Antipode is a true account of my experiences while doing research in Madagascar from 1993 – 1999; it was published by St. Martin’s Press in 2001. You can start at the beginning with the Introduction, move into all of the chapters, and finish here, with the Epilogue.

Leaving Madagascar in 1999, I didn’t know when I might return. Our friends wanted to know if it might be next year, or the year after that? I couldn’t say. I had scheduled our departure such that by the end of April, on my 30th birthday, I would be back home. This was my birthday present to myself. By the end of that trip, though, I had finally fallen in love with Madagascar, and I didn’t feel the predicted urgency to leave.

Then Air Mad decided not to send the plane that flew between Maroantsetra and Tana, a flight for which we had had tickets for months. The plane simply didn’t arrive. Our international flight out of Tana was only 72 hours later. In the ensuing 24 hour dash to get out of Maroantsetra, we tried hiring a boat, a taxi-brousse, and even tried to charter a plane. A fast boat, we had heard, existed in town, captained by the mayor’s son, and perhaps he would take us. Heloise, the chauffer, took us to the weird outskirts of town where we had never been, dense with forest and broken down shacks. Here the son of the mayor lived on a small estate. He was a corpulent man surrounded by fawning women. He agreed to take us to Tamatave on his boat, for the astounding price of 5,000,000 FMG, almost $1,000. I didn’t have that kind of money with me. On the way back to town on the muddy rutted road, deep forest tangling in from both sides, we ran into one of the guides, who jumped into the Rover with us as we tore through town, trying to figure out what to do next. Perhaps we could hire a taxi-brousse.

There were no taxi-brousses equipped to make the long trip south, and besides, many of the roads were impassable at that time of year. We couldn’t count on reaching Tana in three days, even if we had found a vehicle capable of the trip.

Two vazaha who were staying at the new hotel had also been put out by Air Mad’s negligence, as they needed to get home for their wedding celebration. They had enough wealth to cover the fact that we didn’t, and when they chartered a plane, they told us that we could accompany them for far less than they were paying. It was due to arrive at six the next morning, and take off immediately thereafter, so we had to be there early or miss our opportunity. That night there were no rooms available at the Maroa, and our air mattress was packed away behind a locked door at Projet Masoala, so we spent a fitful, miserable night on the floor of the Projet, worried that we would somehow miss the flight, and be out of options.

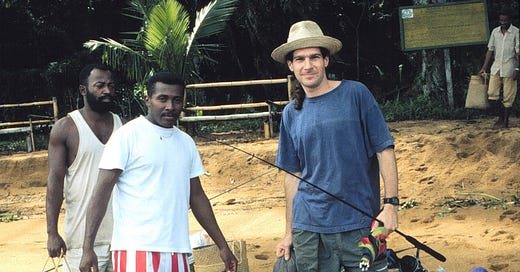

By morning it was pouring, sheets of water peeling off the sky, turning the still dark streets into pools. Heloise, who was going to take us and our stuff to the airport, was late. Very late. I went out to the main road in town, where he would be coming from, and looked vainly down the empty street. There were no signs of movement. I was wet, it was dark, and several miles out of town a plane would be touching down shortly, then leaving again. Bret went off to find someone, anyone, awake or not, with a vehicle who could take us. He found a man with a taxi-brousse—a tarp covered pick-up truck. We had spoken to him the day before, and though he couldn’t get us to Tana, the airport was within range. Taxi-brousses don’t travel anywhere with just a driver, so shortly he and his two men arrived at the Projet. We loaded the brousse up, and took off down the wet, rutted roads. Over the roar of the engine and the pounding of the rain, I thought I heard a plane engine. Was it coming, or going? As we pulled up to the airport, I leapt out of the back of the brousse where we were sitting, and ran around to the back of the airport, where the airstrip was. En route I plunged into a hole, submerging my leg up to the knee in cold, murky water. I continued on. Rounding the corner on the building, I arrived to see…nothing. No plane. No evidence of a plane. No other vazaha. It was seven o’clock now. Surely they had left without us. I stared in disbelief, frozen, until Bret and Glenn caught up with me.

