Antipode is a true account of my experiences while doing research in Madagascar from 1993 – 1999; it was published by St. Martin’s Press in 2001. Here is where we started—with the Introduction. And here are all of the chapters posted thus far.

On my first trip to Madagascar, when we were in the dry south, Bret and I wanted to see nature untamed. We had heard about a “private reserve” that promised snakes and forest and sifakas, so we signed up to go. Our guide was merely a glorified driver, with no ecological knowledge, and he took the two of us along an interminable stretch of road. We were watching the clock, thinking the road might be the extent of what we saw on this all-day “nature tour.”

Spotting a troop of ring-tail lemurs playing in the spindly, spiny native plants—reminiscent of Dr. Seuss, like so much in Madagascar—we grew excited, and asked the driver to stop.

“You don’t want to get out here. This is forest!” he exclaimed.

“Yes,” we agreed, confused at the implication. “And there are lemurs here. We want to see them.” The driver shook his head.

“Not these lemurs. These are no good.”

“Why?” we persisted. “There’s a whole troop—look, a baby on its mother’s stomach, and juveniles chasing each other. These are wonderful lemurs!”

“But they are wild,” he said. We were silent. “I’m taking you to better lemurs, lemurs that know people, and approach when you give them bananas.”

So this, like other reserves we had been to and were now avoiding, was to be a small plot of disturbed forest where friendly lemurs approached banana-toting tourists. As we were to find over and over again, few people trying their hand at ecotourism in Madagascar understand that some of us want to be immersed in nature, not carefully shielded from its betrayals and surprises.

Conservation is a tricky issue, especially in the developing world. White outsiders want to preserve the environment they view as precious, often without regard for the equally native and natural people who live in it. Ecologists and other trained scientists gain personally by convincing themselves and granting agencies that their work will benefit conservation efforts. Native peoples cannot fathom why the welfare of animals they might eat, or of trees, is more important than their own survival and traditions.

Why do we want to save the forests? Some would say because they are valuable, as potential harborers of undiscovered compounds, which might do humanity a public health service if found. But if we need justify all scientific inquiry on the basis of what specific, practical, benefit it will serve, we are lost. Our culture cannot claim foresight, nor intelligence, nor even a grasp of history, if we pursue only that which can be currently justified as useful.

If not for practical reasons, then, why do we want to save the forests? In part, because humans do not have the right to destroy them, though we have already destroyed so many in the developed world. We did not make them—indeed, they preexisted us, helped shape us into our current form.

But the emotional argument is perhaps the strongest: do we really want a planet without natural places? Are we content to lose all space that is free of human nattering and influence? As human culture homogenizes to a lowest-common-denominator across the globe, do we want to also eradicate what advertising and big business cannot get to? Nosy Mangabe has never been touched by Adidas or Nabisco or McDonalds. Even Madagascar is too small a market for them to be there yet. Coca Cola is there, in drinks with names we don't have at home, but their influence is relatively small. In 1999, the theme song from Titanic blared from every speaker in Maroantsetra. Luckily, Maroantsetra has very few speakers. There are a few huts in town where you can go watch a video on a certain night every week, the name of the film written on a chalkboard in front of the house. There is no television in Maroantsetra yet. Still, our Western influence is coming, albeit under a different guise.

The new hotel, the grand hotel, the Relais, opened in Maroantsetra in 1997. At the time, Maroantsetra had one wheelbarrow to its name, and when Jessica and I tried to commission it to aid us in porting our baggage and provisions to the boat, it had no wheel. Maroantsetra had, as its sole attractant for the vazahas, the proximity of Nosy Mangabe and the more isolated Masoala peninsula. And yet the hotel came to Maroantsetra.

