One year ago, A Hunter-Gatherer’s Guide to the 21st Century: Evolution and the Challenges of Modern Life, was published. In this book, Bret Weinstein and I apply an evolutionary lens to understanding modernity. Identifying hyper-novelty as perhaps the most salient feature of the 21st century WEIRD experience, we discuss everything from food, sleep, and health; to sex and relationships; to childhood, education and adulthood; to society-level problems. The book was meant to be something of a tasting platter: every chapter, and in most cases, every section within every chapter, could easily be a book of its own.

Hunter-Gatherer’s Guide made it to the New York Times best-seller list, despite being unavailable on Amazon for several weeks, starting three days after its publication date (“supply chain issues,” don’t you know…). We are grateful for the many readers it has had, and for the messages that we receive about the ideas therein. To celebrate the one year anniversary of its publication, today I’m sharing an excerpt from chapter 11, Becoming Adults. Tomorrow, for paying subscribers, I’ll post the “Corrective Lens” for chapter 11. At the end of most of the chapters of the book, we provided such a “Corrective Lens,” with advice on how to understand ourselves as evolved beings living in a world that is changing so fast, even we hyper-adaptable apes can’t keep up.

On the Benefits of Close Calls

“When I succeed, it’s due to my hard work and intelligence; when I fail, the system is rigged against me, and I had bad luck.” It’s easy to see the flaw here when stated so clearly, but most adults today are motivated by some version of it in their day-to-day lives. The fact that we tend to believe in bad luck, but not in good luck, makes it more difficult to learn from our mistakes.

When our sons experience setbacks—anything from dropping a glass to slipping on the stairs to breaking an arm— we ask them, “What did you learn?” We also, to their enduring irritation, will often ask them this when they almost drop a glass, don’t quite slip on the stairs, or narrowly avoid breaking a bone. They expect it from us now, but in general, both children and adults are incredulous when you ask this question after something has gone wrong. It can be taken as accusatory, rather than sympathetic, and sympathy is what we think we want in the aftermath of an accident or injury. As much as your currently ruffled feathers would enjoy being smoothed, wouldn’t you be a more productive and engaged human being if you could learn from what just happened, and thus decrease the chances that you’ll experience such a thing again? It is, as we say to our children, about the future. Trying to explain away the past, rather than learning from it and moving on, is a poor use of time and intellectual resources.

Having close calls is part of the set of experiences that are necessary in order to grow up. If your child has been made totally safe, living a life with no risk, then you have done a terrible job of parenting. That child has no ability to extrapolate from the universe. If you, as an adult, are totally safe, you are probably not reaching your potential.

What does “safe” mean, though? When we think about safety, it is tempting to develop a universal rule and stick with it. But this, like everything, is context dependent. Static rules are easy to remember; they are also of little use. Are roller coasters dangerous? Consider the risks of an adrenaline- pumping ride at an established theme park like Disneyland versus one at a carnival. Theme parks have permanence, and the rides have been in place for a long time; they are therefore almost certain to be safer than the frequently deconstructed and rebuilt rides of a traveling carnival.

Similarly, consider the risks of power tools. All blades that are powered by electricity are dangerous, to be sure, and require special attention and practice to be safe around. But if you think that “be careful, it’s a power tool” is a sufficient level of warning, you probably aren’t knowledgeable enough to be safe yourself. Consider band saws, circular saws, table saws, and radial arm saws: the hazard increases substantially as you move left to right through that list. You are far more likely to have a close call, rather than lose a finger (or worse), if you understand the different risks as you use the different tools.

Finally, consider the risks of a walk in a suburban forest in the United States, versus one in Yosemite, versus one in the Amazon. The risks from the environment are different in each case— other people are a far larger threat in a suburban park than in Yosemite, for instance, while physical injuries may be somewhat more likely in the Amazon and Yosemite than in a suburban park. The primary difference in risk to human health, though, is in the remoteness from medical care in a national park and, even more so, in the middle of the Amazon. As we used to tell our students in advance of study abroad, “Be courageous, but aware of your own limitations, and responsible for your own risks. Assessing risk is a different calculation when you’re far from medical help. Lawyers have not gone through the environments we’ll be traveling in and made them safe—in that truth lies both much of the fun, and much of the danger, of the journey.”

