Antipode is a true account of my experiences while doing research in Madagascar from 1993 – 1999; it was published by St. Martin’s Press in 2001. Here is where we started—with the Introduction. And here are all of the chapters posted thus far.

I was tattooing frogs in camp when, fifty yards away, a treefall almost killed Bret. First there was just noise, a thunderous, splintering collapse of a massive old tree, breaking the expectations of daytime rainforest sounds. Chattering lemurs, frogs calling back and forth, and the drone of the nearby waterfall were instantly replaced with a searing, urgent crack.

Sitting on our tent platform, Bret heard it too. Having worked long nights in neotropical forests chasing down bats, he knew well the distinct snap of a treefall. He looked behind him to see improbable movement, a trunk three feet wide bearing down on him. He sprang. Ran full speed off the platform towards the coast, diving onto the shaky wooden dock just as the crashing stopped, as suddenly as it had begun.

The lemurs resumed their conversation, the frogs their vocal competition, and the lazy heat of the rainforest pressed in from all sides. All seemed normal. Except that my husband was lying face down on the dock, bleeding somewhat but not flattened, and a large tree hung, poised, over our tent platform, caught in the arms of another tree. On a horizontal branch, the tree nearest our platform held the fallen giant. The downed tree’s huge root mass was almost perpendicular to the earth where it had once stood, and an immense mass of wood was suspended over our delicate backpacking tent. Those few hollow aluminum poles strung with nylon mesh couldn’t protect us now. At any moment, the tree might complete its path of destruction to the ground, flattening all in its path.

Somehow, despite the excitement, Glenn and I remembered to put newly tattooed frog T4 back into a Ziploc bag before racing to the scene. Augustin, the naturalist guide, was on the island that day with two eastern European tourists, as were Vonjy and Rafidy. Lebon and Fortune rounded out our population. It was a very full house. After Bret picked himself up and assessed his damage—not bad—we turned our attention to the tree. Here we had a problem.

“What we must do,” announced Augustin, “is go into town, acquire a team of men and a lot of good rope, and…” he trailed off. Bret, Glenn, and I were looking at him in disbelief. After the last few months in Madagascar, we knew without a second thought that what he proposed was impossible. His instinct was surprisingly Western—get the experts, and the proper equipment, to solve the problem. But the suggestion was meaningless in Madagascar. Augustin, a native Malagasy who had been there all of his life, a smart man with a quick wit, surely knew his country better than this.

“Strong rope, Augustin?” I asked.

He smiled shyly and looked down at his feet. “They must use good rope to pull boats,” he suggested.

“Have you ever seen good rope here?” Bret asked.

“No, but…” Augustin trailed off.

“Where could we get strong rope?” Bret wondered aloud, gently mocking. “Nairobi might be our best bet,” he added, bringing home the point to the ever optimistic Augustin. Nairobi, of course, is in Kenya, on Africa, a different country, a different world. Strong rope couldn’t be found on Madagascar. Certainly not in town, a boat ride away, almost certainly not in Tana, a boat ride and plane ride away, with no planes due for several days. We had at our disposal only what northeastern Madagascar could offer, which mostly amounted to brain power and a lot of rice. The tent platform had to be saved, solely with our ingenuity and strength. We had nowhere else to sleep, as the wet season was in full swing, making the ground spongy with water in places. More to the point, backpacking tents aren’t made to withstand months of punishing tropical rains and persistent humidity unshielded. Already my tent was rotting, the grommets ripping, another tent pole snapping spontaneously every week. And this was on the platform, on a small raised bed of wood, with a thatched roof high overhead, and a massive blue tarp we had strung along one wall, to reduce the impact of the weather.

Thankfully, on this trip, Bret was with me. He appears to overpack for every situation, a trait I have often resented when we are simply trying to get from A to B, and it seems unnecessary to drag the stuff of our lives along with us. In fact, he is careful, calculated, and largely efficient in what he packs, and even the few apparently frivolous items turn out to have use in unlikely situations. Such as the 50 foot length of climbing rope he had dragged with us to Madagascar.

Three months earlier, when our living room floor had disappeared under piles of gear, research equipment, scant clothes, toilet paper—all the necessities for life in this endeavor—I demanded of him what on Earth the climbing rope was for. He wasn’t sure. I was feeling peevish, wondering how I could possibly get all of the equipment I needed to conduct my research, including a 50 pound battery, into the 3-bag, 210-pound limit I was up against. Bret didn’t have the same needs—he was coming to help me keep my sanity, give me some field assistance, and write his own dissertation, none of which took up room in the backpacks. So his own 140 pounds of gear and clothes ended up including items such as a snorkel, and a length of climbing rope. At the time I thought him hopeless.