It is debatable whether conservation should encourage tourism at all. It may be helpful to conservation efforts to spread the word about the beauty and diversity of ecosystems in the world, through interested laypeople with a fascination for nature. But should it be a stated goal to attract Westerners to preserved areas in the developing world? I believe so, for the following reasons: naturalist guides are required to show vazahatourists the forest. In general, naturalist guides are locals, and these people will, if they are good at what they do, have an interest in the forest, even a passion for it. Furthermore, if their welfare depends on being hired by vazaha to be shown the forest, they will come to respect and help to protect the forest. They will speak of the forest with fondness and care, to their families and friends. It will become clear to the community that protecting the forest brings money into town, and not just for the naturalist guides. The food vendors in the marketplace benefit, and the hotels, and the restaurants. The weavers who make baskets and hats benefit from our presence, for we buy their products. And the charcoal sellers, who sit at the bottom of the economic ladder among the vendors in the Maroantsetra zoma, they too benefit from us, for we must buy charcoal to cook our rice. Even the vazaha must eat. With tourists come an infusion of money into the local economy. In all of these ways, ecotourists, who come to see the forest, bring an economic bloom to the town of Maroantsetra. The townspeople can see, even if they do not understand why, that the attraction is the forest, and that without the forest, the vazaha would stop flowing, and so would the money.

But the introduction of a hotel such as the Relais de Masoala changes all of this. The Relais charges rates that are an order of magnitude higher than the other hotels in town—$70 per night, while the Maroa charges $7.50. If you stay at the Relais, their vehicle picks you up at the airport and ferries you through town without stopping— Maroantsetra passes by the window. You are delivered to their little haven, which has very little to do with Madagascar. All of the workers are dressed in odd, but specifically non-Malagasy costumes. No other villagers are allowed on the grounds.

Patrons of the Relais are discouraged from going into town. Why make that long, hot, dusty walk, where you might be obliged to interact with townspeople who share no piece of life experience with you, and may not even share a language. It will probably be frustrating, and perhaps even a little frightening, to have interactions so foreign to your expectations. The Relais successfully protects its patrons from ever realizing that Maroantsetra is filled with smiling, life-loving people. The Relais provides European meals, a full bar, hot showers, laundry service. And, for an additional fee, it offers day trips to Nosy Mangabe.

The Relais did not want to advertise Nosy Mangabe to its patrons. Access to Nosy Mangabe requires acquiring permits from government agencies, and hiring naturalist guides from their Association at Projet Masoala. The Relais is otherwise free from such restrictions. Monique, the owner, wanted to take tourists to the flat little deforested island that she had procured, where the Metcalfs and I had spent Easter two years earlier, rather than the lush rainforested island of Nosy Mangabe. But her tourists were having none of it. So she made a bid to take over Nosy Mangabe. The Wildlife Conservation Society has the interests of the forest, and the local people, in mind. Were the new hotel to take over Nosy Mangabe, however, those interests would be turned on their head. It would, I am certain, be the end of the reserve. Monique, and her Relais, are not mega-corporations. Because the new hotel is relatively small, it seems less dangerous. I believe it may be more so.

Before the Relais, the few tourists who came to northeastern Madagascar were ecotourists. People engaged with nature, wanting to see the results of millions of years of evolution in weird and fantastic forms, and willing to be somewhat uncomfortable to do so. The people Monique is attracting are wealthy tourists, adventurous enough to go off the beaten path to Madagascar, but unwilling to endure hardship to experience Madagascar as it really is. These people are probably aware that one of Madagascar's claims to fame is the extraordinary diversity and endemism of its biota. But these are not people awed by nature. They are tourists, not ecotourists, and by ensuring their comforts, and protecting them from interacting with the real people who live just outside the gates of the Relais, it is ensured that their preconceptions about the developing world will remain.

The Relais would turn Nosy Mangabe into a beach resort for wealthy vazaha. I have seen this before, in Central America. A façade is erected to look like home. Tourists hand over large amounts of cash for the pleasure of visiting the façade, and little of the money ever trickles into the local economy. Money would probably be poured into a more functional and beautiful plumbing system; into a kitchen that could prepare meals without charcoal smoke or rice; into easy walking trails. The Relais would probably begin feeding lemurs, to ensure close encounters for the tourists, so that nobody went home feeling they had not gotten their money’s worth.

Money would not be expended for the exquisite naturalist guides who have trained themselves so well in the ways of the forest, in languages, and in how to interact with vazaha. Already there were arguments over pay—the hotel did not want to pay the minimal rate the guides had agreed upon among themselves. Little of the money spent by tourists at the Relais went to the local economy. What value, then, does this new hotel have to local people?