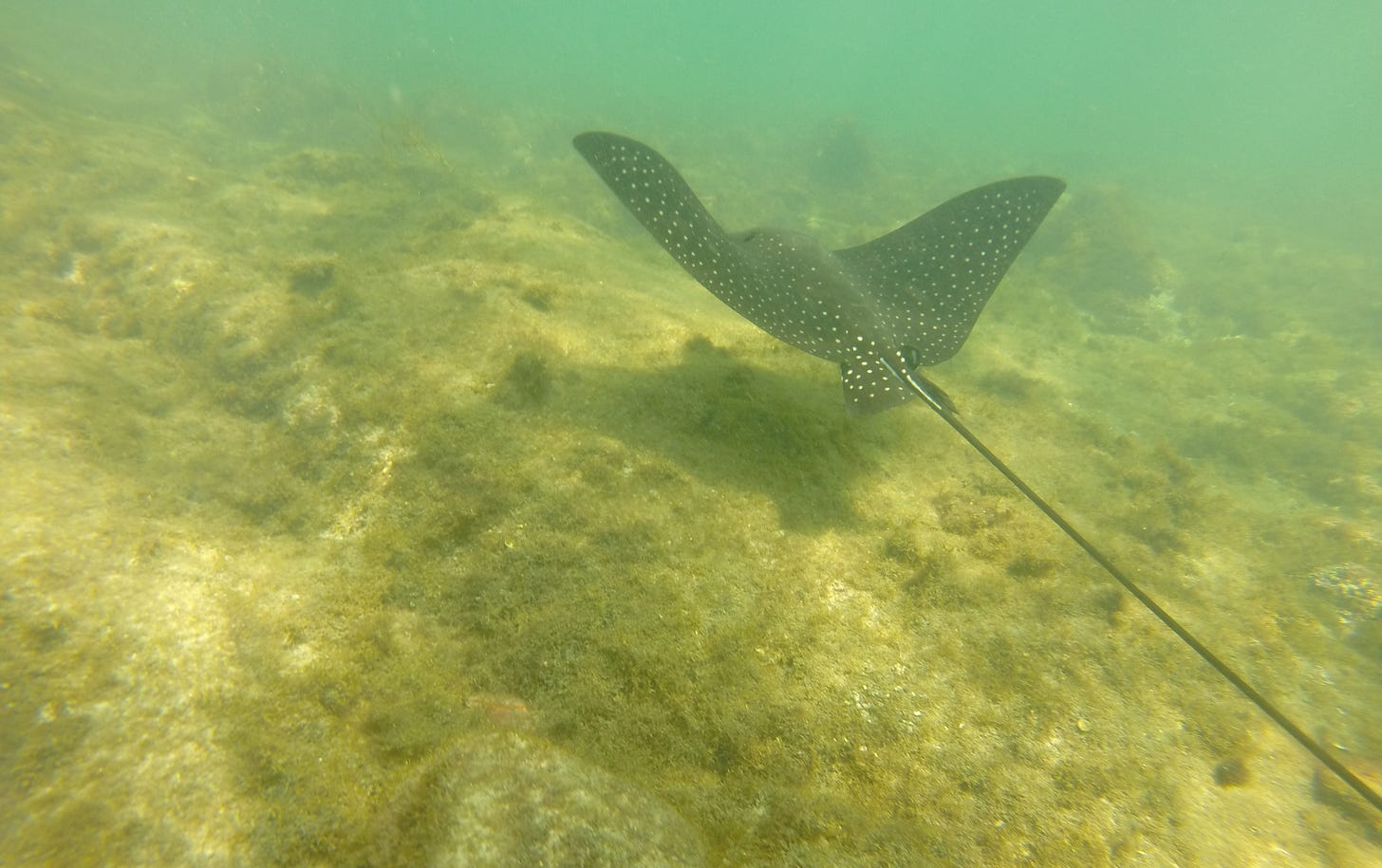

During our eleven-week study abroad trip through Ecuador in 2016, we had one primary and explicit rule: Nobody comes home in a box. We had three close calls on and just after that trip. You have already read about the tree fall. In the Galápagos a few weeks later, a remarkable boat accident nearly killed Heather and the captain, and could easily have killed all twelve of us on board, including eight students. It left Heather broken in many ways, nearly incapacitated, but she did not come home in a box. Our students Odette and Rachel were two of those in the boat accident: Odette sustained some injuries, but Rachel was, remarkably, unharmed. Together, they experienced the final close call, which was just half a month later. It was even more dramatic. It warrants a full retelling by them, but here is a précis.

