Antipode is a true account of my experiences while doing research in Madagascar from 1993 – 1999; it was published by St. Martin’s Press in 2001. Here is where we started—with the Introduction. And here are all of the chapters posted thus far.

The next morning Jessica and I rose at 5:30. Air Mad sent a vehicle to take us to the airport, and we spent an hour or so driving around town, occasionally picking up an additional passenger, mostly stopping so that the driver could chat with passing acquaintances and argue over the price of peanuts. Finally we were deposited at the Maroantsetra airport, the single room that still had no doors. There were flights to and from Maroantsetra twice a week, and when the tiny Twin Otter planes landed, and shortly took off again, people from the surrounding villages came out to watch. Air travel is rare throughout Madagascar—so rare, in fact, that in the south, where graves of important men are usually decorated with zebu horns, a patriarch who had once during his life taken a flight has a large replica of a plane atop his grave. Even before the plane arrived, there was an air of expectation and activity in the airport on flight days, so that though there were at most 20 passengers flying on any given day, there was bustle and excitement at the decrepit airport.

When we arrived, a mass of people swarmed around the large scale. There was no one behind the counter. We dumped our bags in a pile as close to the scale as possible, then arranged our tickets in a decorative fan shape on the counter next to the others, similarly prepared. Sitting down in the plastic chairs that were surprisingly reminiscent of airports in the Midwestern United States, we began to wait.

On this day, the other travelers included a couple of would-be courtesans, a bit past their prime, dressed in black lace and external red bras, coiffed and made up and bedecked in gold necklaces and thick gold bracelets, but a little older and heavier than most of the women you see consorting with tourists and expats. There were two young Frenchmen we hadn’t seen before, probably short-term tourists. They were the only other vazaha. Several people carried large baskets, sewn up at the top so as not to spill their precious contents. Although it is a very select group of people who travel by air in Madagascar, it’s still not unusual to get on a plane in which sewn-up baskets are used as luggage.

One man had a massive white block that crumbled at the edges, probably salt. Another carried gnarled pieces of driftwood. A third ported an immense cardboard box filled with coral. Most of the women over 40—many of whom were not flying, just observing—wore two straw hats at the same time, stacked so neatly one on top of each other that you had to look very closely to perceive that there were, in fact, two hats there. Some wore five or six—an efficient, if peculiar, way to transport them.

A well-dressed, gray haired man who, by his bearing, portrayed his supremacy in the Maroantsetra airport’s social and political hierarchy, began making the rounds. He bore bad news. This was not unexpected, given that our plane, which was supposed to leave in less than an hour, was not yet in evidence.

“I am quite sorry, but the plane will not arrive until 11:20 this morning,” he apologized. The level of precision made a further mockery of Air Mad—he might as well have said it would arrive at 11:23, for in the four hours between now and then, anything could happen. “Would you like to return to town?” he asked. The Frenchmen and slinky young women, as well as the proprietors of the various marine art, were all going back to town. We chose to avoid dragging our heavy equipment through those dusty streets one more time, and stayed at the airport, far removed down a ruined dirt road even from the relative bustle of Maroantsetra.

To occupy herself, Jessica took a walk. She reported later that she had been wandering down a footpath near a small village, and had been surprised to hear an old woman, standing behind a rickety fence, speaking in French to her.

“The raging bull coming up behind you is in some danger of goring you,” the woman advised. Jumping nimbly aside, Jessica thanked the old crone, then paused to watch the agitated antics of this beast, as it pulled the man who was trying to calm it. Softly, a new voice arose at her side.

“Bonjour vazaha,” it said. Jessica looked askance, and pretended not to hear this too-typical introduction. The man was persistent, though, and finally she muttered “Bonjour” in reply. He took this as encouragement, and embarked on the story of the bull’s fate.

“This bull will be sacrificed today, for a celebration of the turning of the bones of the ancestors.” This got Jessica’s attention. One of the most renowned and fascinating cultural traditions of many of the Malagasy tribes is the ritual retournement. In the animist tradition of ancestor worship, the bodies of the ancestors are dug up every few years, dressed in new shrouds and, if they are fully decomposed, moved from the “body boxes” they were buried in to smaller, stone “bone boxes”. Even after the remains are in bone boxes, the tradition continues, and the ancestors receive new shrouds on a regular basis. While the ancestors are above ground, the current village elders speak to them, recounting the events of the previous years.

“Isn’t this the wrong season for the turning of the bones?” Jessica asked.