If the new hotel administered Nosy Mangabe, the people of Maroantsetra would come to dislike the island, too. Once economic incentives vanished, there would be no reason to protect the forest. Even the guides, even Felix, with the most naturalist in him of all, he who loves to go into the forest even when his tourists do not, would have to find other work, or he and his young son Alpha would starve. Knowledge of the forest and its intricacies would die out in Maroantsetra. Ecotourists would no longer be attracted here, because the prices asked by the Relais are too high for most. Having one or two researchers hanging about to explain some curious natural history revelations to the fellow vazaha might be handy, and surely there are enough out of work Ph.D.’s to take that job, demoralizing and, indeed, destructive, as it is. For that job would take food out of the mouths, and knowledge out of the heads, of the local people.

Northeastern Madagascar, including the newly minted Masoala National Park, has more species endemic to itself than most countries. It contains the largest remaining piece of lowland rainforest in Madagascar, and is incomparable, and irreplaceable. It is at risk, because decisions are being made that put greater emphasis on impressing the wealthy than on protecting the environment. It is a deal made with the devil. The devil: money hunger from the west. Bring rich vazaha here while exploiting their desires for comfort, and there will be no returning. Pirates, a Dutch hospital, a Malagasy cemetery, Malagasy fisher people—all of these are part of this island's history, and all have left a mark, but none is indelible. The mark of Western money would never be erased.

Once the mark of Western comfort-driven consumption comes to a place, everyone believes that their lives, too, would be better if only. If only I had a tarp like hers. If only I had hiking boots like his. If only I had as much money as they do. With their longings, and an increasing availability of consumer goods, we will turn them into us, with our lost communities, our clans spread thin. They will forget to value what they have, and care only for what they do not. And in all of that cultural change, while the generous and real people of Maroantsetra turning to Western wannabes like the rest of the world, the forest will disappear. It will go quietly. A few people will notice. Nobody will heed the cries of despair. And then, it will be gone.

The new hotel was not the only risk to Nosy Mangabe. Lebon and Fortune had grown complacent in their jobs, bored with their lives on the island, so that even their large incomes (by local standards) weren’t incentive to actually protect the island they were being paid to protect. Before Rosalie left, she saw a sailor hunting lemurs with a spear. She had dissuaded the man, but when we alerted the conservation agents to the problem, we received only glassy stares in return.

The guides began reporting that Uroplatus—the magnificent, camouflaged leaf-tailed geckos—were declining on the island. They had reason to believe that the cause of this decline was that someone in town was paying 5,000 FMG for any that came their way. Less than one dollar each for one of the more spectacular lizards on the planet. Probably they were being whisked away to the first world, where a tropical herp enthusiast would pay in excess of $100 for that same animal, which had been ripped from its wild life. When we reported this probability to the conservation agents and their higher ups, again nothing was done. Several weeks later, a crate of Uroplatus was discovered being smuggled out of Maroantsetra on a plane.

For reasons I could never understand, when the guides generated plausible explanations for mysteries such as the dwindling Uroplatus population, they were not paid any heed. The guides, to a person, were tremendous—eager to learn, already possessing a good deal of knowledge, intuitive about humans and nature, amiable and fun to be with. By comparison, the conservation agents had become a hazard to the island, accepting kickback from sailors with spears.

The guides, like Rosalie, stayed optimistic and intellectually curious in the face of an uncertain future. Augustin asked me to make a list of the frogs I had seen, so he and the other guides could learn them. When he was out on the island with Hungarian tourists one day, and they wanted to play alone in the water with their snorkels (snorkels kept multiplying), Augustin went into the forest with a notepad. Felix, Emile, Armand, Jean and Paul all asked me separately to teach them, please, what I know about the forest, about frogs, and about the process of scientific discovery. The work that I do is particularly well suited to what ecotourists like to hear. Tiny, beautiful, social frogs who fight and court with such frequency that a tourist with an hour to spend, if taken to the right place, and weather permitting, would be likely to see a social interaction. Armed with the full narrative, the guides could try to find for their tourists some of the other players that round out this story—perhaps a Plethodontohyla notostica father frog taking care of his young in a well once used by Mantella laevigata, or the parasite that eats frog eggs.