“Where’s the plane?” one of them asked. I couldn’t speak. It was too tragic. We were never leaving, and I was destined to celebrate my 30th birthday on the floor of Projet Masoala, dirty and damp.

The driver of the taxi-brousse saw a man in a field nearby, and went over to talk with him. He came back to us and reported that the man had seen no plane this morning, that none had arrived. Then we heard the sound of another engine in the distance, not in the air, but on the ground. The rain was diminishing, but thick low clouds obscured line of sight beyond 200 feet. Suddenly the Rover was upon us, Heloise at the wheel, the two vazaha from the new hotel packed inside the cab. They were frantic, assuming that we had left without them, rather than the other way around.

“No,” we told them, “there has been no plane. It never came.” They were inconsolable. They would miss their own wedding. “Maybe it’s just late,” I suggested, “the weather has been bad, especially for a small plane.” So we sat, the five of us, listening for the sounds of a plane for the next two hours.

The taxi-brousse left, but Heloise sat a short distance away from us, looking despondent and pale. The driver that was supposed to ferry the other vazaha had never shown up, and when, desperate, they began roaming the roads outside the new hotel, Heloise had happened upon them as he was speeding by to get us, knowing he was hopelessly late. I approached him. He looked stricken.

“Is everything okay, Heloise?” I asked gently. He was trembling with what turned out to be a combination of fever and fear.

“I am so sorry I was late, Erika,” he said, his eyes downcast. “Please, please, I am very reliable, this is not something I do. I will be in big trouble for this.” He was sweating copiously on this chilly wet morning.

“Are you healthy?” I asked him. He looked up at me, imploring.

“I have malaria,” he said. “Today I am feverish, but that is no excuse…” I was aghast. Deeply afflicted with a serious illness, he was worried that we would be mad at him, and that for the sheer pleasure of being vindictive we might get him fired. If the vazaha makes a complaint, the vazaha is right. He would have no recourse.

“Heloise,” I said, touching his shoulder so that he would look me in the eyes, “this was not your fault. You are sick, and need to rest. We will not get you in trouble.” He looked relieved.

“Thank you,” he said, smiling, “thank you so much.”

“No,” I said, wanting to assure him that he had done far more for us than we had done for him. “Thank you, Heloise.”

We waited for hours, the five of us, knowing with more certainty with every passing minute that the plane would not come. We tried to assuage the mounting panic by going outside and peering into the sky, dark with cloud, or weighing ourselves on the large scale inside. Bret, Glenn and I had each lost 20 pounds, despite our constant attempts to procure peanut butter and macaroons to accompany our daily rice. We were almost skeletal now, our pants hanging loosely around us, held up only with fraying belts.

At 10:00 a.m. an official associated with the airport arrived. He stood around idly, disappeared for a while, then came back and announced to us that Air Mad was sending a plane. Where this news came from, and how the decision was reached, we never knew, but by six that evening we were back in Tana, with a whole day to spare. The chartered plane, so far as we knew, simply never came.

Madagascar was never a place that grew complacent, or felt satisfied that its visitors had really experienced all that it could offer. As I flew away from the big red island that final time, research notebooks full of data pressed close, I thought how difficult it would be to assess the broader Malagasy experience scientifically. Even in the small world of frogs and wells, intentionally constrained by my experimental designs in order to reduce chaos and uncertainty, I couldn’t keep the vagaries of Madagascar life under control. The weather wasn’t consistent, and the equipment often failed, or was whisked away by thieving hands. Still, I maintained enough control to obtain reliable data, to discern pattern in the frogs and their neighbors, to know that what I was seeing was real. What of my other experiences in Madagascar, though? What of the months of being followed, silently, by naked sailors? Or having a lemur remove a chunk of my arm? What of attending a retournement, and drinking toka gasy from banana leaves while the spirits hovered around the head of a sacrificed zebu? To interpret these experiences, I could not rely on formalized scientific protocol, or on repeated iterations of interactions, or theory. I had only observation, the strongest tool in anyone’s arsenal, scientific or no.

So ends Antipode.

I so enjoyed reading and listening to Antipode and appreciate you publishing it here. Your experiences illustrate ingenuity, compassion, and grit. I bet you manage a two hour delay in travel much better than most!

Thank you so much for making this available to us.