“No, no, this is the right time, for it is in accordance with the rice harvest.” He embarked on a detailed, hard-to-follow explanation of the importance of the rice and the ancestors being in harmony. Then he added, “you may come to the ceremony if you would like, and participate with me and my family. If you bring a camera, that would be wonderful, for we have never had photographs before.” Enthusiastically, Jessica told him that she had a friend with a camera, and that we would return shortly.

Having hurriedly gathered my camera equipment at Jessica’s retelling of her interaction, I returned with her to the site where the frenzied bull had almost taken her out. We found nobody. I wondered briefly if we hadn’t been conned, realizing that right now our bags were sitting unguarded in the middle of the mostly empty airport, and could easily be taken. Despite my earlier experience with the clove boat guardian, I generally had little suspicion of the Malagasy, finding them far less likely to steal than their need might predict. I didn’t want that impression to change.

We turned and walked down a side road, and shortly came upon a crowd. Several women wearing bright, matching lambdas, the traditional fabric skirt wrap, were disappearing behind some thatched-roof houses off to the right. We stood around being vazaha for a few moments, looking vaguely confused, and the trick worked. Out came Knick (pronounced Kuh-nick), the man Jessica had met earlier. He was, it seemed, the master of ceremonies for this retournement, which was now beginning its second day. The village was preparing the zebu for sacrifice, and preparing to listen to the prepared speeches of the elders.

Knick led us in through the crowd and sat us down in front of several layers of men and children. The women had all dispersed. Repeatedly we suggested that perhaps this wasn’t the place for photographs, that we would be honored to sit and watch only, but he insisted, and it became clear that he wanted documentation of the event. I would send or bring copies of these pictures back, and this tiny village would have a permanent record of their sacred ritual.