The fact that the guides had both a passion for the forest and the wit to understand it seemed extraordinary, but it makes sense that such motivated, savvy people should be naturalist guides. Doesn’t it also make sense, though, that the people hired to protect the forest should have passion and wit enough to comprehend and care for the forest? Why this disconnect, where a connection is most critical?

Lebon and Fortune were slipping further into inaction, and with the bit of entropy they added to the system, camp actually fell into disrepair faster when they were around. Twice more they broke the pipe connection to the shower, and left it there, spilling hundreds of gallons of water into camp, until Bret or I fixed it. One morning a group of sailors invaded my small research area, leaving a pile of fresh human shit before I arrived, and attacking me verbally once I was there. I asked them to stay outside the boundaries of my bamboo stand, which I had demarcated in bright flagging tape, and they just laughed. When I reported the incident to Lebon and Fortune, they told me, as they had before, that the beach is not protected.

“It is protected, and besides, my stand is not on the beach, it’s in the forest,” I objected. It was futile. There would be no conservation from the conservation agents that day.

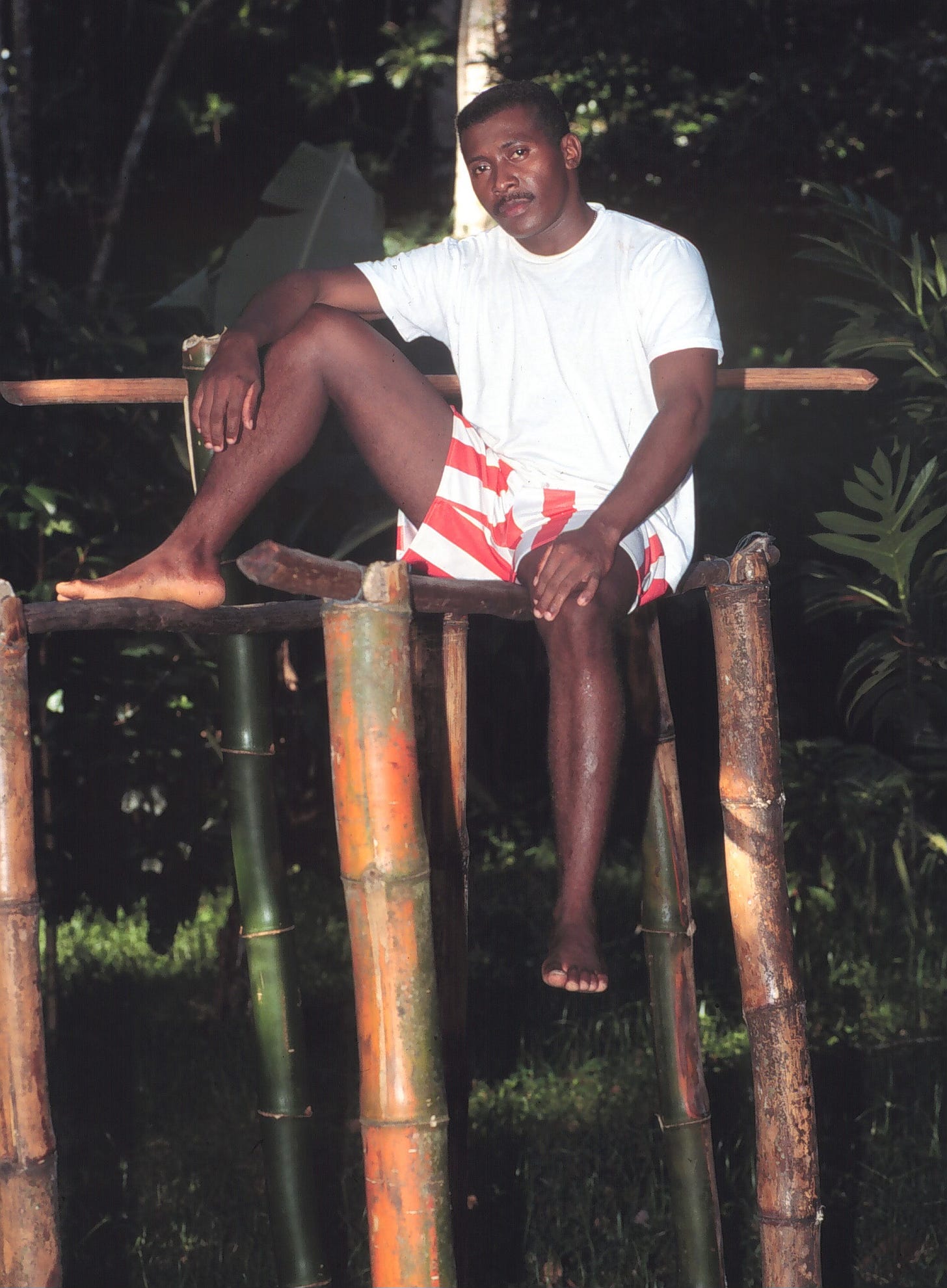

Towards the end of that final field season, the conservation agents were replaced, in stages. First Lucien arrived. He was a hard-working, slight man with a perpetual smile on his face, who cleaned camp daily and walked the coastal trail, clearing the path and making his presence known to any unpermitted Malagasy who might come ashore. Two weeks later Lucien left for a few days to be with his family in town, and was replaced by two brothers, Joe and Vincent. The first thing Joe and Vincent did on arrival was to build gym equipment out of bamboo. A chin-up bar and parallel bars were sturdily erected in camp, so that Vincent might continue his passion for exercise while on Nosy Mangabe. The two brothers were indefatigable. After constructing their bamboo gym, they insisted on cleaning the spiders out of the lab. Besides not being their job, it was a losing battle. They cleared a treefall that had been blocking a path for at least three months, perhaps longer. They actively watched for boats and, when three of them had to moor in our little bay during a storm, they made sure that the sailors only came on land to get drinking water.