When we had gotten to my site and set up camp, Bret promptly found a use for the rope. He slung it over his shoulder, climbed a large mango tree overhanging the water, and made us a rope swing. It was one of very few distractions in a life otherwise full of field work and the arduous tasks of feeding ourselves and trying to keep clean and healthy. Most nights, as the sun set over the bay and the mainland of Madagascar, we took turns hurling ourselves on that rope swing, twisting in the slight breeze, escaping momentarily the slow, normal confines of gravity and human muscle that we were otherwise restricted to on this island.

Now that a tree threatened to destroy our home—that little tent platform on which we slept, hung our clothes to keep them from molding, and sat at night talking—the rope became a necessity. It was, we had been telling each other, the best rope in all of Madagascar. Augustin had been right—this was what we needed, and it just so happened that we owned the object in question. Now all we needed were experts.

First things first: get all our stuff off the tent platform. At any moment, the tree could break through the branch it was resting on and crush the platform. We went back to the base of the fallen tree and touched it, gingerly at first. Would another fifteen pounds of pressure send it crashing to the ground, or would it take a thousand? We couldn’t budge it, so quickly set to vacating the platform, bundling our clothes, tent and sleeping gear into bags and whisking them away from danger.

“You are all ready. No more danger,” Lebon announced. Now that our stuff lay in a pile in the middle of camp, he figured the job was done.

“No, no, we need to try to save the platform,” Bret reminded him. Lebon looked a bit put upon.

“But the team of men…” he began. He knew there would never be a team of men. Teams of men never just materialize in Madagascar, and when you try to assemble such a group, it might take weeks, months, or simply fail to happen at all. Lebon knew this. But he obviously didn’t want to have a part in deciding what our next move was.

Bret climbed the mango tree on which the rope swing hung, and untied it. He then ascended a tree near the platform, near the tree on which the fallen giant was resting. He tied the rope to the trunk, and tossed the rest down to Augustin, who had volunteered for the truly dangerous task ahead. With great hesitation, and the knowledge that any moment the tree could come crashing down, killing him instantly, Augustin climbed the roof of the tent platform, slipping often on the wet thatched roof. Slowly, with many missteps along the way, and unhelpful instructions from those of us on the ground, Augustin tied the rope to the fallen tree. Bret then climbed another tree, far in back of the tent platform, and tied the free end of the rope to it.

Both of them dismounted, and strolled over to us.

“Here is the plan,” Augustin announced. “We will cut the tree in increments, and every time we cut a piece out of the bottom, it will fall a little, supported by the rope so it does not fall all the way.” He pointed back to the tree Bret had tied the rope to by way of explanation. “Finally, it will swing around and fall away from the tent platform.” We rated the probable success of this plan at about 40%. But we didn’t have a better one. If we destroyed the tent platform while trying to save it, we weren’t any worse off—we couldn’t sleep on it until the danger was gone, so something had to be done.

“Okay then,” we agreed to the plan. Having worked for some years in Central America, where machetes are the cutting implement of choice, I assumed we would use my machete to cut the tree. I had brought it from home, though originally I had gotten it in Costa Rica, where it was indispensable in getting through thick, viney forest. Here in Madagascar the vines weren’t nearly so bad, and the machete spent most of its days alone, hanging from a nail. Bret retrieved it now, and received dubious stares from Lebon and Augustin.

“What’s that for?” Augustin asked. Bret was mildly exasperated. Hadn’t Augustin just explained this very plan?

“To cut the tree,” Bret said. Lebon shook his head pensively, a sure sign that he thought we were making a huge mistake.

“Why not use an axe?” Augustin asked. Another apparently brilliant but misguided suggestion, as we figured there weren’t any axes for hundreds of miles either. The machete would work, even if an axe would work better, but the point seemed moot.

“Where will we get an axe?” Bret decided to play along.