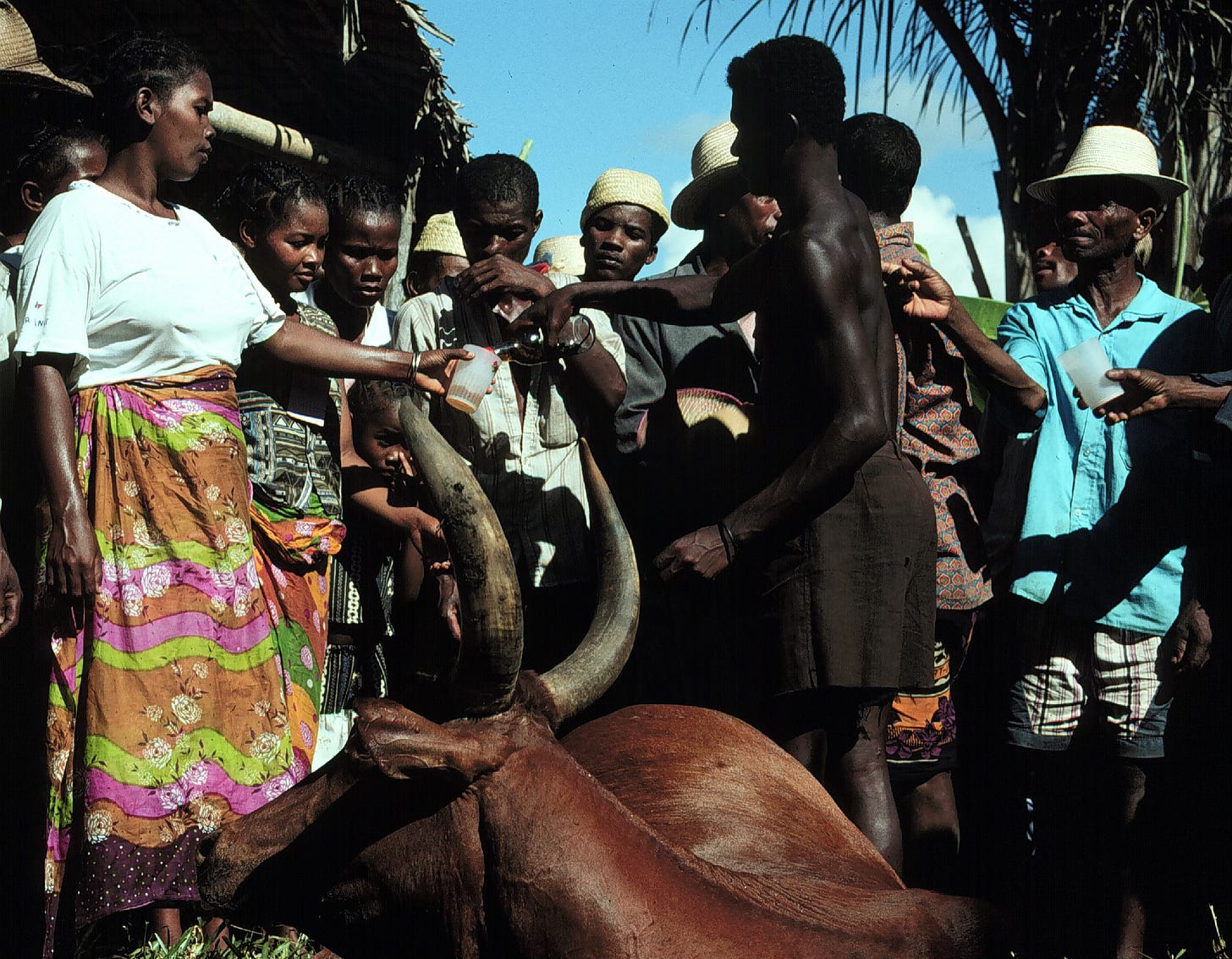

We were in an open area with no trees, the village buildings of thatch and bamboo encircling us widely. In front of us lay the zebu, feet tethered, lying on its side, groaning intermittently. It frequently raised its head enough to look truly menacing, causing the crowd to recoil. In front of the zebu stood a low tray of banana leaves, on which were three glasses of pale liquid, the ceremonial rum. Also, a saucer with clear liquid in it, which was not elucidated to us, though Knick explained most aspects of the goings-on.

An extremely dark young man in a brimless straw hat scurried to and fro, adjusting the angle of this banana leaf, filling that glass just slightly more, looking askance at the zebu when he had to walk near it. He didn’t interact with the other participants, and I asked Knick about him.

“To do the actual killing, a Comoran man is needed. Otherwise, the ancestors are displeased.” He nodded in the man’s direction. “That is the Comoran.” So blood-letting was performed by outsiders. How they had found a Comoran, a native of the Comoros Islands to the north of Madagascar, I had no idea.

It came time for the elders to address the ancestors, to tell them how the villagers had spent the time since last they were above ground. The crowd, perhaps a hundred people, circled around the zebu, and a distinguished gray haired man stood up. His hat in his hands, he spoke clearly and, it seemed, eloquently, though I understood none of the words. Sometimes he drew laughs from the crowd, more rarely brief applause, and as he finished it was clear he had elicited great joy. Then a second man rose, tall and gaunt. The sun was rising in the sky, and shone fiercely down on him. A villager raised a palm leaf over his head to shield him. This man had the air of a stand-up comic. He delivered lines dead pan that drew great laughs. The barest hint of a smile played at the corner of his mouth, as if he had rehearsed for weeks, and was finally getting to orate.

When the elders were finished, a woman poured rum over the zebu, then slapped its stomach. Villagers gathered around and held the zebu’s tail in their collective hands.

“What is the significance of this activity?” I asked Knick, curious.

“It is important for the villagers to hold the zebu’s tail in their hands,” he answered, leaving any further explanation to my imagination. After a few more iterations of pouring rum and holding parts of the zebu, the animal was dragged ten feet away by several men. A little girl with a pale, torn dress walked by, but was indifferent to the proceedings. Bracing himself out of reach of the zebu’s sharp horns, the Comoran slit the animal’s throat while additional men tried to hold it still. The blood was collected in a small vat.

As the sacrifice was happening off to one side, women began dancing, all color and swirl. They danced in a long bending line, following one another. Soon they were singing as well, and clapping their hands as percussion. The sacrifice of the zebu marked the end of the solemn portion of this long ceremony, and the beginning of the celebration. The rum, previously reserved for small ritual-laden sips only, began to flow freely. Banana leaves were ornately folded into cups with long curved sides, as the few available glasses had apparently been reserved for the ancestors. Everyone living drank from banana leaves. Jessica and I were handed leaves containing some of the potent liquid, and it was made clear that we must drink, or risk displeasing the ancestors. One old man, who had apparently been nipping at the rum before the appointed time, danced among the women.

After the Comoran killed the zebu, he beheaded and eviscerated it. A platform of banana leaves was laid out where the speeches had taken place, and proper glasses of rum placed at the corners, for the dead to imbibe. A middle-aged man and woman, who Knick said had been specially chosen for the task, were seated on low wooden stools in front of the display. They were handed umbrellas to shield themselves from the hot sun. Slowly, piece by piece, the head and organs of the zebu were brought and placed on the leaves in front of them.