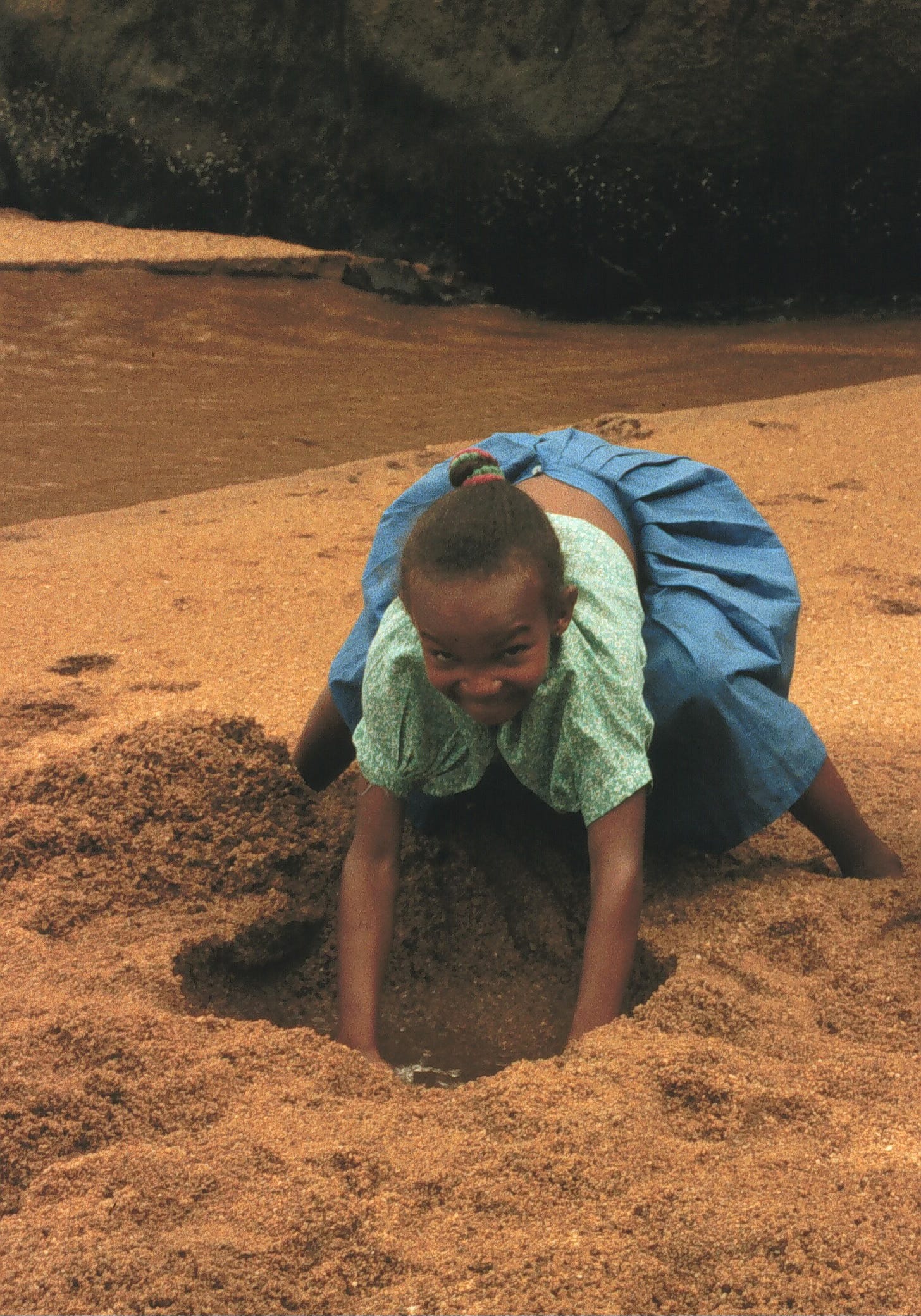

When Lucien returned, he brought his family. His sweet, terrified wife couldn’t make eye contact with the vazaha. His four exuberant children couldn’t help but. The oldest, a lithe, long-limbed boy of 9 or 10, was honing his skills at retrieving mangos from trees. The two girls, the middle children, liked to stand on the dock and watch the waves, or dig in the sand for crabs to fish with. The littlest, but a toddler, was everyone’s responsibility, and his siblings took just as keen an interest in his well-being as did his parents. I asked Lucien if he would allow me to take pictures of his family, both for me and for them, and he was pleased at the request. His wife was too timid to come out of hiding, but the children, who vaguely understood what a camera did, but had not seen one previously, were natural hams. Maybe, I thought, if Lebon and Fortune had been encouraged to bring their families out to the island, they would have been more content, and therefore more productive, during their time there. Although I only saw the first four weeks of the new agents at work, their work ethics and personalities boded well for the future of Nosy Mangabe.

There is one trash can on Nosy Mangabe, half an old oil drum. It is not particularly large—about twice the size of an under-sink kitchen garbage can. A programme exists for its regular pickup and emptying in town and return, but it is not adhered to. Probably, when there are no vazaha on the island, the trash can fills so slowly that it seems ludicrous to those who would be doing the work to cart a quarter- or third- full trash can into town twice a month.

When Bret, Glenn and I arrived, the situation quickly became dire. We almost doubled the population of the island. But it was not our numbers that made the difference. Had three Malagasy researchers arrived—as, indeed, the two pig researchers did shortly before us—trash accumulation would have accelerated, but not by much. The Malagasy eat rice, smoke fish and cigarettes, and reuse every made or found object. As Westerners, we are consumers. This despite our personal environmentalism which translates, in the U.S., to buying in bulk, thus reducing consumption of packaging; recycling papers and glass; reusing boxes and shopping with baskets or cloth bags. But these efforts are, by comparison with a simpler way of life, trivial.

We arrived on Nosy Mangabe with many baskets of rice, which would have comprised most of our purchases for the next four months had we been Malagasy. But the increased options in Maroantsetra meant that there was pasta to be had, imported “Marie 22” crackers, tomato paste, soy sauce, mustard. There was even soy oil, prepackaged in plastic bottles. Previously, the only cooking oil available was coconut oil in dirty oil drums, with flies resting on the surface. An old ladle was used to dip into the drum and deposit some of the opaque oil, sediment and all, into a container you brought. We preferred the stuff that came with its own clean plastic skin, easily tossed when the contents were used.