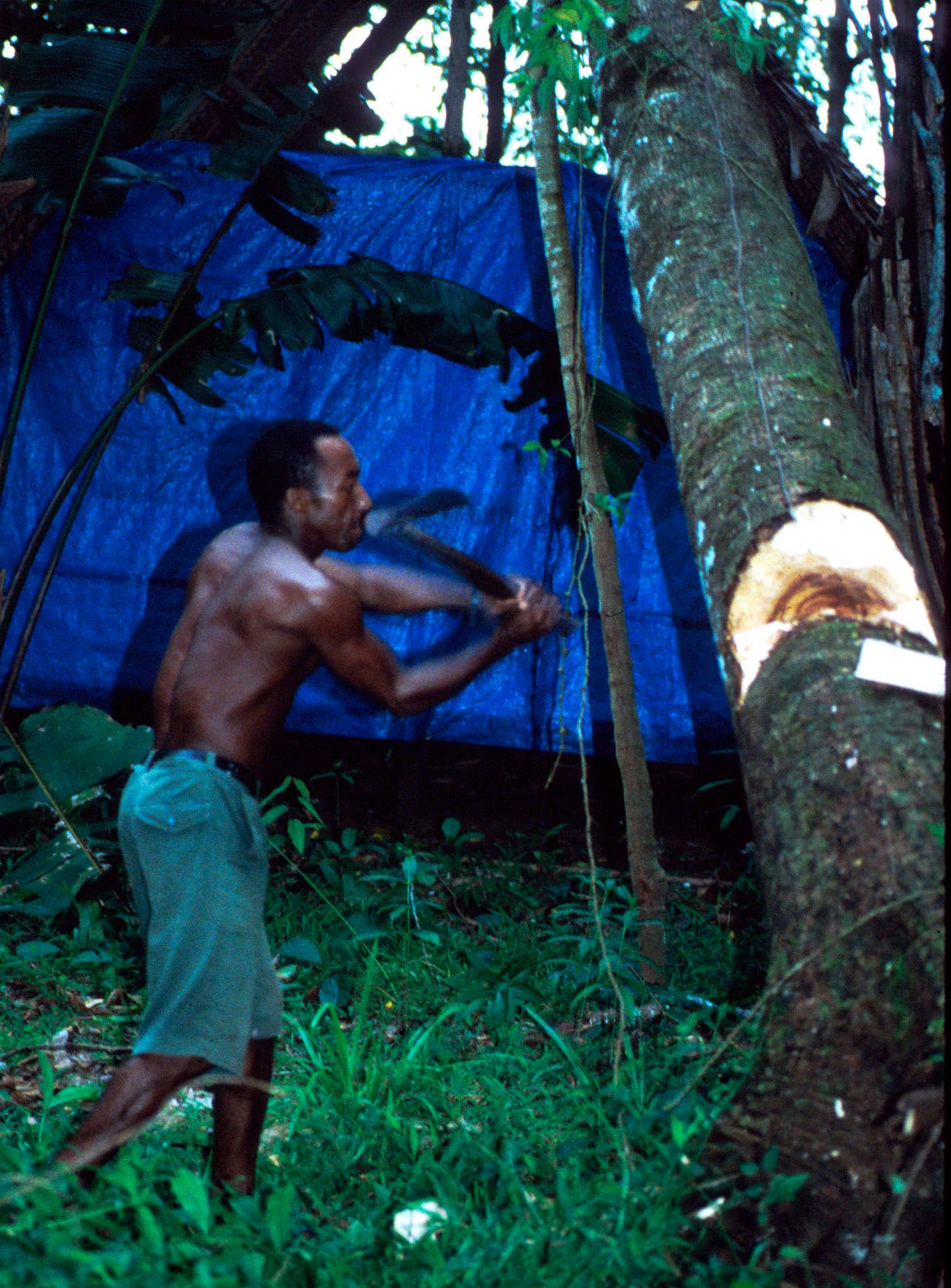

“Right here,” and Lebon pulled an axe from out of thin air, or so it seemed. Bret and I looked at each other, baffled. It was pointless to wonder where this axe had been for the last several months. We had never seen it before. This was apparently the instrument Lebon used to chop wood for the fires he and Fortune cooked over, and it was the better tool for the present job. The head of the axe was none too secure, but it was relatively sharp, and it quickly became clear that Lebon had extensive practice chopping wood. The rest of us stayed out of the path the axe-head would take when it flew off the handle, as we assumed it must, and watched in some awe as Lebon took on the tree. This man, usually quiet and inactive, was remarkably strong, able, and precise, repeatedly whacking away at the same spot on the hard wood of the tree. Augustin spelled him periodically, and Bret tried his hand at it, but the rest of us sat back and watched. Lebon was the star. Tropical hardwoods have the reputation of being impermeable for a reason. They resist heartily the advances of burrowing pests, fungus, and even the sharp blade of an axe.

Soon it began to rain. The axe began slipping from Lebon’s grasp as he attacked the tree, and we decided to call the project off for the day. We moved our pile of belongings into the lab. The lab, remember, is a building of about 12 feet by 36, with a cement floor and porous walls, four windows with no or failing shutters on them, and a door that doesn’t close all the way. The roof leaks, water seeps up through the floor, it is perpetually dark and moldy, and all variety of animals break in when we store items of interest in it, such as bananas, or chocolate. On the stoop of the lab, at one end, we had built a small lean-to out of bamboo and palm leaves, and under this we cooked our rice twice a day.