“These two people must keep watch over the zebu’s organs,” Knick informed us, “and if they protect these parts from evil spirits until midnight tonight, then we are free to feast on the meat.” I glanced in the direction of the organ guardians. The man was eyeing the ritual rum covetously, while the woman shooed away a curious chicken with a palm frond. “Please, if you can, stay with us for our feast.” Knick was a gracious host, but we had been there for two hours, and had a plane to catch. I felt sure that both evil spirits and chickens would be kept at bay, and the feast would commence as planned. Until then, dancing and drinking was the order of the day.

“Before we leave, Knick, might I take a picture with just you and your family?” I asked. He had been so generous, encouraging photos of particular people, but I had not seen him with his own family. He grinned widely.

“Yes, please, I would like that. Wait here—I will go get them.” We stood in the shade of a hut, watching the women dance, their lambdas blinding as they twirled. Several children stood near us, eyeing us curiously.

Folded banana leaves were being passed among the men, who now lounged on the ground, occasionally tipping a leaf too far, spilling its precious contents.

Knick reappeared, and arranged his family in front of the organ display. He had gathered more than 30 people. I had forgotten that family refers to a more inclusive yet more closely-knit unit in Madagascar than it does in America. These were not distant cousins he saw once a year, but the people he lived with and among, on whom he relied for friendship, labor, and advice, and who relied on him.

Returning to the airport after the retournement, we unwittingly played the pied piper, a long line of festive children in tow. I felt a need to record some observations about the retournement, and opened my computer, to the delight of the amassed youngsters. They crowded around so closely—mine was the only computer for hundreds of miles, and surely the first they had seen—that I wished I had tricks or games to show them. But to reduce the risk of incompatibilities and crashes in the field, I had stripped the thing of most of its obvious pleasures. But even a spreadsheet was scintillating to these children, and when I simply typed text, one little boy actually sounded out some of the words he saw. His literacy was stunning, given the poverty he came from, the lack of schools or books, and the fact that I was writing in a language that was, at best, his third, after Malagasy and French.

Finally it was time to be processed for our flight, so we reunited ourselves with the bags we had dropped by the scale, before being called up to the counter. The sequence in which we were called seemed to follow an algorithm that included the order in which the tickets had been laid down, but also incorporated how pleasingly they had been fanned out into their decorative display. Shortly it became clear that the scale was not just for our bags, but also for us, the plane being so small that everything going on board had to be weighed. We were more massive than any of the Malagasy being weighed, and gasps of incredulity could be heard as Jessica, and then I, clambered up on the platform, and the needle flew upward. Apparently we were light enough, though, for soon we were on our way.

We were not going directly to Tana, but to Antalaha, a town on the east coast of the Masoala peninsula. Antalaha is unlike other Malagasy towns in that, though most of its residents are impoverished, a few have become extremely wealthy from exporting vanilla. While even middle class Malagasy such as Rosalie could never conceive of being able to afford a plane ticket out of Madagascar, some of the residents of Antalaha have private jets, with which they fly to Paris for weekend shopping sprees.

The Wildlife Conservation Society had its regional headquarters in Antalaha, and I was to meet Matthew Hatchwell, the head of WCS in Madagascar, with whom I had been in much communication. I was also due to give a short presentation on my research to the WCS staff. We were welcomed into the Hatchwells’ home, which had once been a building used for processing vanilla, and there spent a truly enjoyable, if odd, few days. Just days before I had been living in the rainforest, sustained on rice and fish broth, washing myself and my clothes in a waterfall and sleeping in a molding tent. Now, suddenly, after a brief foray into a traditional Malagasy ceremony, I was having tea with Matthew and his wife, playing with their inquisitive, towheaded son, sleeping in a real bed and eating chocolate chip cookies. I didn’t know how to grapple with so many changes this quickly. Wistfulness for the calm of Nosy Mangabe hit me for brief spells, while I also retained wistfulness for the first world, although our time with the Hatchwells was a good approximation of the comforts I craved.