We bought clothes-cleaning soap, which came in individual plastic packets, to augment the biodegradable CampSuds we had brought from home. We also found person-cleaning soap, a new kind that didn’t stick to your skin for days after each use, as was true of the only soap you used to be able to buy in Madagascar—Nosysoap. It means “island soap.” Nosy soap is still used by the locals for cleaning their dishes and clothes and selves. It is sold as bars without wrapping, open to the air, and is cheap. The new soap, which our Western sensibilities prefer, because it comes off when we rinse, has a nicely comforting name—Lux—and comes well-packaged, in several layers of paper, with plastic on the outside, and a picture of a beautiful, smiling, and immaculate white woman. We believe that we prefer it only because it does not leave the sticky residue that Nosy soap always does, but perhaps the name and packaging also attract some deep-seated consumer in us. Perhaps it is precisely when I am sure that I am not the target audience for an advertisement that they have gotten into my head.

We buy more of these products every time we go into town. The Malagasy don’t tend to—both because they cannot afford it, and because it is not what they are used to. Rice comes without packaging in Madagascar. The diversity we expect in our diets requires that a great deal of food be moved around the planet, and with that food, its packaging. Our desires brought packaging to Nosy Mangabe. Packaging is just trash, an earlier life stage. We filled the trash can quickly.

To alleviate some of the trash problem, and to satisfy our composting urges, we suggested that a pit be dug, for organic trash. At first glance, it seemed extremely odd that this had not been done before—wasn't composting a natural outgrowth of farming on poor soils such as these, a way to recycle what nutrients you could? Our suggestion was taken, and we watched with interest as the pit began to fill with uneaten rice, fruit peels, fish bones and heads. The trash can, now devoted to non-organic material, remained empty. The Malagasy generated essentially no inorganic trash.

We drank perhaps a bottle of wine a week, and the empty bottles were of value to the Malagasy. They do not typically drink wine. The Lazan'i Betsileo vintage, made in the Fianar region of Madagascar, is not a fine wine, but drinkable, and a bargain at $3/bottle. Who here can afford a $3 bottle of wine, when they can get toka gasy—the local, extremely strong rotgut—for pennies? They understand neither our penchant for wine, nor our willful indifference to the glass bottles that hold the wine. To contain the coconut oil they buy in bulk, a wine bottle does nicely.

The trash can never remained empty for long, as we dumped our inorganic trash into the trash can, and filled it. We generated plastic bottles with soy oil residue in them. And tomato paste cans. And the plastic wrappings from pasta, candles, malaria pills.

When you buy prepared food from street vendors in town—samosas, or macaroons—it is handed to you on a piece of old paper. The paper tends to be from a long-since irrelevant bureaucratic document in French, delineating the hierarchy of now-extinct personages in a particular government ministry. Everything is reused until it is gone. We take those greasy pieces of paper and throw them away.

When we bought bouillon cubes in one store, they gave us a plastic bag to hold them. The bag was printed in Chinese, advertising tea strainers from a remote province in China. How many hands must it have passed through before reaching ours? Its journey ended with us. Once emptied of jumbo cubes, we threw it away. In a land of practically nothing, we still managed to generate trash—a tiny amount by American standards, but huge by those of the rest of the world.

The trash can on Nosy Mangabe overflowed with vazaha trash. I left our friends anything they found useful, but still the trash can overflowed. Ten years from now, one may still be able to find a plastic bag from K-Mart or REI in Maroantsetra. As I happily roam farmer’s markets in the States with my Maroantsetra-bought baskets, feeling virtuous, the rest of the world is sorting through my trash, making it valuable.

Next week: Chapter 23 – Cinema Maroantsetra

Love, love, love this chapter.

1. I love the photos, seeing the people I'm reading about.

2. I love this sentence: "Pirates, a Dutch hospital, a Malagasy cemetery, Malagasy fisher people—all of these are part of this island's history..."

3. I love this paragraph:

"The trash can on Nosy Mangabe overflowed with vazaha trash. I left our friends anything they found useful, but still the trash can overflowed. Ten years from now, one may still be able to find a plastic bag from K-Mart or REI in Maroantsetra. As I happily roam farmer’s markets in the States with my Maroantsetra-bought baskets, feeling virtuous, the rest of the world is sorting through my trash, making it valuable."

And I'm musing over the beginning as it struck a place in my memory of a World Civ I took where we discussed how to progress without losing. How easy it is for the developed world to tell the third world as it was called that they cannot.