Our thirty students had scattered to research sites to do five-week-long, independent research projects. Odette and Rachel had begun working at a field station in coastal Ecuador, but had gone to the nearest town to make the required weekly email contact with us and to celebrate Rachel’s birthday. They had splurged on a second- floor room in the Hotel Royal, which was the tallest building in Pedernales, six stories of unreinforced masonry. Just after they came in from watching the sunset, the room began to shake. They reached for each other and fell together on their knees between the two sturdy twin beds. Then the entire hotel collapsed—both under and on top of them. They were briefly in free fall, along with several stories of cinder blocks surrounding them.

That earthquake on April 16, 2016, was a 7.8 on the Richter scale. It devastated much of coastal Ecuador. Pedernales was at the epicenter and was largely destroyed.

We learned of the earthquake within an hour of it happening. We knew where all of our students were, and only a handful were in the danger zone. We quickly accounted for everyone— everyone except Odette and Rachel. We knew they had gone to a coastal city, which we believed to be Pedernales, for the weekend. The reports out of coastal Ecuador were grim. We talked to Odette’s mother several times, trying to reassure her, and to the people who ran the field station where the girls had been—we were assured that the staff who were accounted for were on the move, actively looking. Some of the staff were also missing. Bret began to make plans to go back to Ecuador to look for them. Heather could still barely move from her own injuries from the boat accident, but Bret could go. It wasn’t clear that it was the right move, but it was the only action possible, and we needed the girls to be all right.

Mid-afternoon of the following day, after twenty hours of hoping desperately for signs of life, we got a short, grateful email from Rachel. They were alive. They had salvaged almost nothing. But they were alive.

As far as we know, Rachel and Odette were the only survivors from the Hotel Royal. They fell in just the right place—between beds that had been so overbuilt that they withstood several stories of masonry on top of them—so they got lucky. Then their considerable wisdom and clear-headedness pulled them through what would be a nearly twenty-four-hour horror show.

They were trapped under and amid concrete rubble and dust, ghostly apparitions in the light of Odette’s tablet, which had somehow both survived and was findable by them in the immediate aftermath of the quake.

Aftershocks began shortly. The concrete slab over their heads moved slightly. They heard voices outside, and they shouted. Three men heard them, and together they all dug through the masonry with their hands, enlarging a tiny gap into one large enough for the girls to get through. Odette had considerable but not life- threatening injuries. As a ballet dancer, she was familiar with pain, but this was far different; she couldn’t walk. Rachel was, once again, unharmed.

They needed to get to Quito, but their journey was never simple. They were helped by many good people, and ignored or rebuffed by many who could barely take care of their own. In Pedernales, all was chaos. They saw a woman holding her lifeless child in her arms. They began to hear people murmuring about tsunami. One of their many rides out of town, which seemed promising, fell apart when the driver learned the fate of his family. While ensconced in another ride in the back of a utility van, a makeshift medic cleaned and stitched the long laceration in Odette’s foot, an injury that would later require more than one surgery to heal. One of their rides ran out of fuel. Another had to turn around at a missing bridge. Again and again they were returned to Pedernales, the scene of twisted concrete and sobbing people and a fine white dust on everything— in part, the remnants of the Hotel Royal. At last, having found seats on a bus to Quito, they encountered massive landslides from the earthquake that nearly blocked the road. As they edged past, chunks of earth disappeared into the chasm below.

Finally, they made it to Quito. They were alive, and they were safe.

Nobody came home in a box on that trip. And despite the extensive physical damage and psychological trauma she endured, Odette later said to us, “The trip was singular, remarkable, terrifying, extraordinary. Even if I knew everything that was going to happen to me, I would still go. It was so important to me.”

Buy A Hunter-Gatherer’s Guide to the Century everywhere books are sold. Now also available in Spanish and French; many more languages coming soon.

Thank you for sharing this excerpt and congratulations to both your and Bret on the one year anniversary of the release of the book!

"In praise of the close call" Nothing clarifies the mind and fixes the lesson into it quite as well as a jolt of fear-caused adrenaline. I have always felt that our "original sin" is that we so often have to learn things "the hard way" for those lessons to stick.