiotics for too long that may encourage resistance. The point is lightly discussed here:

https://theconversation.com/doctors-may-be-prescribing-antibiotics-for-longer-than-needed-112609

Inspiration for the reassessment of "full course" dogma came from here: https://www.bmj.com/content/358/bmj.j3418

Then back to another piece supposedly refuting it here:

https://theconversation.com/why-you-really-should-take-your-full-course-of-antibiotics-81704

But the "persisters" argument about lingering bugs still doesn't make sense to me.

In the end I remain highly skeptical that one must take the "full course" of antibiotics to avoid increasing resistant strains of antibiotics. How do the persisters magically gain resistance if they would have only been killed had they been exposed to the compound that didn't already kill them?

If the argument is that we would be better off with fewer bacteria in the world, and less antibiotics means more bacteria, that seems silly.

I eat street food, but I have cast iron digestion from a very unsanitary childhood. My husband is usually more careful and wound up with amoebic dyssentery in Peru. The medical system that treated him was exceptional. Knowing oneself is important in this.

As for Las Vegas, it can be an adventure, just stay away from The Strip and the casinos. Incredible food and neighborhoods. I live about an hour away and I love adventuring there. Same for Los Angeles, I lived there 5 years and never went to Disneyland, but I went to Little Saigon, Monterrey Park, Korea Town, etc... So much adventuring to do there.

Tomorrow we are going to Querétaro and Friday we head up to the Sierra Gorda where people leave doors unlocked and I did not meet anyone who spoke English. There is an archeological park were locals walk their dogs. It has yet to be discovered except by locals who head up to escape the heat in summer. I had locally prepared food that was not "organic", they simply never stopped raising food the old ways.

I had a session with a local herbalist who about a half hour in told me how happy she was that I was not asking about hallucinogens. She said most Americans she talks to only want to get high. She told me about how no one in their community wore masks or got vaccinated and no one got very sick. They ate traditional food and took traditional herbs. Wonderful adventure.

I always eat indigenous food everywhere I go as it prevents illness. This was extra true in Lithuania where our Lithuanian friends were eating junk and got sick. We ate old school and were strong.