We flew back to Tana, where Jessica was reunited with her parents and I stayed in their house for the last time. Oasis though their house was, it was yet in Tana, and the ubiquitous fumes, beggars, and curbside food stalls seething with naked children and rats were still in evidence when we moved through the city. Ros had been doing my homework for me, and informed me when we arrived that Air Mad had changed its schedule. My flight to Paris was leaving 32 hours earlier than my ticket suggested, and it was overbooked. As irritating as this glitch was, the Metcalfs, true to form, made everything comfortable during my last day in Madagascar. Jessica and Peter took me on a walk to a hillside outside the city, on which an old tomb lay partially obscured by weeds. This breezy, gorgeous afternoon, clouds high above the hills, rice paddies far below, would be my last image of the vastness of Madagascar, until I returned again.

As I waited in Ivato airport, the international gateway out of Madagascar, I realized that the day I had fantasized about for so long had finally arrived. No more naked sailors. No more sitting on my blue three-legged stool waiting for frogs to act. No more clumped white rice and questionable fish heads.

At last the plane was ready. As I boarded, I felt a different kind of gaze upon me. This was not the “there’s a vazaha in our midst” look I had been receiving all of these months. Now I was back in the land of white people, for even though this was an Air Mad flight out of Madagascar, only the wealthiest Malagasy ever fly out of their country, and most of the passengers were white businessmen, expats, and tourists. What I felt now was their gaze, made curious by circumstance. Many of these men who had been in Madagascar had taken advantage of the slinky Malagasy misses for rent, but few considered such women wife-material, although the women are specifically seeking marriage. These men were returning to their country, to women of their same class and education, for their acknowledged relationships. During their foray into a reversal of mate choice and sexual politics in Madagascar, these men had seen few if any white women. White people are rare in Madagascar; white women are but a tiny fraction of that already small minority. I had been free of mirrors for many months. Now I realized I had also been almost entirely free of the male gaze.

Our nighttime departure from Tana meant that, almost as soon as we took off, Madagascar had disappeared into memory. Only around Tana were there any lights at all. Even where they existed, they were sparse, separated by rice paddies, dimmed by frequent power outages. Fitfully I slept, as we landed in Nairobi, Munich, and finally Paris. I was heading to London, where my parents were living at the time. I knew I would be surrounded with the trappings of the first world that I craved, but I was not prepared for my reaction to being back in a land where I spoke the language; where commerce was constant, fast and efficient; where nature was relegated to parks; where there were so many things available to buy, and eat. Walking down a busy London street, my mother lost me to reverie. Forcing her way back through the crowds, she found me gazing into the window display of a Baby Gap.

“Our children are so pampered,” I began, than looked around at what they grew up expecting—lots of goods, but also heavy doses of anonymity, stress, and urban sprawl. “They have all these material things. But few of them have a family to compare with Knick’s.” We are nuclear, tight in upon ourselves. Looking out at the world from our small cocoons, our narrow vantage points offer little insight into the breadth of possibilities for human life.

Sensing my tension at being dropped into the big city after so much time in the rainforest, my parents took me to the countryside. We visited lovely English ruins, which sat in rolling fields covered in wildflowers. Walking up the spiral stone staircase in the ruin of a castle once lived in by royalty, I realized that I had been in ruins like this as a child, and that it had not occurred to me then to imagine what it implied about people’s lives. It was a ruin, an historical artifact, not something to be interpolated into a modern understanding of human life. But now, the comparison seemed obvious. The very richest and most pampered English of the 14th and 15th century lived surrounded by cold, dark, thick stone walls. Their beds were made of straw. The kitchen staff kept fires burning always, because they were so hard to start. Filth crept in everywhere, and many royals, even, made no attempt to stop it. Bathing was an occasional occurrence. The rich had more trees and woodland animals around them than the average middle class person from any country today. And already the poor had even less, living in urban pits with few laws or public health policies to protect them.

How utterly foreign I am among the Malagasy, just half a planet away. I could barely comprehend their expectations for their lives, there were so few parallels with mine. But move me in time, just 500 years back, and I was equally at a loss. Hearing about the lives of the 15th century British royals, or of famines in North Korea, plague in Africa, abject poverty in America—this is not sufficient to evoke empathy. One must truly see people living in ways other than one’s own. Better yet, one must live differently, with other people’s rules and history, for a while.

So ends Part II

Next week: Part III, Chapter 18 – A New Launch

Never a dull moment in your stories… dazzling!

Thanks for sharing these Heather. I love reading of your experiences but they also make me wistful of the inner anthropologist that never came to be. Is there a particular branch of anthropology- evolutionary anthropology or is it just inherently evolutionary. Your writing is always reminding me to slow down and observe which is so necessary in today’s world!