Still, it was a shelter, the only building we had access to on Nosy Mangabe, a place that was more water-resistant than anyplace else on the island, save perhaps the cemetery cave. Vonjy and Rafidy had set up their small tents in the lab. The Malagasy, as a rule, don’t like the forest, and particularly don’t like to sleep in it. Even these men, who spent their days in the forest chasing down wild pigs, didn’t want to sleep outside on a tent platform. They preferred sleeping in the lab, which was fine by us, for it meant we had our own tent platform. Until today. The “lab” was kitchen to all of us, the pantry where we hung our provisions, home to Vonjy and Rafidy, and storage place for my research equipment. We sat there some days when the rain poured down and there was no point going out into the field, as there would be no frogs. At night, by candlelight, I might sit at the table and write letters. As night began to fall on this wet gray day, our tent platform still had a massive tree hanging over it, so the lab became our home as well. We set up our tent in the lab which, in combination with Vonjy and Rafidy’ two tents and the accumulated gear, pretty much filled it up. There was barely room to get in and out of the tents.

I was miserable. Sleeping in a tent inside a rotting building, where rats come out at night and the air is stifling, ten degrees hotter even than the tropical air just outside, is not my idea of a good time. Just one night of this drove me to frustrated distraction, and I plotted how to escape the confines of the lab and regain the fresh air and privacy of our platform. If it was destroyed, as was likely, we needed an alternate plan, for sleeping in our tent in the lab for the rest of the field season was not a viable option.

Every morning just before dawn I was up to go watch frogs. The morning after the tree fall I woke, confused, wondering why my clock told me it was 4:55 am, but there wasn’t a hint of light yet. Slowly the day before came back—the deafening crash, the endangered tent platform, sleeping in the lab. I got up and out, surveyed the damage again, and decided that I would add little or nothing by standing around observing the progress made on the tree this morning. I decided to go into the field as usual, hoping that I would return, midday, to find a reprieve, and not disaster.

Around 10:30 that morning, I heard a crash, then whoops of yelling from the direction of camp. I was half a mile away, too far to discern meaning from the yells—were they triumphant, or despondent? I sat watching my focal frog do nothing in particular for a few more minutes, before becoming so impatient to know what had happened at camp that I packed up and went back. As you come into camp from the south, on the coastal trail, the first thing you see is our tent platform. This day, as I rounded the corner into camp, I came upon exactly the same scene I’d been returning to for months. Our tent platform. Still standing. Looking up, I saw no uprooted tree leaning precariously over the platform. I dropped my backpack and ran around the back of the platform, where I found Lebon, Augustin, and Bret standing, looking dazed.

“Great job, men!” I enthused. I couldn’t have been happier. That tent platform, which only 24 hours before had seemed stifling and small, representing all of the limits of life on this remote island, now evoked feelings of home, of privacy and comfort, of cool breezes off the bay and limitless opportunity. The area in back of the tent platform, which had once been scrubby secondary forest, was now flattened, the low vegetation having succumbed when the tree bore down on it. Apparently, the plan had worked. When the tree finally came down, after four sections had been cut from it, it had swung within inches of the platform before landing just feet away.

This was cause for celebration. Our home had been saved, disaster averted, and no team of men had been called in. With our own in-house team of men and bring-your-own-rope plan, the tree fall was a thing of the past. How to celebrate?

Had we been home, we might have gone out for a good dinner, indulged in some fine wine, had some friends over, seen a movie. Had we been home, though, we wouldn’t have had to fix the problem ourselves—indeed, it would have been a mistake to try. Living in the developed world, with its insurance policies and experts around every corner, means living with liability. Caution is imperative, and fixing your own problems is frowned upon. If a tree had fallen over our house in Ann Arbor, and been caught in the arms of another tree just overhead, the extent of our response would have been to use the phone to call the appropriate people into action.

The irony is this: in the States, there is less opportunity to really solve your own problems, but far greater means to celebrate your victories, even when the victories aren’t really yours. In Madagascar, particularly on this little island reserve, where our victories were real and in the moment, the opportunity to celebrate was extremely limited. We made ourselves some rice and beans, and broke out one of our cherished boxes of cookies for dessert. The forest spilled out onto the coarse sand beach, turning a rich, saturated green elicited by the setting sun, while needlefish swam in a small school in the shallow water, lazily. We sat on the dock, Bret, Glenn and I, while the sun set across the bay, over Madagascar, relishing luscious, rare European cookies. Knowing that I was going back to my tent platform to sleep that night, all felt right with the world.

Next week: Chapter 22 – But They Are Wild

I loved the experience of “being there” while reading this chapter. Thank you.